#image_title

#image_title

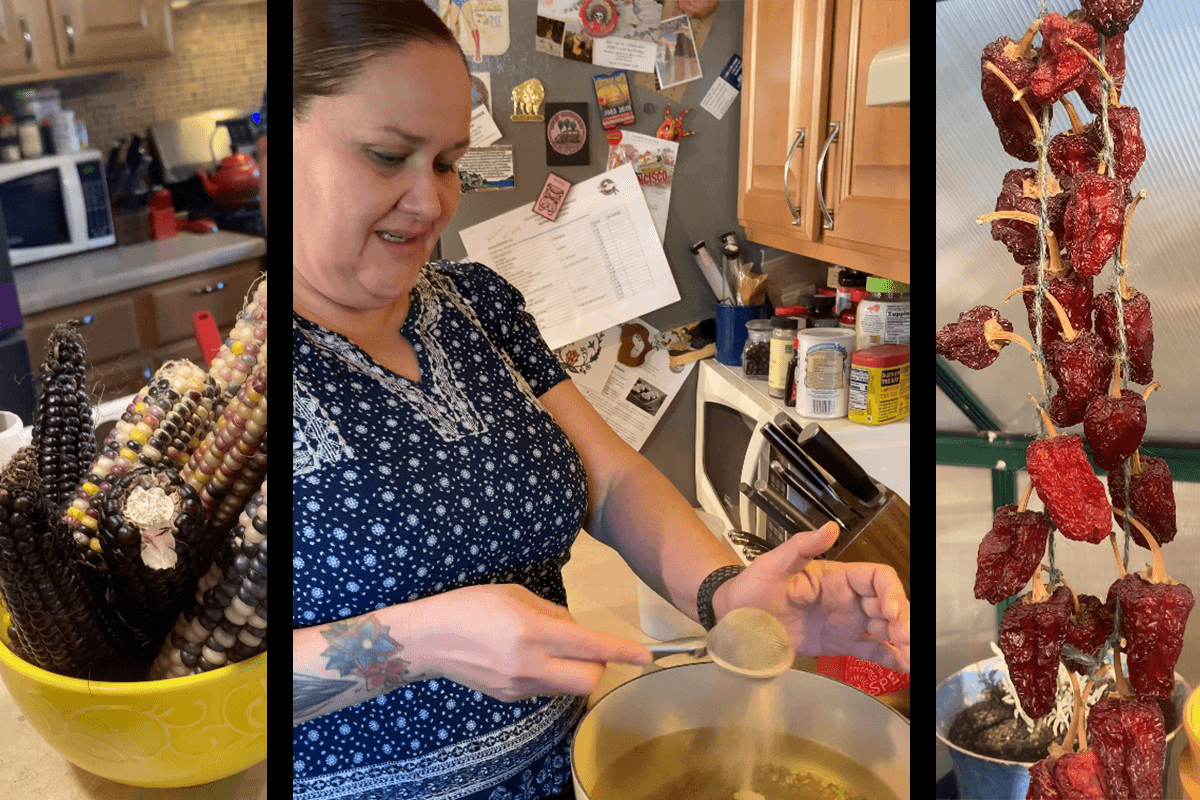

From the Menominee to the Ho-Chunk, Wisconsin tribes are finding new ways to celebrate and preserve their history through traditional food and agricultural practices.

Francisco Alegria is a trained hibachi chef, but when it comes to his favorite foods, they’re closer to home. Alegria grew up on the Menominee tribal lands around Keshena, where ramps, a type of wild onion indigenous to the area, are one of the first edible plants to sprout in the forest in the spring.

“One of my favorite things to do is to go up there with my parents and listen to their stories and harvest some ramps, come home, clean them up, fry them up with a little deer meat or something,” Alegria said. “I cooked all these expensive meals: Lobster, swordfish, Chilean sea bass. But you get me at home in the spring, I would pick ramps and some venison over any of those expensive meals.”

While Alegria grew up eating Menominee foods, foods based in Menominee traditional agricultural, and cultural practices, he never really thought of it as a cuisine. When he was training to be a chef, there were no classes on Indigenous cuisine.

It’s only in the past few years, and due to the work of Indigenous chefs—such as Sean Sherman, a member of the Ogalala Lakota Sioux tribe who opened an Indigenous restaurant in Minneapolis, and Elena Terry, a Ho-Chunk chef who founded Wild Bearies, an organization that promotes Indigenous foods—that their foods are being recognized as a cuisine and as a valuable component of their cultures worth preserving and sharing.

“For as long as I can remember, this food has been an important part of not only our daily lives, in preserving our culture,” Terry said. “I was raised in a very traditional family and I always loved being able to go to ceremonies or places and spaces where foods were celebrated.”

Part of Terry’s work is traveling the country, teaching about Ho-Chunk cuisine and learning from other Indigenous chefs. Indigenous cuisine is as varied and diverse as Indigenous people and their cultures.

“What’s indigenous to this area is completely different from what’s indigenous to Southwest or Alaska,” Terry said. “Celebrating the diversity of that is one of the most beautiful parts of my job.”

Within that diversity, there are some common threads between the tribes and with recent mainstream food trends: Indigenous cuisine tends to be local, seasonal, and sustainable.

Etched in the Earth

In 1995, foresters on Menominee land found strange dimples and ridges in the ground. David Overstreet, an archaeologist who has excavated sites across the state of Wisconsin, was called in and found evidence of Menominee agricultural practices.

This was after centuries of the Menominee being designated as hunter-gatherers by researchers and in government records, although when Overstreet dug into the historical record a little deeper, he found reports going as far back as the 1850s that the Menominee had raised agricultural beds.

Digging into the beds themselves, Overstreet found evidence of a complex agricultural system similar to others seen across North and South America, where Indigenous people planted crops with symbiotic relationships in the same field, a practice that not only provided a diverse nutritious diet but also enriched the soil.

RELATED: Indigenous Farming, Cooking at Center of Bad River Community Garden Program

“Everybody was really enthralled with how complex these agricultural systems appeared to be,” Overstreet said. “It underscores how far off track the historical characterizations of their past food ways, as well as Native American agriculture generally, had been described.”

While evidence of Menominee agriculture was news to Euro-American researchers, for many of the Menominee, it confirmed what they had long known.

“It’s something that we, as Menominee people, knew and understood,” said Rebecca Elder, sustainability coordinator at the College of Menominee Nation in Keshena. “I think that finding these ancient garden beds confirms that what we knew is actually fact, as sometimes Western scientists need to have that proof.”

Relearning Self-reliance

Elder is experimenting with how to grow flint corn, which Overstreet found had been grown by the Menominee in those ancient beds. One of the methods she is testing is also based on the archaeological evidence at that site, which suggests that the Menominee may have used biochar—the solids left over from burning something organic—to fertilize the fields.

Elder hopes that some day the tribe will be able to grow enough to become self-reliant. Across from her office, the College of Menominee Nation’s Community Technology Center has fields and a greenhouse where Jeremy Wescott, a nutrition and outreach coordinator, and Violet Bia, greenhouse manager, experiment and teach gardening as a way to address food scarcity on tribal lands.

Pre-colonization, the Menominee lived across central Wisconsin, all along Lake Winnebago, up the entire Door Peninsula, and farther north along Green Bay until the Upper Peninsula. So when the Menominee were forced off that land and confined to their current territory, a lot of agricultural land was lost. While some families continued to grow their own food, some of that knowledge was lost over the decades.

“They lost their access to the land, therefore they didn’t have access to their gardens,” Elder said. “At the same time, the Menominee people were put on the reservation and the government then at that time said they’re going to take care of the Indians. They had subsidized the whole shift in their lifestyle. It was changed. And so as that next generation came, if you don’t teach that next generation, that’s going to be lost.”

Fresh produce is difficult to find and expensive, which was why the college started teaching community members gardening and started a farmers market where community members could sell any excess produce. In the greenhouse, researchers are testing if they can get a pinecone to sprout, determining which herbs can keep over the winter, and storing a coop for Henny Penny, a speckled hen. Peppers and chilis hang from the ceiling to dry. While the pandemic put a lot of workshops on hold, it also underscored how easily food systems can be disrupted and reinforced the importance of self-reliance.

Into the Woods

In his book, “Good Seeds; A Menominee Indian Food Memoir,” Thomas Pecore Weso described a food culture centered on what his grandparents grew in their garden, including flint corn and squash, as well as what could be gathered, fished, or hunted in the forest. As a result, he developed an intimate knowledge of his environment and the seasons.

For example, Weso’s strength was as a hunter. One staple of his diet was partridge—which doesn’t migrate, making them available year-round—and he noticed that the timing of when he caught the bird affected its taste.

“In the spring when busy giving birth and raising families, they eat a high-protein diet of insects. Later, in the summer, they eat fruits, seeds, and nuts,” he wrote. “In the late autumn and winter, they eat sweet berries off the staghorn sumac and other berries. Their meat in the late summer is sweet because of their diet of blackberries and cranberries. The winter meat naturally has less fat and tastes tangier.”

The same can be said for plants gathered from foraging. Weso’s book includes a recipe for fried dandelion greens that are picked as young shoots and for dandelion wine that uses the yellow fuzz from the bloomed flowers.

As Wisconsin moves into winter, Terry looks forward to hunting season—not as a hunter, but as a butcher. Like Alegria, she looks forward to ramps and maple syrup season in the spring. Foraging is also about knowing when to pick something and when to leave it alone so it can continue to propagate.

“In order to be able to really appreciate the flavors and the plants for what they provide for us, you have to recognize the seasonality,” Terry said. “It’s spending the time with somebody, it’s the conversations that you have during those moments, and then it’s being able to have that mindfulness of your space and what the earth is providing for you.”

Terry pointed out that food is never just about food.

“Everybody has to eat,” she said. “And so how we choose to do that and how we choose to nourish ourselves and not just consume is huge. Especially when you connect it to culture and tradition and mindfulness and intention.”

By maintaining her connection with Ho-Chunk cuisine, Terry reinforces her connection with her family, her ancestors, her environment, and her culture. She is working so she and other Indigenous peoples can share and revitalize those connections for the next generation.

“These meals that we share, even interacting with the plants or the animals is honoring our culture and tradition and bringing us back to a space where our ancestors knew how important it was for us to have this information,” Terry said. “Every time I go out and pick milkweed, I remember my great-grandma and these picnics we had and her talking in Ho-Chunk with me and thinking how I can provide that for the next generation.”

Politics

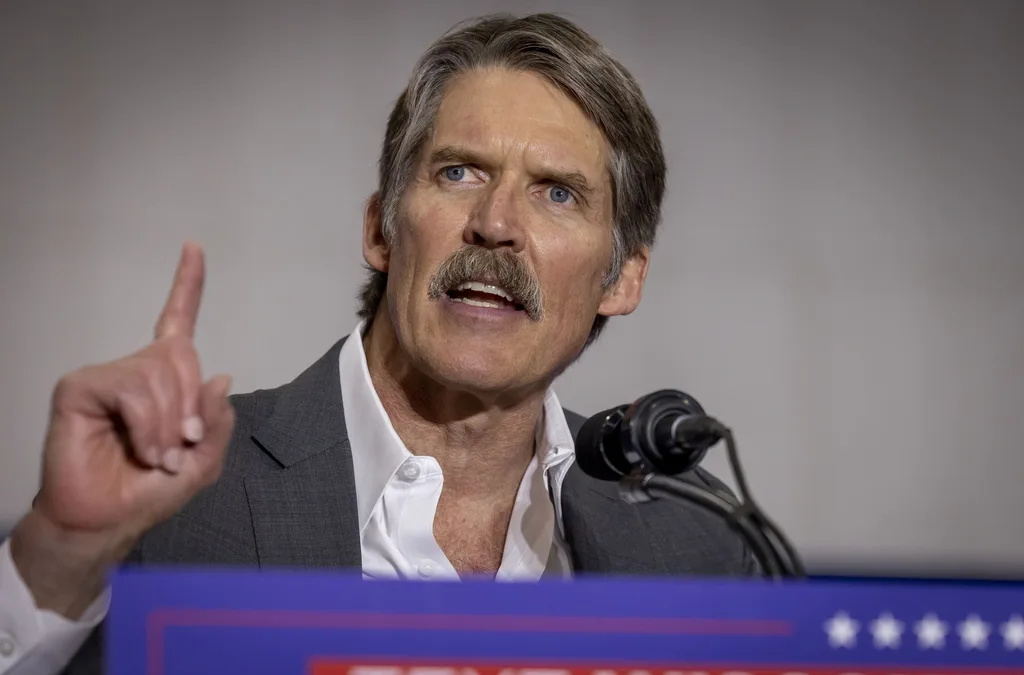

Eric Hovde’s company exposed workers to dangerous chemicals, OSHA reports say

A Madison-based real estate company run by Wisconsin US Senate candidate Eric Hovde settled with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration...

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...