#image_title

#image_title

Citizen lobbyists seek solutions on a variety of crises

Advocating for clean water used to be simpler. Everyone supports clean water.

But to lobby for certain actions to clean up water in Wisconsin now requires specificity: Are you talking about water contaminated by industries that used “forever chemicals,” water tainted by farm operations, water running through old lead pipes, well water spoiled by old septic systems overdue for replacement, or water shortages caused by high capacity wells used in growing industrial size crops?

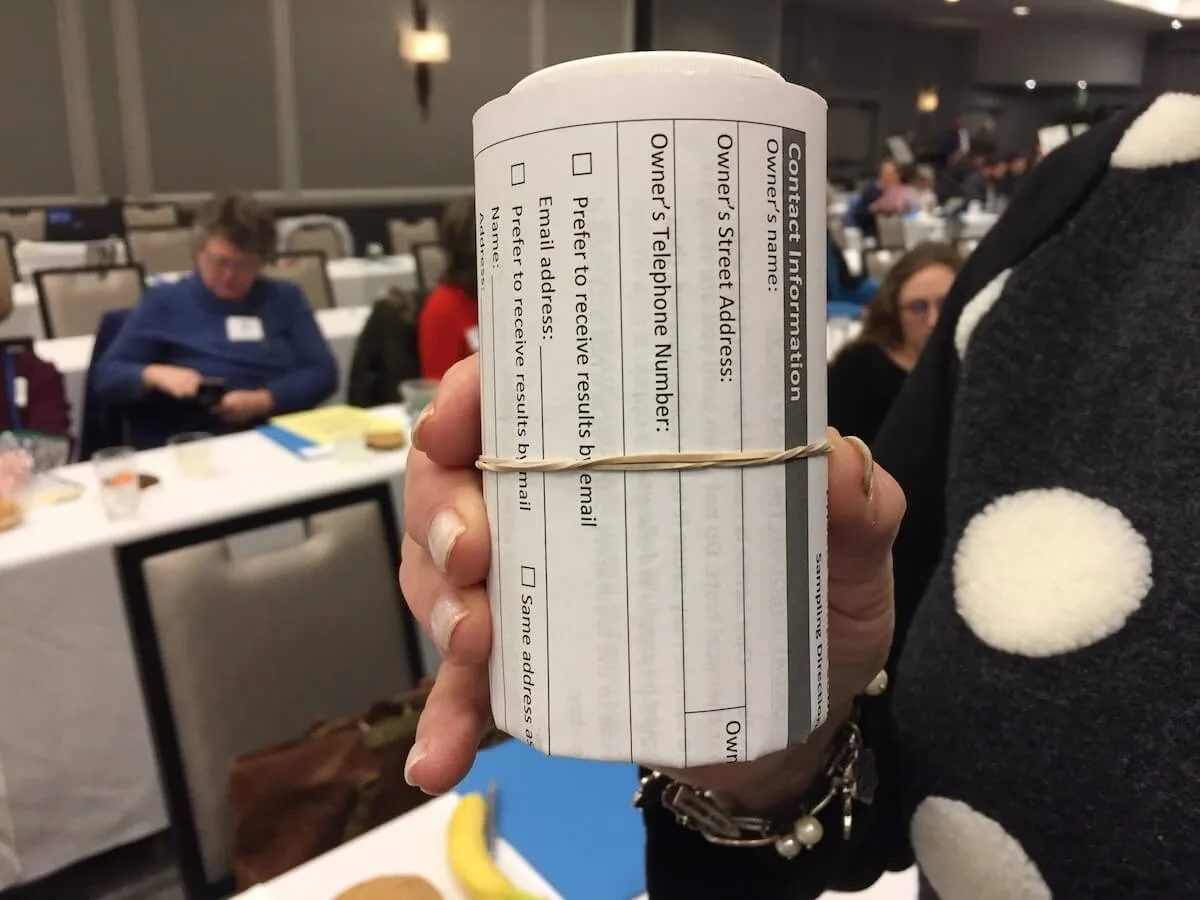

Those problems and more were tackled by more than 250 attendees of Thursday’s Clean Water Lobby Day in Madison hosted by Wisconsin Conservation Voters.

Reports of groundwater contamination are becoming more commonplace in western Wisconsin, said Charlene Warner, who lives south of Eau Claire in the town of Brunswick. Cities treat water, she said, but many rural residents don’t realize they need to test their wells to ensure their water is safe to drink.

“We have a smug attitude that out water in this part of the state is so clean,” she said. “But that isn’t always the case.”

When Bruce Neeb moved into his home in the town of Wheaton in Chippewa County 23 years ago, he quickly learned the water there was anything but pure.

The water in Neeb’s home had high nitrate levels. He had to check the water frequently, then pay for a process to lower the level of nitrates, a substance known to cause birth defects and cancers.

Neeb, a retired grants and loans administrator with the state Department of Natural Resources, eventually moved from that home. He no longer deals with high nitrate levels in his water.

“People typically don’t think about clean water being an issue in our part of the state,” Neeb said in reference to northwest Wisconsin. “But in some cases, it is becoming a real problem.”

After a lobbying session at Madison’s Concourse Hotel to discuss state water concerns, the group headed to the Capitol to talk with lawmakers about pending water-related legislation.

From drinking water problems in Marinette County, to issues with lead leaching into water in Milwaukee and other cities, to concerns about manure contaminating drinking water in rural regions, polluted drinking water is prompting headlines across the state, said Kerry Schumann, executive director of Wisconsin Conservation Voters.

Water pollution poses a variety of health concerns for state residents, she said, along with rising health care and emotional costs.

“There are so many people in this state who can’t turn on their tap and drink their water,” Schumann said. “That’s just not right.”

Drinking water has garnered increased attention since Gov. Tony Evers declared last year the “year of clean drinking water” during his inaugural State of the State address.

Earlier this month, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos’ Water Quality Task Force released a list of proposed bills intended to address water quality issues in the state. The roughly $10 million investment in water quality improvements included such measures as creating an Office of Water Policy and changing the well compensation grant program.

Critics, including Jennifer Giegerick, WCV’s government affairs director said those proposals don’t go far enough. She said those recommendations “are insufficient to address the major water problems in our state.”

Katie Doss of Milwaukee agrees. Her 4-year-old granddaughter has significant health problems that doctors attribute to her exposure to lead via paint and water, Doss said. High lead levels can cause anemia, weakness and kidney and brain damage, among other health concerns.

“I’ve known a lot of people in my city who are suffering from lead poisoning,” she said. “Now it has hit my family.”

Unsafe lead levels continue as an issue of concern in Milwaukee, where much of the city’s utilities system is composed of lead pipes and peeling lead paint is prevalent in many homes in older, poor areas. In 2016, more than 1 of every 10 children tested had blood lead levels higher than what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers safe.

Replacing city utilities will be a costly venture, Doss said, and isn’t likely to happen soon. She said state legislators should crack down on landlords to ensure they paint over lead paint and install filters on faucets to screen out lead.

“There are things we could do. We’re just not doing them,” said Doss, who works to educate inner city residents about how to prevent the ingestion of lead.

Madison resident Susan Kennedy is concerned about the state’s drinking water too. She said she drinks clean water in her home, “but I know a lot of people who can’t.”

Eleanor Wolf said large-scale farms and the prevalence of high-capacity wells pose growing threats to safe drinking water in Wisconsin.

“We need to look at water as a really valuable resource. We have to protect it. If we don’t have clean water, we don’t have much,” said Wolf, a resident of Eau Claire, a place where clear water is literally in the name.

Politics

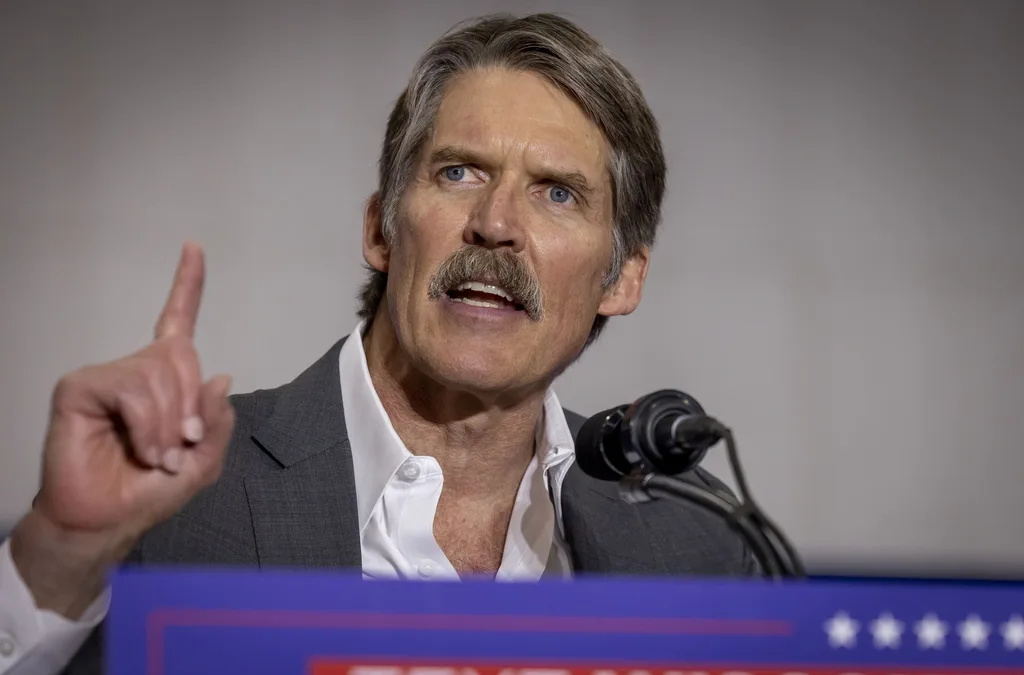

Eric Hovde’s company exposed workers to dangerous chemicals, OSHA reports say

A Madison-based real estate company run by Wisconsin US Senate candidate Eric Hovde settled with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration...

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...