#image_title

#image_title

After 148 years, nothing left to try to avoid losing money and now a livelihood

When Paul Adams was growing up on the rolling hillsides that comprised his family’s farm just north of the Trempealeau County community of Eleva, similar dairy operations dotted the surrounding countryside like dandelions in springtime.

The young Adams helped milk and feed the cows at his home, putting up hay and mending fences, just like his neighbors. When Adams eventually took over the farm where he had grown up, those neighbors made their living on farms ranging from 120 to several hundred acres, milking herds of 30, 40 or even 50 cows.

“There was a farm family just over the hill there,” Adams, now 68, said from his dairy barn Monday morning, motioning with his hand toward a nearby rise in the snow-covered terrain. “And then down the road there was another, and another across the road. And then there was the Schultz farm just at the edge of town … There were farms all over this area.”

Those days of small family dairy operations appear to be gone, lost amid ever-growing pressures from low milk prices, rising costs, decreased milk demand and the need to operate more efficiently.

On Monday the organic farm Adams and his wife JoAnn have operated for four decades — the land Adams’ ancestors settled 148 years ago after moving from Pennsylvania to farm — became another in a growing list of Wisconsin dairy casualties.

The 600-plus-cow herd was milked one last time, then most of the animals were loaded into semi-truck load after semi-truck load and shipped to Texas, where they will become part of a 3,000-cow dairy operation. The others were sent to slaughter.

Adams recently sold another 400 youngstock, and he will put the farm up for sale. After 40 years of overseeing the farm, he is left to simply hope the property sells for enough money to pay off his debts.

He said his 1,100-acre dairy farm was the among the last in the nearby area, a sign of the demise of the profession that once provided the livelihood for the surrounding region and most of rural Wisconsin.

“There just aren’t many of us left anymore,” he said from an office in the dairy barn where his cows were being milked, then loaded into trucks. “It’s a disappearing way of life.”

The loss of Adams’ farm is part of a growing trend in Wisconsin, where 818 dairy farms — more than two a day — went out of business in 2019, according to the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. That figure was the most in the U.S. and represents 10 percent of the state’s approximately 8,100 dairy farms at the start of last year, a figure that has shrunk to less than 7,300 currently. The state has lost one-third of its dairy farms since 2011.

Dairy farms are struggling nationally as well, as reduced milk demand, too much supply and trade tariffs limiting milk and cheese exports have created a difficult economic climate for dairies. Nationwide, almost 3,000 dairy farms shut down in 2018, a 6.5 percent decrease, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture figures.

Dairy farming difficulties have prompted concern at the state and federal level. During his State of the State address in January, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers called for a special session to address the needs of Wisconsin’s rural areas, including an $8.5 million investment in the ag industry.

Last month Assembly Republicans offered their response.

The bills would give farmers $9 million in tax breaks on agriculture buildings and another $9.5 million to allow sole proprietors, including small family farms, to deduct health insurance costs from income taxes. Those bills received Assembly approval late last month and could be considered by the Senate later this month.

As more dairies continue to disappear from Wisconsin’s landscape, agriculture organizations are trying to address the issue. In a seemingly unlikely move, the more conservative Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation and progressive-leaning Wisconsin Farmers Union partnered last month to discuss how to manage the oversupply of milk. Spokespeople for both organizations said they are working to devise strategies to assist dairy farmers.

As an example, through its Dairy Together initiative, Wisconsin Farmers Union has joined with other groups from across the U.S. to advocate for a dairy growth management plan that would better balance the dairy supply with consumer demand.

According to a study by dairy economists Chuck Nicholson, from Cornell University, and Mark Stephenson, from the University of Wisconsin, such a program would increase average milk price and farm income while reducing price volatility, farm loss, and government expenditures.

“Wisconsin dairy farmers have been struggling under market pressures for too long,” Wisconsin Farmers Union President Darin Von Ruden said. “If we want to pride ourselves on being ‘America’s Dairyland,’ then it is beyond time that we address the volatile prices and market pressures that are putting family farmers out of business.”

Adams said state and federal lawmakers must take action to help dairy farmers in Wisconsin and elsewhere across the U.S. to prevent more farmers like him from being driven out of business. Continued pressure on farmers to grow larger and create economies of scale has only served to keep milk prices low as costs of doing business continue to climb, he said.

“We still call ourselves America’s Dairyland, but we’re really not any more,” Adams said. “We need to completely overhaul the current system. What we’re doing now simply isn’t working.”

Boom, then bust

The loss of Adams’ farm is notable, industry analysts said, not only because it represents another shuttered dairy, but because it illustrates that even farmers adapting to the changing farm economy — even those growing their herds and entering new markets — can’t necessarily stay in business.

In 1994 Adams significantly expanded the farm’s herd and added acreage, and in 2002, seeking a niche market for his milk and a way to farm “in a healthier way for the land, the cows and people,” Adams decided to transform his operation into an organic farm.

He spent countless hours reading any literature he could lay his hands on about how to farm organically. He learned about different ways to feed his cows, different means of managing the soil.

“It was a whole different way of farming,” Adams said of organic methods. “It was a healthier way. Once I decided to do it, I was all in.”

For years Adams’ bottom line improved as the price he received for his milk nearly doubled. His herd grew, and he found demand for his milk. It appeared as if his decision to grow his herd and then switch to organic would allow the farm to continue.

Then, in 2017, the U.S. Department of Agriculture came under control of the Trump Administration and new Secretary Sonny Perdue, with promises to remove regulations to give organic farming a niche in the marketplace.

The administration relaxed federal regulations regarding required grazing for organic operations, allowing farms much larger than Adams to become certified organic. That development would prove pivotal in eventually forcing Adams and other organic dairy operations to struggle and, in some cases, shut down, he and others in the agriculture industry said.

As more factory farms got into the organic industry, the amount of milk increased significantly, driving down price. The milk Adams had been selling at $38 per hundredweight (100 pounds of milk), dropped to $29, a loss of about $3,600 per day. He needed a price of $32 to break even, even after the bank relaxed some terms of his loan, he said.

Facing ongoing loan repayments and continued operating costs amid declining income, Adams looked for other efficiencies. He found cheaper feed byproducts to feed his herd. He worked with bankers to restructure his debt. He hoped for higher milk prices, more demand for his organic product.

Then his loan was sold to another financer, and the payment schedule was upped. Adams and his wife hoped earnestly for a price increase in January, knowing that was necessary to keep their farm afloat.

Instead, they were hit with a gut punch: The price they received for their milk actually dropped, from $29 to $26. Shortly after they lost their long-term milk contract, and for two days in January they sold their milk for just $17 per hundredweight.

A short time later they made the difficult decision to sell their herd and the farm, ending a century-and-a-half of dairy farming on their property.

“Making that decision was hard, real hard,” Adams said Monday of ending the farm. “To work so hard and know in the end you couldn’t make it work, that’s not easy to accept. But there are forces beyond our control, and we couldn’t make enough money to keep going.”

‘Something different’

Even as a youngster, Becky Adams was known as the “farm girl,” her parents said. She always had a special bond with the cows, learning what stressed the animals, what made them calm. Whenever there was a new chore on the farm, whenever there was new machinery to operate, Becky wanted to learn how to do that work.

“She would always tell us ‘You might as well teach me now, because when you’re no longer running the farm, I am going to have to know how to do it,’” Paul Adams said with a smile. “She was always going to run this place.”

Becky has helped operate the farm for years, serving as its herd manager. On Monday she meticulously supervised the tracking of the cows one last time before they were loaded into trucks and shipped off.

During a brief break in her work Becky, 36, described the difficulties of losing the farm, of losing her livelihood, of losing a way of life she had enjoyed, a way of life she wanted for her two young children.

“I’ll really miss the cows,” she said, wiping a tear from her cheek as she discussed the finality of the farm’s end. “I’ll miss interacting with them. They were like pets to me. I’ll miss this work, this lifestyle. I’ll miss all of that.”

Becky and her family will move a half hour north, to the city of Altoona. She isn’t sure what is next.

“We’ll just have to figure it out,” she said.

The end of the Adams farm means the loss of jobs for the 20 workers who provided much of the labor there. Some have already moved on to other jobs, while others are seeking work. Those who have found positions elsewhere have had to uproot their families and relocate, Adams said.

Adams and JoAnn plan to continue to live in the house on a hill that overlooks their farm, including the barn that once housed the dairy herd of Adams’ childhood and younger adult years.

The building stands as a reminder of a different time, a time when Wisconsin was America’s Dairyland, a time when small dairy farmers could make a living.

“So much has changed,” Adams said, gazing out the window of his home at the farmland beyond. “We just keep growing bigger and bigger, and that isn’t working. My situation is proof of that. We need to do something different, or we won’t have any dairy farmers left in Wisconsin.”

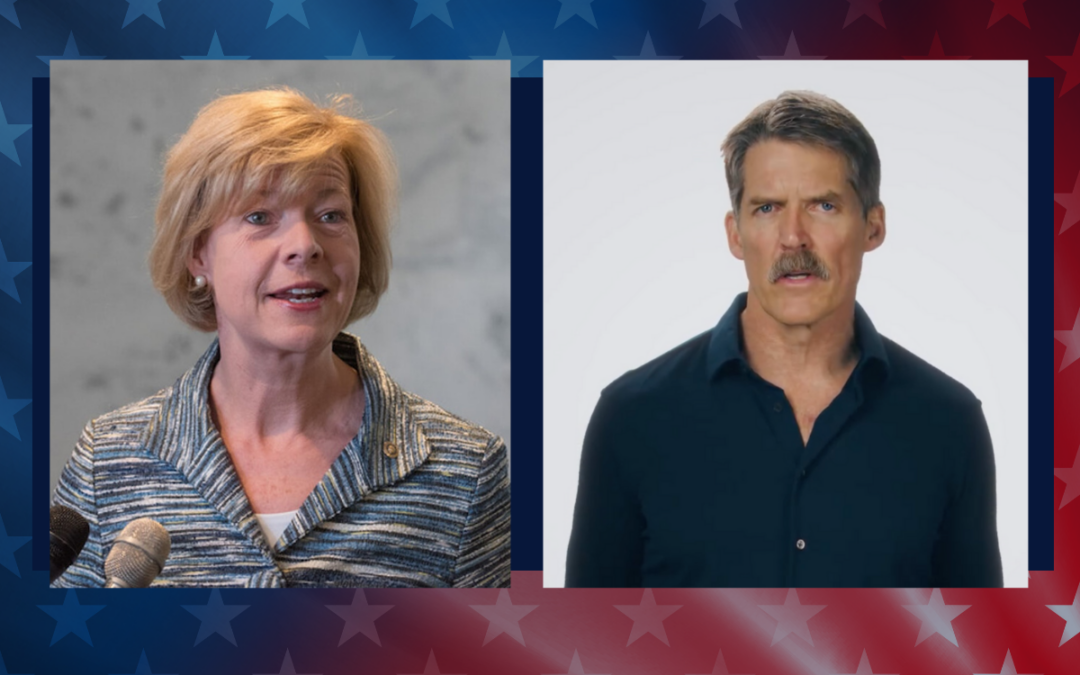

Politics

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Who Is Tammy Baldwin?

Getting to know the contenders for this November’s US Senate election. [Editor’s Note: Part of a series that profiles the candidates and issues in...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...