#image_title

#image_title

The governor’s climate change task force pointed to the historically detrimental effects of urban freeways and ports on communities of color in a 2020 report. But his administration is pressing ahead anyway.

As the Wisconsin Department of Transportation (DOT) under Gov. Tony Evers looks to resume a long-planned, $1 billion expansion of a 3-mile section of Interstate 94 from six to eight lanes, some Milwaukee residents can’t help but recall the scars of the past after the state DOT held a virtual public involvement meeting for the project on Tuesday.

“We’re using the same playbook from the 1960s that got us into this mess,” Montavius Jones, a Black Milwaukee resident and development professional, told UpNorthNews the morning after the hearing.

In post-World War II America, the federal Interstate highway system tore through America’s urban cores, demolishing predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods in the process. Interstate construction destroyed as many as 17,000 homes and 1,000 businesses in Milwaukee, disproportionately affecting the city’s Black neighborhoods.

To be clear, the Wisconsin DOT’s current proposed I-94 expansion won’t result in the wholesale destruction of neighborhoods. Fourteen—not 14,000—buildings are slated to be demolished. But to Wisconsinites like Jones, the expansion still reeks of a bygone era.

“It’s quite interesting that it always happens to Black and brown communities,” Jones said. “So it’s, you know, ‘We will sacrifice a couple buildings here, a couple buildings there. Who cares? We’ve got to get these cars through.’”

READ MORE: Evers to Jump-Start an I-94 Makeover in Milwaukee

In a Jan. 26 memorandum, President Joe Biden decried the racism with which the federal highway system was constructed.

“Many urban interstate highways were deliberately built to pass through Black neighborhoods, often requiring the destruction of housing and other local institutions,” Biden said. “To this day, many Black neighborhoods are disconnected from access to high-quality housing, jobs, public transit, and other resources.”

That’s in line with Pete Buttigieg, Biden’s Department of Transportation secretary. Even before his confirmation, Buttigieg explicitly called out the racism burrowed in urban freeway design and said Biden’s administration “will make righting these wrongs an imperative.”

Thinking on interstates has evolved since their construction. Some cities are now working to remove the community-destroying and neighborhood-dividing beasts from urban cores. Milwaukee itself is one of the major success stories, as removing an underutilized and unfinished downtown freeway spur at the turn of the century jumpstarted $1 billion in redevelopment projects that eventually spawned the Bucks’ Fiserv Forum.

Still, critics of the I-94 expansion have pointed to an apparent disconnect between the expansion project and Evers’ own climate change task force, led by Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes, which highlighted the historically detrimental effects of urban freeways and ports on communities of color in a 120-page report. “This results in high exposure to air, water, and noise pollution in these communities, which in turn results in racial health disparities and economic divestment,” the task force wrote in December 2020.

The disconnect is obvious, Cassie Steiner, campaign coordinator with the environmental group Sierra Club of Wisconsin, said in an interview.

“Seeing this project moved forward by the Evers administration, who has expressed so much concern about this climate crisis, is really disappointing and out of line with the administration’s values,” Steiner said.

‘Fix at Six’

There is almost universal agreement that the half-century-old segment of freeway is in need of repair and safety improvements—the crash rate on the stretch is two to three times higher than the state average, and rush hour frequently results in severe congestion—but not everyone agrees expansion is necessary to achieve those goals.

“Improving the safety is really paramount and one of the key things we’re trying to accomplish with the project,” Brian Bliesner, the southeast Wisconsin freeways chief for the state DOT, said during the Tuesday virtual public involvement meeting.

About 250 people viewed the meeting in real time, with several dozen of them asking questions in the chat, such as how the expansion would affect communities of color and whether the DOT would consider simply repairing the freeway.

A handful of commenters started repeating the phrase “Fix at Six” to signify their support for a counterproposal for the state DOT to make repairs and safety improvements without adding two additional lanes.

Some members of the Milwaukee Common Council are also opposing the expansion because of the $1 billion price tag, and because the DOT is relying on traffic and environmental studies from 2016 to inform the current design.

The project was first approved in 2016, but former Republican Gov. Scott Walker pulled the plug in 2017 because he didn’t want to spend state tax dollars in Milwaukee. The Sierra Club, Milwaukee Innercity Congregations Allied for Hope (MICAH), and the NAACP of Milwaukee had also filed a federal lawsuit to stop the project before Walker changed his mind.

The Sierra Club is part of the Coalition for More Responsible Transportation in Wisconsin, which is made up of social justice and environmental groups from around the state, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Wisconsin and MICAH, and opposes Evers’ plan to resume the freeway expansion.

Steiner said she is holding out hope the Federal Highway Administration will halt the project. The administration this month asked Texas to hit pause on a planned interstate expansion in Houston after residents there raised civil rights concerns.

“Repairing at its current six-lane footprint is the best solution,” Steiner said, arguing that it will strike a balance between environmental and racial justice, safety, and economic growth.

Bliesner said the stretch of road would need to see a 25% traffic reduction to justify keeping it at six lanes. Traffic data shows the number of vehicles that pass through the corridor on an average day has fluctuated over the past two decades but not substantially increased. While traffic numbers plummeted in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic, Bliesner said travel has returned to near pre-pandemic levels.

The state DOT’s final design is anticipated this year. If approved, the construction is expected to start in 2023 or 2024 and take three to four years.

UPDATE: The headline of this story has been updated.

Politics

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

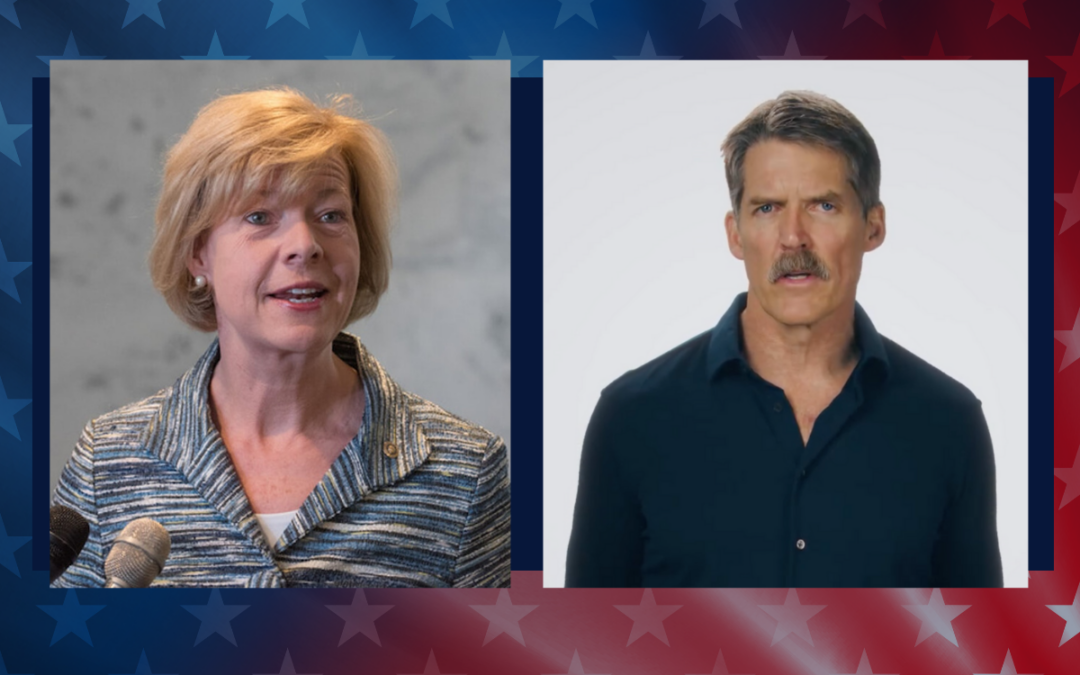

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...