#image_title

#image_title

A corporation impedes progress on tracing and fixing PFAS contamination in the local water supply—pollution that it caused.

Editor’s Note: This article was published in collaboration with The Wisconsin Idea, a project of In These Times magazine.

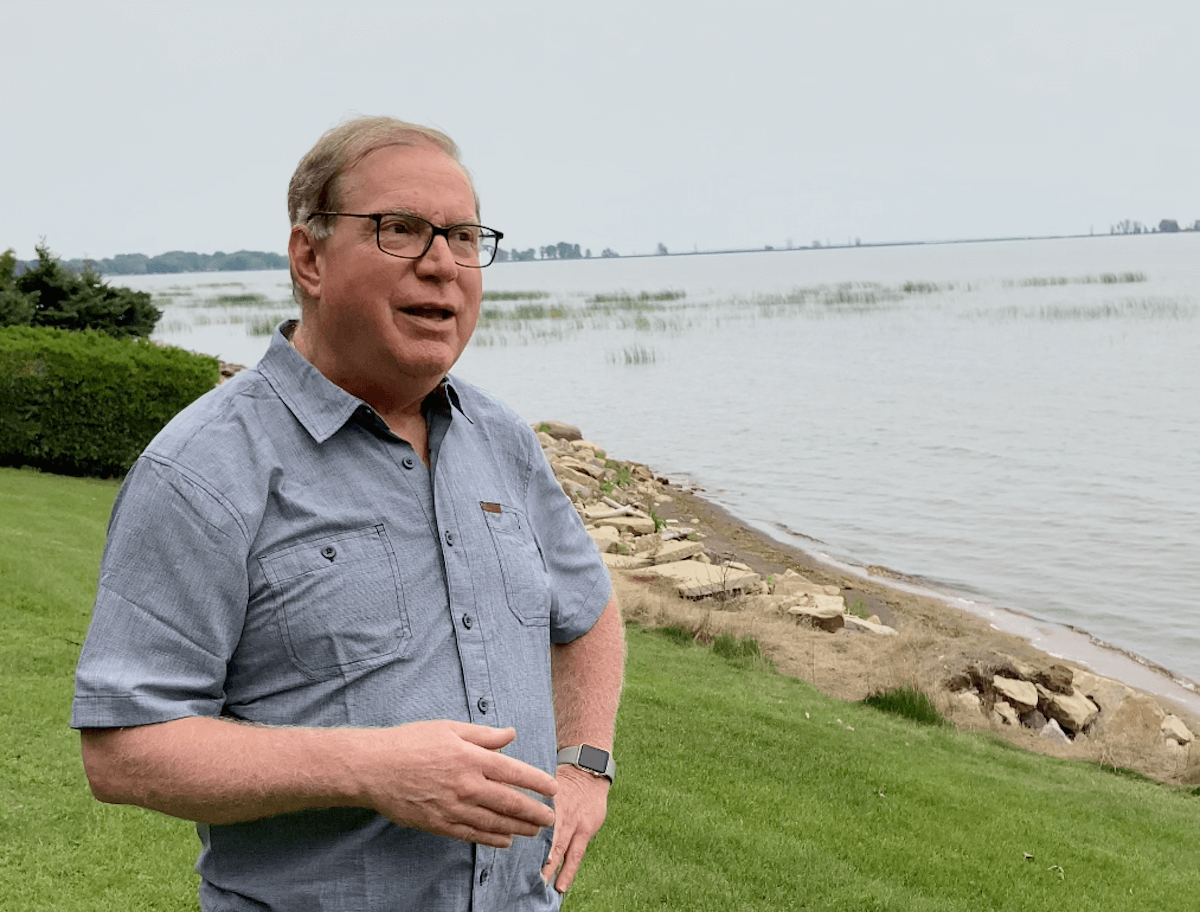

Chuck Boyle drives around Marinette and the Town of Peshtigo, regularly pulling over at places where creeks and drainage ditches intersect with the road. Born and raised in Peshtigo, an unincorporated township along Green Bay, Boyle has mapped these waterways out in his head, knowing where the water comes from and where it flows.

More often than not, Boyle sees the telltale bright white, almost luminescent foam building up in the creeks’ nooks and crannies: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, more commonly known as PFAS.

PFAS, man-made chemicals shown to have adverse health impacts, have spread through the area’s waterways, wastewater system, agricultural land and residents’ wells. But years after the contamination was disclosed, its extent and its impact on the community has still not been fully assessed. Instead of proactively addressing the issue, residents, local politicians and state regulation agencies have had to push the responsible company to fully reconcile the damage done.

PFAS contaminants are commonly found in products like firefighting foam and stain-resistant sprays. Nicknamed “forever chemicals,” they do not break down naturally and have been linked to medical conditions such as low birth weights, cancer, and thyroid hormone disruption, and they can suppress antibody production, limiting the immune system’s ability to fight infection and reducing the effectiveness of vaccination.

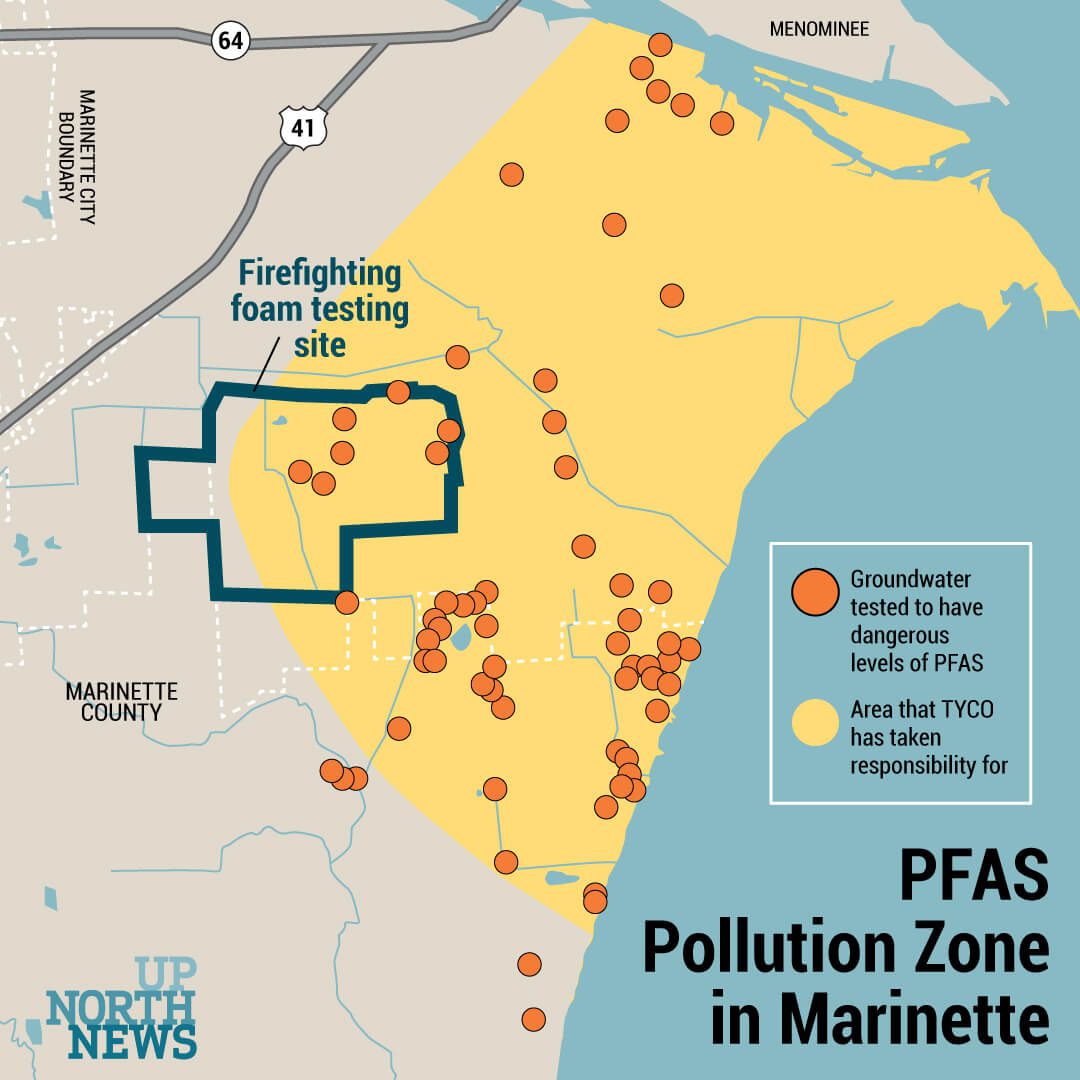

In 2013 Tyco Fire Products, a firefighting foam manufacturer, discovered that its foam testing facility had been releasing the toxic contaminants into area groundwater. It’s unknown for exactly how long the foam has been leaking into the groundwater, but it could be decades; Tyco had tested foam at that site since 1962. The company, however, only briefly mentioned the contamination in a 2,300-page report to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) in 2016 and did not alert the public until late 2017.

The Environmental Protection Agency designated PFAS levels above 70 parts per trillion (ppt) as potentially hazardous to human health. The DNR’s groundwater testing in Marinette has found one PFAS compound, Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), at levels as high as 254,000 ppt, and another compound, Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) at levels as high as 64,000 ppt.

When the contamination was first made public, Boyle started organizing what would become Save Our H2O, a group of area residents that monitors PFAS contamination and urges Wisconsin’s Department of Health Services (DHS), the DNR, and Tyco (which merged with Johnson Controls International in 2017) for more testing and filtration.

RELATED: Marinette is Letting PFAS Polluters Off the Hook, Alderman Says

While that pressure has led to some action–growing awareness of PFAS, a bill in the statehouse limiting the use of PFAS-laden firefighting foam, warning signs along contaminated waterways and expanded testing–much remains undone.

In 2020 the DNR proposed setting a PFAS groundwater standard of 20 ppt, but industry lobbyists thwarted that regulation. At the behest of Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce, the state’s largest business lobby, the proposed rule was tabled by the DNR Board, and the agency is unable to enforce PFAS contamination regulations. Meanwhile, more of these contaminants are being detected across the state. In July of this year, the city of Eau Claire discovered unsafe PFAS levels in one quarter of its municipal wells.

As a temporary (and ongoing) solution in Peshtigo and Marinette, in 2017 the DNR ordered JCI/Tyco to install filtration systems and provide bottled water to the over 140 residents with wells known to be contaminated. This August, Tyco broke ground on a system that will extract and filter groundwater, reducing PFAS to a level yet to be set by the DNR before dumping the water into a ditch that runs into Green Bay.

The system will not remove all of the area’s PFAS contamination, nor will it address the contaminants in residents’ wells.

Residents who have been watching this issue closely are concerned that there still hasn’t been a full account of the extent of the contamination and its impact on the community. Many also suspect that this latest effort to clean the groundwater is the company’s way to wash its hands and walk away from the damage it’s done.

How Far Has it Spread?

One of Boyle’s first recruits to help monitor PFAS contamination was Jeff Lamont, another longtime Peshtigo resident and recently retired hydrogeologist. Lamont has cleaned up contamination sites across the country, including a project to remediate the Menominee River, which Tyco contaminated with arsenic.

According to Lamont, because PFAS don’t break down as they move through water systems—such as rainwater to groundwater, streams, and lakes—they can spread much further than organic chemicals.

“These compounds just zoom right through an aquifer unretarded,” Lamont said. “They last forever. The half-lives of some of these compounds are in the decades.”

The creeks that Boyle regularly inspects are miles away from the designated contamination zone, which is centered on the firefighting foam testing site and contains waterways downstream. Tyco claims it is not responsible for PFAS found outside the contamination zone, and has pushed the DNR to identify other sources.

“[Tyco] just says it’s not theirs,” Lamont said. “Well, it’s in close proximity to theirs and we know [of] no other sources.”

Then there’s the foam floating on the surface of ditches, streams and along the coast of Green Bay. In 2019 Tyco installed booms to collect and dispose of the foam along several creeks, but stated that the foam was formed naturally, by the turbulence of wind and water. The DNR tested this foam in June, however, and found PFOA levels of 23,000 ppt and PFOS levels of 63,000 ppt of PFOA—far above the DNR’s recommended safe limit of 20 ppt. The surface water also tested for high concentrations of PFAS, with 130 ppt of PFOA and 2,000 ppt of PFOS.

While Tyco has since acknowledged PFAS levels in the foam, it stands by its earlier statement that the foam was naturally occurring and not a PFAS source. In an August email, a Tyco spokesperson told UpNorthNews, “because there is PFAS in the surface water and PFAS aggregates in foam, we expected there was PFAS in the foam, which is why we have always sent the collected foam for disposal at a licensed facility out of state.”

When asked about the company’s previous assertion that the foam is occurring naturally, the spokesperson then quoted a June DNR letter to the public regarding foam testing, which stated “foam frequently collects on the surfaces of water bodies where wind and wave action pushes it to the shore…[sic] Natural foams develop when plants or other naturally occurring materials break down and water becomes enriched with nutrients.”

But the DNR quote is incomplete. The ellipses from Tyco’s email left out a key sentence in the DNR’s letter, which says that “both natural processes and pollution contribute to the formation of surface water foam.” The last sentence in that same paragraph reads, “spills, discharges or runoff contaminated with cleaning agents, PFAS-containing firefighting foam, or other chemical contaminants can contribute to foam formation events that are non-natural in origin.”

In late July, Lamont and Boyle met in Boyle’s backyard along Green Bay. As they talked, Boyle’s little dog splashed around the water’s edge. Boyle commented he’d need to give the dog a bath—the foam was gathering on the shore where his dog played.

Lamont worries they still don’t know the full extent of the contamination.

When residents outside of the contamination zone tested their water–on their own dime–and found PFAS, the DNR ordered Tyco to expand its investigation zone. In late 2020, the DNR formed a new team to investigate the extent of the contamination and collaborated with Wood Environment & Infrastructure Solutions to test over 500 wells that Tyco refused to test.

In a July public hearing, the DNR announced the results of that testing: Of the 415 that agreed to testing, 85 had no PFAS detected; 298 had some, but less than the recommended environmental standard of 20 ppt; and 32 had levels above the standard, ranging from 21.9 to 273 ppt.

Public Awareness

When PFAS contamination was first announced, Doug Oitzinger did not want to get involved. After working for Fincantieri Marinette Marine for 22 years, he had gone into partial retirement, served as mayor of Marinette for five years and opened up a coffee shop. By the time PFAS had come to light, Oitzinger had left office, sold the coffee shop and fully retired.

Oitzinger’s understanding was that Marinette’s water supply was safe and Tyco was meeting with the people in the Town of Peshtigo whose well water had been contaminated. He thought the situation was being handled and he didn’t need to be concerned.

That changed in the spring of 2018, when he noticed that his church’s community garden had a well in the contamination zone, which, luckily, wasn’t being used. The church and nearby residents, Oitzinger learned, did not know about PFAS pollution in Peshtigo, nor that they were located in the contamination zone. “It was at that moment I knew my city does not know what’s going on,” Oitzinger recalled.

Later that year, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services issued a memo to residents of Marinette and Peshtigo warning gardeners against using water contaminated with PFAS above 70 ppt, a recommendation in line with the US Environmental Protection Agency.

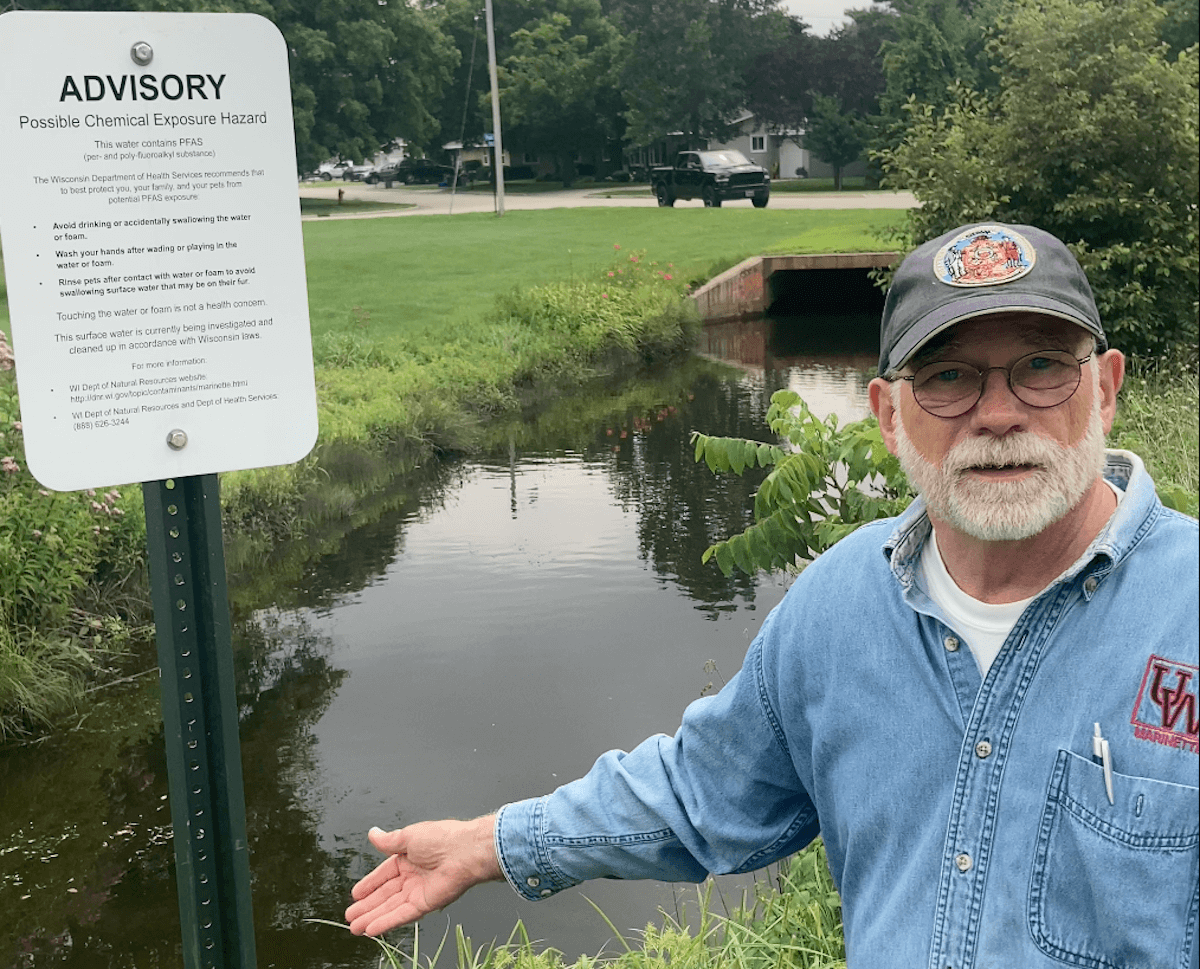

At the corner of the church lot is an open drainage ditch surrounded by plants and marked with a white 18×12 inch sign. From a distance the only word that can be read is “ADVISORY.” Moving in closer, the words just below become legible: “Possible Chemical Exposure Hazard.”

A representative from Tyco told the DNR and DHS that, “due to public comments and requests for information,” the company decided to put up signs along open-air drainage ditches that contain PFAS. But residents, Oitzinger said, had hoped it would have a graphic that children could understand.

“Human beings, especially children, are drawn toward water. They like to play in it,” Oitzinger said. “A child’s not going to read ‘Advisory.’”

In smaller print, the sign warns not to ingest the water or foam and to wash hands and pets after wading in the water. But right under that in larger print, it says, “Touching the water or foam is not a health concern.” Oitzinger and other residents are asking to have the signs changed.

“It’s better than nothing, but man, we could do a lot better,” Oitzinger said. “And that’s almost always what my response will be if you start asking me about Tyco. ‘Well, what they’re doing is better than nothing, but they could do a lot better.’”

Tyco said it is working with the DNR to create and install new signs, as well as increase the number along ditches, but it’s unknown how long this will take.

Down This Road Before

Before Tyco got approval for its Groundwater Extraction System (GETS), Oitzinger was unhappy with what he said was inadequate communication about the project to residents.

GETS requires nine extraction wells to be installed throughout the contamination zone. Before Marinette City Council voted to approve the plan, Oitzinger, who re-entered politics and is now a Marinette alderman, talked to residents in his district whose yards will house the electronic panels controlling the wells. Although Tyco said the company “has been exhaustive in our efforts to communicate with the community about the [water filtration system],” such as through media interviews and distributing fact sheets, Oitzinger said his residents didn’t know anything about it.

This isn’t the first filtration system Tyco has installed. Tucked away in the far corner of a retirement community sits a shed about two-stories tall, filtering water from a nearby creek before it flows out to Green Bay. In August 2020, PFAS levels 10 feet downstream of a treatment system were 50 times higher than the recommended levels, even after being treated. Tyco blamed high water levels and a rainier-than-usual summer for the excess contamination, stating that “the current situation at Ditch B is not up to our standards as an environmental leader and we will do everything we can to resolve it quickly.”

Unanswered Questions

Four years after the contamination was disclosed, questions linger about the extent of the pollution beyond the area’s waterways.

Up until March 2018, Tyco also dumped PFAS-contaminated firefighting foam into Marinette’s wastewater treatment system. Wastewater districts across the country use biosolids, a byproduct of wastewater treatment, as fertilizer to be spread across surrounding agricultural land. PFAS is not adequately filtered out by current wastewater treatment systems, contaminating these biosolids.

Now the city has to ship its biosolids to a special facility in Oregon. Oitzinger hoped the new GETS system, which will be built partially in the city’s right-of-way, would be an opportunity to recoup the additional costs of disposing of its biosolids, but city officials opted not to charge Tyco for its use of the city right-of-way.

Beyond the cost of shipping biosolids, Oitzinger worries about the decades of dumping PFAS-contaminated biosolids on agricultural fields. Despite these concerns, requests for an investigation into whether PFAS have entered the food system, through the crops grown on that land or the animals that grazed on those crops, have been rebuffed by the DNR, DHS and Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection.

“Taking a milk sample and analyzing milk for PFAS is no different than taking water from a well and analyzing it,” Lamont said. “I’m afraid that they’re concerned about the negativity about it. If we know it’s in the food supply—the sweet corn we’re eating, the cattle we’re eating, the milk we’re drinking—it’s not gonna look pretty in the dairies.”

Driving around Marinette and the Town of Peshtigo, both Oitzinger and Boyle point out house after house, giving an oral epidemiology report: cancers, thyroids removed, pets that died painful deaths. While there has not yet been an epidemiological study conducted in Marinette or Peshtigo measuring the full extent of the health impacts, many have stepped forward to share their stories, including at a public hearing with State Attorney General Josh Kaul.

“Anecdotally, we have a lot of cancer in this community,” Oitzinger said. “Anecdotally, we have a lot of thyroid problems in this community. Anecdotally, testicular cancer was off the charts.”

Residents also look to epidemiological studies conducted in towns with similar PFAS contamination across the country.

As part of a settlement with DuPont, epidemiologists studied the health impacts of PFOA, also known as C8, in the Mid-Ohio Valley. The extensive epidemiological study, conducted from 2005-2013, found probable links between PFOA exposure and pregnancy complications, such as hypertension, pre-eclampsia, low birth weight, preterm birth, miscarriage, still birth, and birth defects. The study also found probable links to increased rates of diabetes, cancer, thyroid disease, autoimmune diseases, developmental disorders, and Parkinson’s.

A 2019 community health survey of Merrimack, New Hampshire also found higher rates of similar disorders among residents who had been exposed to PFAS, comparing the results of longtime residents to those of newcomers. They found greater health concerns among longtime residents, including cardiovascular and developmental disorders.

In 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry announced a multi-site study of PFAS exposure and health outcomes in Colorado, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Massachusetts, New York, and California. Those studies are still underway.

Without a concerted public effort to address PFAS contaminants, individuals are left to face the problem alone. Boyle pointed out neighbors that live in the contamination zone, who would have every reason to suspect their water is contaminated, but decided not to have it tested. When people ask Oitzinger whether they should get their blood tested, he doesn’t know what to tell them; the tests are costly and doctors may not even know which ones to request or how to interpret the results. And if someone’s blood contains dangerous levels of PFAS, what can they do?

Bad Blood

Since 2017, the community has watched as Johnson Controls and Tyco pushed back against the DNR and—through the Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce—advocated against PFAS regulation while touting the mitigation steps the companies have taken. Oitzinger said every step of the way—whether it’s pushing for more water testing, better signage, or health screenings—local clean-water advocates have been met with resistance.

“We do what we can, but I’m struggling with a company that right now is trying to contain their liability and settle things and … legally get out of town,” Oitzinger said. “So that problem is behind them, that they have no more lawsuits, they have no more expenses, and they just want to say, ‘We fixed it all.’”

In the emailed statement to UpNorthNews, Tyco said its “actions speak louder than words and show our commitment to cleaning up the PFAS that came from our facility.” Tyco added it works closely with the DNR “to investigate and remediate the problem.”

Meanwhile, there is no longer-term solution for families in Peshtigo whose wells are contaminated. Tyco proposed connecting the City of Marinette’s water system to homes in Peshtigo that have contaminated wells (including Lamont’s and Boyle’s), but city and town officials voted against it. Though Tyco offered to cover the initial cost of extending the water, it was unclear whether the company would pay for its operation and maintenance.

Lamont and Boyle have Tyco filtration systems for their well water. But because they are carbon-based, Lamont said, “the [less complex] PFAS compounds are not treated well by carbon… They go right through the system.” Lamont said he now only uses well water for showering and washing clothes. Boyle has also had his filtered water tested and found it still contains PFAS.

Tyco said it is working with state agencies and regional governments to find a long-term solution.

“As a company that has been in Marinette for over 80 years and employed generations of residents, Tyco is committed to the community,” Tyco’s stated. “In fact, we recently invested $11 million in a new Advanced Research and Testing Facility at the [Fire Technology Center], which is part of our effort to develop non-fluorinated firefighting foam, so we can continue to save lives with less impact on the environment.”

With decades of experience in contaminant remediation, Lamont said that even if everything works as planned, there is no quick and easy fix. The GETS system, if it functions as intended, will take an estimated 30 years to reduce PFAS to a safe level in groundwater.

“That’s one of the things I tried to tell people right away, ‘When is it going to get cleaned up?’ This is a long-term deal,” Lamont said. “It’ll be decades before this has been cleaned up.”

Politics

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...