#image_title

#image_title

Black Milwaukeeans struggle with ‘essential’ status, lack of health care, and community divestment as COVID-19 rips through the city.

Coronavirus has no motive. It does not target any race or gender or city. It does not care whether it infects a well-to-do businessman or a struggling dairy farmer.

But a virus does recognize disparities. And then it exploits them.

That’s exactly what it has done in Milwaukee, where 944 of the city’s roughly 1,750 coronavirus patients are black, a number greatly disproportionate to African Americans’ 38 percent share of the city’s population. Seventy-four of the 134 deaths in Milwaukee County have been black residents, even though they only make up 27 percent of the county’s population. The picture is similar in metropolitan areas across the country.

Centuries of racial inequality have set up a perfect storm for black Americans with a lack of reliable, close health care and a predisposition to conditions that exacerbate COVID-19. Mismanagement by the federal government all the way up to President Donald Trump has let the virus take hold in every state, leaving virtually every citizen touched by the crisis.

And so coronavirus continues to ravage Milwaukee’s black community, even as right-wing protesters take to the streets around the country to demand an end to stay-at-home orders.

“We don’t have some of the same resources as other areas getting hit by this,” said Eddie Roberson, a 50-year-old African American truck driver from Milwaukee.

On the city’s predominantly black north side, the community has struggled to recover after deindustrialization sucked an unprecedented amount of jobs out of the city in the 1960s and 1970s.

A.O. Smith, which once employed 10,000 and served as a ticket to the middle class, is just one of numerous factories that are gone. The collapse of the industrial core caused trauma that still echoes to this day.

“As you continue to really break it down just to understand how deep this goes, you can definitely see the effects,” said Rep. David Bowen, a Democratic state legislator representing Milwaukee’s north side. “The folks in my community were told to work those manufacturing jobs, and those jobs just disappeared.”

Today, Milwaukee’s metropolitan area is among the most inequitable for African Americans as poverty and unemployment have skyrocketed and wages have fallen. It is one of the most segregated cities in America. Last year, County Executive Chris Abele declared racism a public health crisis.

Since 2006, the only major north-side health care provider has been St. Joseph Hospital. As the area surrounding it has become poorer and more minority-majority, the hospital has cut services and about two-thirds of the facility is vacant.

“St. Joseph’s is a shell of itself,” Roberson said. “You can go there for medical treatment, but I wouldn’t advise you to.”

Ascension Wisconsin, which planned further cuts to St. Joseph in 2018, backed off after sharp rebukes from local leaders. The community remains skeptical.

“A lot of people don’t even feel comfortable going to it,” said Angela Lang, executive director of Black Leaders Organizing for Communities, a voter-mobilization group on the north side.

The north-side health care desert also means that likely coronavirus patients have further reduced access to much-needed tests. Bowen had COVID-19 but recovered.

He believes he transmitted the virus to three of his friends before he was diagnosed, but only one was able to get a test, which came back positive.

“What we know is that this virus finds your largest inequities and it shows itself in those places the most,” said state Sen. Lena Taylor, a Democrat representing the north side.

Asthma, hypertension, heart disease, and obesity — all conditions that increase the risk of severe coronavirus complications — are disproportionately present in African Americans compared with the rest of the population. Food deserts, health care deserts, poverty, and a lack of insurance coverage compound these risks.

“It’s really important that people realize that those disparities get lessened when folks have access to preventive care on a regular basis,” Bowen said. “There are a lot of people in our community that are avoiding having to deal with those costs, because we don’t have universal health care. I think it’s time we have a real serious conversation that every man, woman, and child needs health care at the end of the day.”

Taylor does not need to stop to think for even a second about the virus’ impact on the black community. She is able to list numerous examples of black Milwaukeeans suffering from the virus, spanning family, friends, and community leaders.

She said the state’s coronavirus relief package does not do enough to help the black community. Other Democrats have already called for additional relief.

“Where are we putting action in to address the inequities we already know exist in our state?” Taylor said. “And I know that we know, because I’ve stood on the floor and talked about them — a lot.”

‘A crisis within a crisis’

Thirteen percent of black Wisconsinites are uninsured compared to 6 percent of all residents, according to the state Department of Health Services. State Republicans rejected Medicaid expansion last year despite overwhelming public support. Medicaid expansion helps greatly reduce the number of uninsured residents in a state.

Even though millions of people are working from home during the pandemic, less than a fifth of black Americans are able to do so, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Almost 40 percent of black workers are deemed “essential,” according to analysis by The Guardian.

“Someone said before, ‘We only use the word “essential” because “sacrificial” is too real,’” Lang said. “I think that’s true. The people on the frontlines … a lot of them tend to be low-wage workers, and they tend to be black and brown. They are the ones constantly putting themselves at risk in order to make sure that we’re getting what we need.”

Gov. Tony Evers has called the disproportionate amount of black Milwaukeeans infected with coronavirus “a crisis within a crisis.” On Monday, Milwaukee Alderwoman Chantia Lewis, who represents the far northwest side, pleaded for help from the state.

“Those living in communities with glaring health disparities are in grave danger,” Lewis said in a statement. “I pray that working with State and City partners we can stop the spread quickly and (hopefully) save as many lives as possible.”

State Republicans have so far been unwilling to help out Milwaukee’s minority communities, even going so far as to force in-person voting for the April 7 election, even though Milwaukee only had enough poll workers to staff five out of 182 polling places. Many called it voter suppression, forcing people to choose between their health and right to vote.

The result was about 20,000 city residents waiting in line for up to three hours at five different high schools around the city. So far 19 COVID-19 cases have been traced back to the election, and more are likely on the way as contact tracers investigate new cases.

“I don’t think anyone’s really surprised by it,” Lang said. “I think we all knew it was coming, and I think a lot of us anticipate those numbers increasing in the next couple days and in the next couple weeks. But it doesn’t make it any less heartbreaking.”

In order for the African American community to not end up disproportionately affected in the event of another pandemic, Lang said elected officials need to make policies that further protect low-income individuals.

Those include providing personal protective equipment to all essential workers, ensuring paid sick days, expanding testing, providing universal basic income during the health crisis, and suspending evictions and rent payments for unemployed workers.

Roberson would like to see more investment in health care in predominantly black areas.

“Hospitals are disappearing from our community,” he said.

During a virtual state Senate session this month, Taylor and fellow Milwaukee Democrat Tim Carpenter, who represents the heavily Latino south side, were muted by Republican Senate President Roger Roth and not allowed to speak.

Taylor said if she had been able to speak, she would have told stories of real people suffering during the pandemic and advocated for more aid to go their way.

The often-fiery Taylor said Roth’s casual disregard for her community “caused me to be speechless, which is not me.”

“I just don’t understand the humanity a person has who refuses the voice of those people, and refuses to act on behalf of our people,” Taylor said.

Politics

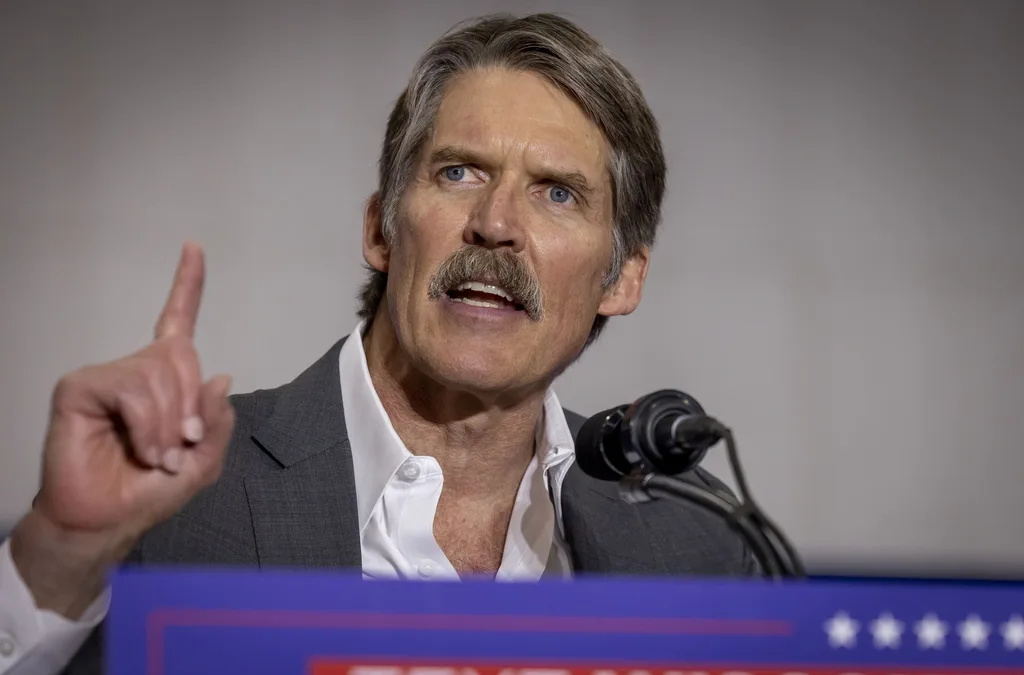

Eric Hovde’s company exposed workers to dangerous chemicals, OSHA reports say

A Madison-based real estate company run by Wisconsin US Senate candidate Eric Hovde settled with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration...

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...