#image_title

#image_title

As Labor Day 2021 rolls around, Wisconsin workers face their greatest opportunity for wage growth and unionization in years.

When Phil Swanhorst started working as an Eau Claire municipal bus driver in 2001, his health insurance and retirement were entirely paid for by the city; he had other fringe benefits, such as an allowance for work clothing; and he had a competitive wage.

Then in 2011, Wisconsin’s Republican leadership passed Act 10, former Gov. Scott Walker’s legislation to restrict public union’s bargaining power. By the time Swanhorst retired in 2017, he had to pay 50% of his retirement, 18% of his health insurance and his wages “weren’t even keeping up with inflation for the last five years of my employment.”

“In 15 years time, my take-home pay from when I started to when I ended stayed about the same,” Swanhorst said. “And that’s what happened to a lot of public sector workers.”

Swanhort’s plight is all too familiar to other Wisconsin workers, who have watched their benefits erode and wages stagnate. The trend worsened in the past decade, but it has been an issue for nearly 50 years. But as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the pendulum is swinging back the opposite direction as workers find themselves with more leverage than ever amid a labor shortage and the beginning of a resurgence of union power.

UW-Madison’s Center on Wisconsin Strategy (COWS) released its annual State of Working Wisconsin last week. It showed union membership nationwide has been declining since it peaked in 1964. At that time, 1 in 3 Wisconsinites belonged to a union but by 1996, it was 1 in 5 Wisconsinites.

Wisconsin still had a higher rate of unionization than the rest of the country until 2012, after Act 10 was enacted. Today, just 1 in 10 Wisconsinites belong to a union.

Swanhorst, who is now president of the Greater West-Central Area Labor Council, said that almost a decade later, the general public is starting to realize Act 10 had an impact on all workers, not just public employees whose wages and benefits were immediately reduced.

“It did not happen overnight; it wasn’t intended to happen overnight,” Swanhorst said. “It’s worked exactly as they intended. It’s taken years to accomplish and people have just forgot about it until now.”

But after decades of declining membership, organized labor is having a moment.

In November, 2020, workers at the Milwaukee Art Museum voted to join the International Brotherhood of Machinists and Aerospace Workers District 10, which also represents the museum’s security guards. A few weeks later, Wonderstate Coffee employees joined the International Brotherhood of Teamsters Local 334, saying they hoped to use their bargaining power to bring their wages up to $15 an hour.

Milwaukee janitors under a new union contract are now earning $15 an hour, Colectivo Coffee’s 300 baristas, bakers and other staff voted last month to join the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, and the owners of Bounce Milwaukee announced its workers would be able to seek a labor contract through the Milwaukee Area Service & Hospitality Workers Organization (MASH).

Swanhorst said union support has ebbed and flowed over time, but the combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and the pro-labor stance of the Biden administration has ushered in new interest in organized labor.

RELATED: New Union Contract for Milwaukee Janitors Could Be a Model for the State’s Whole Service Industry

“I’ve seen [Biden] utter the word ‘union’ more times in his first eight months in office than I’ve heard a president utter in the last eight years out of Washington,” Swanhorst said. “At least the general public is aware unions have got to be a part of our society. They’re what created the middle class, and we need to keep them there to maintain our middle class.”

Collective bargaining isn’t only about wages. Peter Rickman, president of MASH said that during his involvement with the Milwaukee janitor’s contract, he heard about how cleaners were instructed to use different chemicals to clean during the pandemic, but were not taught how to do so safely. Their positions were also downsized as many professionals worked from home, but when those workers returned to the office, the number of cleaners wasn’t brought back up to pre-pandemic levels.

“Frontline workers, janitors, are some of the most disregarded and left-behind workers in society,” Rickman said. “We’re able to, through their union, assert things that had literally nothing to do with the economics and everything to do with what their working lives were like. And frankly about protecting others besides themselves too.”

Pam Fendt, president of the Milwaukee Area Labor Council, said the pandemic made many frontline workers question whether their jobs were worth the risk.

“Most workers didn’t plan on facing the possibility of a deadly situation every time they went to work,” Fendt said. “Certainly, every time a police officer leaves the house to go to work, they might think that, but I don’t think that the average teacher or grocery store clerk would think that. I think that it caused a situation where people said, ‘Is this worth it?’”

That’s one reason why Rickman said MASH in particular is focusing on the food and beverage industry, cleaning services, and security for opportunities to organize. Many of those positions are subcontracted, but Rickman said that if you get the head of the company or building that is doing the subcontracting to the table, they could set standards for those subcontractors.

“[MASH] is focused on going up the chain of capital and saying to the real bosses here, ‘You need to be at the table, but you need to agree that no matter who’s doing this subcontracted work, they’re going to be living-wage union jobs,’” Rickman said. “I’m pretty excited, honestly, because it implies a different way of organizing, that’s not rooted in going banana stand by banana stand.”

Fendt said they’re also looking at industries that haven’t been organized before.

“Now is not the time just to rest in our status quo. I think we need to be out there pushing the boundaries a little bit and really seeing what sectors are receptive to organizing drives,” Fendt said. “Drugstore workers haven’t traditionally been organized. Does that mean it can never be? Maybe we’ve written off sectors or we tend to look to expand only in sectors that already have a base. Look a little wider at different sectors of the economy to see what might be a good organizing target.”

Rickman said it’s going to take more than public and political opinion to create real change. US labor laws were passed in the 1930s, which Rickman pointed out is closer to Civil War than 2021. Those laws need to be updated to reflect the reality of work in the 21st century, he said.

“In the capitalism of the 21st century, the rules of the game, the system has been rigged against working class people,” Rickman said. “We need to un-f**k the system. We need to balance the power between the boss class and the working class by putting workers at the table with a real voice.”

House Democrats passed the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act in March, which would provide protections for workers trying to organize.Union leaders said such a provision would begin to level the playing field between workers and employers. But the bill has stalled in the Senate due to the lack of Republican support.

Politics

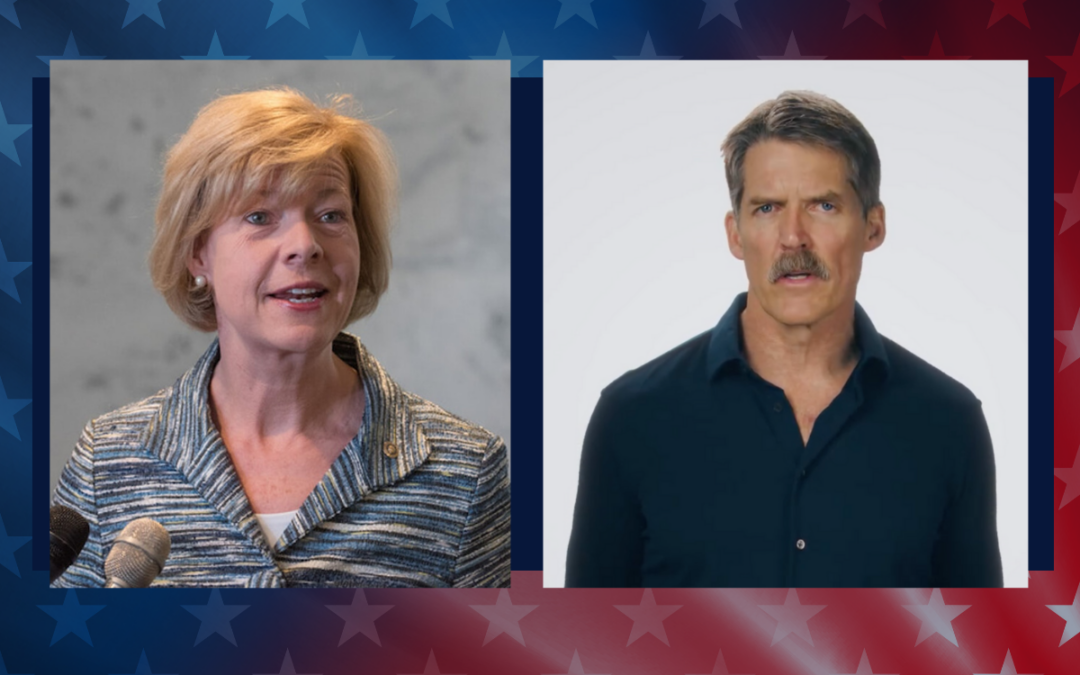

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Who Is Tammy Baldwin?

Getting to know the contenders for this November’s US Senate election. [Editor’s Note: Part of a series that profiles the candidates and issues in...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...