#image_title

#image_title

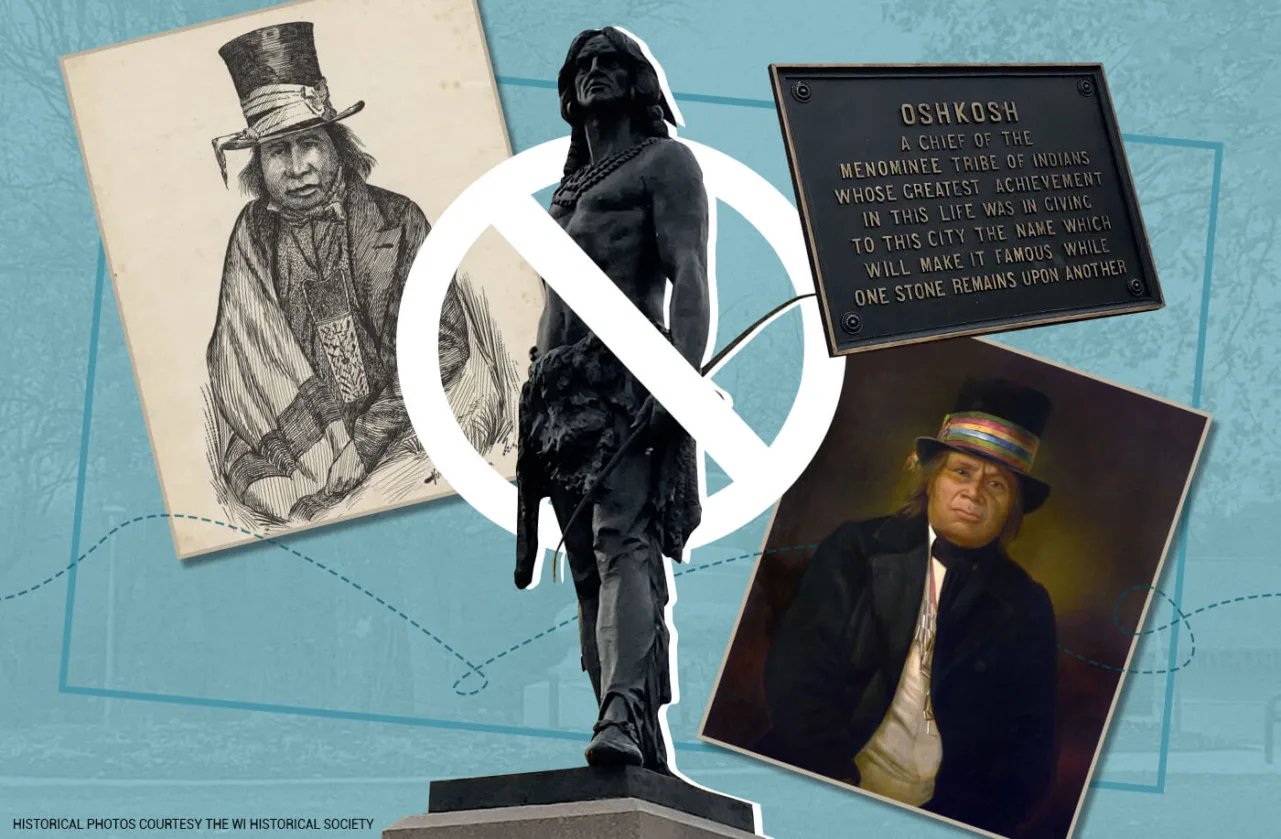

The city of Oshkosh is adding new plaques explaining why its statue of its namesake, Chief Oshkosh, falls short.

There are two major problems with the statue of Chief Oshkosh in the city of Oshkosh right off the bat.

First, the plaque below said that Oshkosh’s great achievement “was in giving to this city the name which will make it famous.” Second, while the statue at Oshkosh is a beautiful statue, it was purposefully sculpted not to look like the real Chief Oshkosh.

Now, Oshkosh officials, members of the Menominee tribe, and scholars are trying to correct the record. They have come together to commemorate the real Chief Oshkosh and his real accomplishments through a series of plaques to be installed in spring 2022 around the statue that will also explain how the statue’s portrayal of a Chief Oshkosh perpetuates harmful stereotypes of Indigenous people.

The assertion that Oshkosh’s greatest achievement was being a city’s namesake raised eyebrows among the Menominee.

“There’s more to it than that,” said David Grignon, tribal historic preservation officer for the Menominee tribe.

Oshkosh was the Menominee Head Chief from 1827 to 1858, and is remembered as a great statesman and leader who negotiated to have his people remain in Wisconsin—albeit on a much smaller section of land—instead of relocating to Minnesota.

“Oshkosh’s legacy is not just giving his name to the city, but it’s the legacy of the Menominee people still alive and those of the past,” Grignon said. “It’s that he was the main chief. And the Menominee reservation—that’s his legacy.”

Not only do the current plaques whitewash Oshkosh’s accomplishments, but the statue intentionally presents an stereotypical depiction of a Native American.

In a letter, the sculptor Gaetano Trentanove wrote that he “wanted to make a statue of chief Oshkosh when he was a real Indian chief before the influences of the white people had affected him at all… to represent the real typical Indian of North America with feathers, deerskin, and moccasins, and not with modern clothes.”

Oshkosh Mayor Lori Palmieri sees the collaboration on the plaques as an important first step for the city and the Menominee to build a mutually beneficial relationship.

“A number of folks can agree that even when we disagree, we can do it in such a way that is healthy and healing,” Palmieri said. “And so I think that has added to our skill set as a community to be able to do that.”

Palmieri, who has a grandson who is part Menominee and is studying natural resources at the College of the Menominee Nation, added, “It’s always interesting to hear different perspectives from the elders and knowledge keepers, as well as the young people.”

She pointed to a collaboration between UW-Green Bay and the Oneida to plant wild rice to sustain the coastline, as an example of how she’d like to see the relationship continue to grow.

“If they would be willing to share that indigenous knowledge, certainly we’re much the richer,” she said.

Oshkosh’s Legacy

Oshkosh was born in 1795 as a member of the Bear Clan of the Menominee—the clan in which the tribe’s orators and statesmen were raised. Before he became head chief, he was a warrior who fought alongside the British in the War of 1812 at Mackinac, Fort Meigs, and Fort Sandusky, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society. He later fought alongside the Americans in the Black Hawk War of 1832.

In 1827, Oshkosh was named head chief of the Menominee just before they and other Wisconsin tribes entered negotiations over their territory with the governor of the Michigan territory and the federal government.

One of the new plaques emphasizes that Oshkosh had to deal not only with encroaching European and American settlers, but also with the “New York tribes”—Oneida, Stockbridge-Munsee, and Brothertown—which had just been displaced by the US Government and were forced to resettle in what is now Wisconsin.

RELATED: Indigenous Chefs Are Ready to Share Their Native Cuisine

In 1840, the US government wanted to create a new state from the Michigan territory—Wisconsin—and so offered to buy the remaining Menominee land and relocate the tribe to 600,000 acres of land along the Crow Wing River in Minnesota. Grignon said the government promised the Menominee lots of resources on the land for them to use, but when the chiefs went to check on the land themselves, that’s not what they found.

Oshkosh decided to travel to Washington DC to petition then-President Millard Fillmore to allow the Menominee to stay in Wisconsin. After two days of negotiations, Oshkosh and Fillmore reached a temporary compromise.

“Oshkosh said, ‘There’s this piece of land on the upper Wolf River that nobody wants,’” Grignon said. “‘It’s called a wilderness. Let me move my people there.”

Chief Oshkosh remained head chief until he died in 1858 on what had become the Menominee’s official tribal territory, which still exists today.

“We lost a lot. We lost over 10 million acres of land,” Grignon said. “We were able to keep a fraction of that and move tribal members onto this new reservation to make the best of what the situation was.”

Tied to the Land

The Menominee relocated to a 235,523 acre island of heavily forested land bisected by the Wolf River and sprinkled with small, interconnected lakes. There, Grignon said, they were able to continue growing wild rice, fishing, hunting, and growing small gardens.

“The Menominees are a forest people,” Grignon said. “We were able to maintain those activities here on the reservation because we’re familiar with this land. It’s several lakes and streams and forest and hunting, trapping, and fishing.”

The Menominee forest has become a model of sustainable forestry practices, which has balanced logging with maintaining a healthy ecosystem. A quote attributed to Oshkosh instructs:

“Start with the rising sun and work toward the setting sun, but take only the mature trees, the sick trees, and the trees that have fallen. When you reach the end of the reservation, turn and cut from the setting sun to the rising sun, and the trees will last forever.”

‘A Real Indian’

Gringnon, fellow Menominee member Arther Chevalier, and UW-Oshkosh professor Pascale Manning, who have been working with the city on the additional plaques since 2018 were at Oshkosh Council Chambers when the city council approved the plaques.

Four out of the five had been fairly uncontroversial, but the fifth plaque, which discusses the problematic framing and depiction of Oshkosh in the original statue and plaque, received some pushback from the Landmarks Commission.

Manning, whose research includes Indigenous literature, said that Trentanove’s depiction of Oshkosh as a “real typical Indian of North America” fits a common trope of Indigenous people called the “Noble Savage,” which she says has been a “mainstay of American popular culture since the end of the 18th century.”

“This is a figure that is a symbol of a glorified pre-[European] contact past,” Manning said. “He embodies a cultural fascination with strength, with exoticism, with mysticism. But in being tethered specifically to an idea of the past, he also embodies something that is passing away, something that doesn’t belong to the present.… He’s a figure who’s always represented as being on the cusp of vanishing.”

Images of Chief Oshkosh, either drawn, painted, or—in one instance—an actual daguerreotype, show that the chief wore western-style clothing, albeit with a Menominee twist: a top hat with a colorful band wrapped across and strings of beads hanging below his necktie. It points to a more complicated picture of how contact with Europeans affected Indigenous communities.

“The figure of the Noble Savage in figuring a pre-contact ideal is never ever expressive of the realities of contact,” Manning said. “You never see traces of contemporary clothing on a figure who fits the characteristics of the Noble Savage because the Noble Savage articulates authenticity as something that belongs to a pre-contact era and identifies any kind of markers of contact as forms of degradation from some pure ideal.”

It’s also a homogenized figure; all Noble Savage figures wear a standardized uniform of moccasins, feathers and deerskin, and don’t display any of the variation between tribes.

Manning said that, by keeping the statue erect and adding the context to it, she hopes to educate people about how these depictions have harmed Indigenous peoples.

“[Trentanove] is very clear that he sees the real Oshkosh as somehow a degraded version of what he would like to reproduce,” Manning said. “And that kind of normalized racism, it carries through.”

Correction: A quote that was erroneously attributed to Oshkosh Mayor Lori Palmieri has been removed and replaced.

Politics

Biden administration bans noncompete clauses for workers

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) voted on Tuesday to ban noncompete agreements—those pesky clauses that employers often force their workers to...

Opinion: Trump, GOP fail January 6 truth test

In this op-ed, Milwaukee resident Terry Hansen reflects on the events that took place on January 6, the response from Trump and other GOP members,...

Local News

Readers Poll: Top Bowling Alleys in Wisconsin

Looking for the best bowling in Wisconsin? Look no further! Our readers have spoken in our recent poll, and we have the inside scoop on the top...

8 Wisconsin restaurants Top Chef judges are raving about

Top Chef’s 21st season is all about Wisconsin, and on-screen, it’s already apparent that the judges feel right at home here. But, while filming in...