#image_title

Few safety upgrades at factory, but $2.6 million in executive bonuses.

Mike Jackson’s family says they still haven’t received a card or a phone call — no sign of condolences from Jackson’s employer, Briggs & Stratton, after the 45-year-old father of eight caught coronavirus, collapsed on the job, and died of the virus.

“His fiancee, they haven’t heard anything from the company, we haven’t heard anything,” said Ed, Jackson’s older brother who lives in Milwaukee, used to talk to his brother every day, and is regularly in contact with Jackson’s fiancee. “Never called to see if he’s OK. They never called to see how he was doing, none of that stuff.”

Jackson was yet another essential worker who died during the pandemic. Such workers, more likely to be people of color working close-quarters, low-wage jobs with little or no sick leave, have been infected with coronavirus at alarming rates. At the same time, many companies are refusing to release the number of employees who have tested positive for the virus, leaving surrounding communities — and at times, their own employees — in the dark.

Coworkers and family say Jackson had exhibited coronavirus symptoms for weeks but felt pressured into working sick because Briggs & Stratton does not provide sick leave or hazard pay, and pays $375 per week for workers who voluntarily quarantine, as confirmed by the company. Briggs & Stratton did not respond to questions about whether the amount would be raised or if the company would start to offer paid sick leave.

Meanwhile, the company doled out $2.6 million in bonuses to its executive board this month, including a $1.2 million payout for its chief executive officer Todd Teske, according to a June 15 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Jackson was sent home on May 14 because he was not feeling well. He then came in for mandatory overtime before being sent home again on May 16, and finally collapsed before being hospitalized on May 18, according to Chance Zombor, a grievance representative with United Steelworkers Local 2-232, which represents Briggs employees.

“He was falling, collapsing at the line,” Zombor said.

Jackson never came back. He died on May 28.

“There’s a disadvantage to a hard worker,” said Tony, Jackson’s younger brother. “If you look at someone like my brother, no matter what he’s going to go in and work. But if the company don’t appreciate or take care of their employees, what can they do? It leaves them in a situation of, do I go to work … or do I stay home and get fired? How are you going to take care of your family?”

‘Too little, too late’

There is no indication that Briggs & Stratton, a Wauwatosa-headquartered small engine and lawn mower parts manufacturer, has taken meaningful steps to prevent another death like Jackson’s. Employees must now take temperature tests when they start their shifts and the company has provided some hand sanitizer, taped the floors to encourage social distancing, and installed some plastic barriers (“where social distancing is more difficult,” the company told UpNorthNews), but workers are still on close-quarters assembly lines.

Rick Carpenter, vice president of corporate marketing and communications for Briggs & Stratton, wrote in an email to UpNorthNews that “we are doing quite a bit to keep our employees safe in trying to combat this virus.”

He said the company is “in concert” with guidance from OSHA, the Centers for Disease Control, and the Wauwatosa Health Department.

Carpenter also said Briggs has “a very clear” Pandemic Safe Worker Handbook but did not respond when UpNorthNews asked for a copy. Zombor responded, “I don’t know what that is. I’ve never seen that. Nobody knows what that is.” He said the closest thing to a handbook he has seen is three or four information sheets about hand washing and social distancing posted on a bulletin board.

Employees contest the assertion that Briggs has done enough to protect them.

“It’s too little, too late,” Zombor said, calling the company’s efforts “cosmetic changes.” Even with temperature tests, he pointed out, employees may show up and spread the virus while asymptomatic.

In late April, the company handed out five masks to its workers, said Herbert Williamson, a Briggs employee of five years and Jackson’s cousin. When employees got ahold of the masks, Williamson said, it seemed to be a joke.

“If you looked at them, they looked like someone sat down and just cut a mask out of a T-shirt,” Williamson said.

“They were like single-ply fabric masks,” Zombor said. “People were making fun of them when they got them. You could put them on and blow out a match. People felt like it wasn’t actually giving them any protection.”

There is still no requirement to wear masks, according to Zombor and Williamson. The company has made it clear that it will not require mask use, Zombor said, even though he has requested it. Carpenter did not answer a question about whether the company would reconsider that policy.

“You’ve got employees in there that are actually scared,” Williamson said. “They’re terrified.”

That feeling has been exacerbated by the company’s lack of compassion, even in the face of its own employee dying, Williamson said. He said it is common knowledge in the workplace that Jackson was Williamson’s cousin, but only one supervisor from a different department showed him any sympathy.

“My own supervisor didn’t tell me anything until I asked her for a personal day to take off for Michael’s funeral,” he said. “That was only days before his funeral, and everyone in the building knows that me and him is related.”

In an email to UpNorthNews, Carpenter offered “our thoughts and prayers — from all of us at Briggs” to Jackson’s family.

On April 21, days before the masks were distributed, Jackson and a few of his immediate coworkers walked off the assembly line to speak with management and demand better worker safety. Zombor said the company accused Jackson and his coworkers of engaging in an unauthorized strike “and coerced them back to work.”

Just over a week later on May 1, Briggs & Stratton issued a press release boasting of how it is playing a role in manufacturing reusable masks for frontline workers. The release said Briggs “continues to be humbled by the heroic acts of the healthcare professionals who are working on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“They’re making these masks and bragging about it to sell,” Zombor said. “And meanwhile their own workers are working side-to-side, face-to-face with no protection.”

Through all of this, the company has not disclosed to its employees how many workers have tested positive for COVID-19, nor where they work in the factory, according to Zombor and Williamson. Zombor said in a call with Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the company claimed it had 12 cases, but he thinks the true number is much higher.

Jackson’s line was temporarily closed after his death, Carpenter said. Zombor said it was only because so many people went on voluntary quarantine that the line could not have continued operation.

Carpenter did not answer when asked how many employees had contracted the virus.

“It’s only a matter of time before even more people die or more people come forward,” said Adebisi Agoro, Jackson’s younger cousin. Jackson’s family plans to pursue legal action against Briggs, Agoro said.

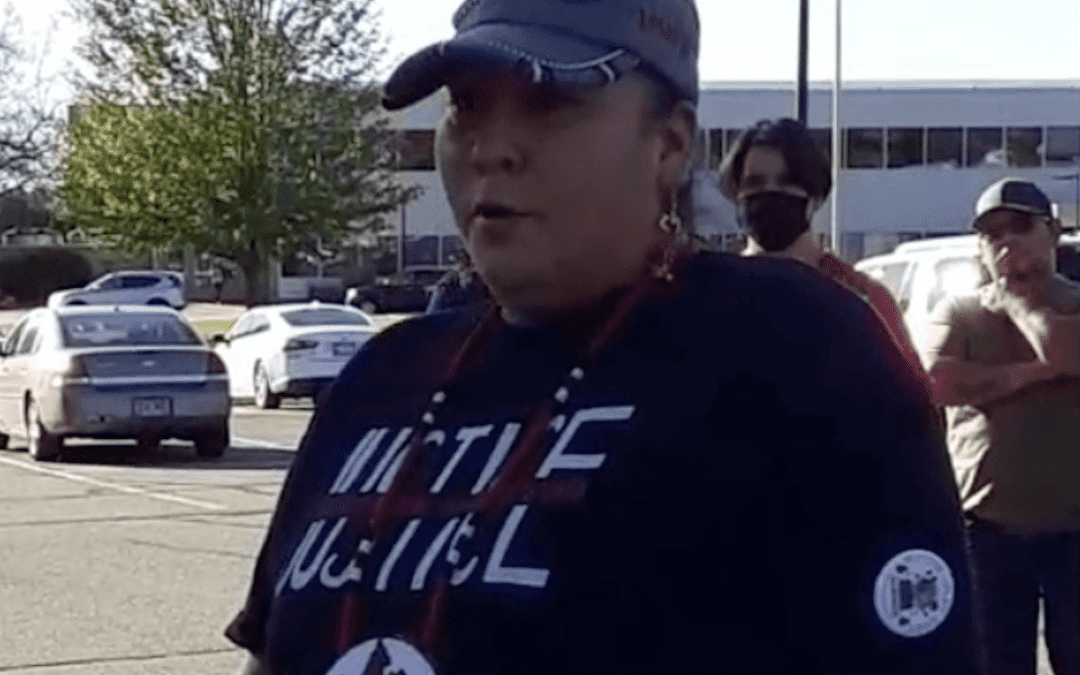

Agoro participated in two press conferences, hosted by worker and immigrant advocacy group Voces de la Frontera, regarding Jackson’s death. After the second, a caravan of protesters made its way to Assembly Speaker Robin Vos’ house to urge the Legislature to take action to protect workers.

Vos, who has only convened the Legislature once during the coronavirus pandemic, has remained silent when faced with such calls. Minutes after the protesters laid a wreath and photos of Jackson and an essential worker who died in Vos’ hometown of Burlington, the Speaker had the memorial removed from his property.

Agoro compared corporations’ and politicians’ indifference toward essential workers to the treatment of enslaved people.

“It’s just like that same care,” he said. “They probably cared for slaves better than they cared for essential workers, damn near,” he said, describing the workers as being treated like they are disposable. “It’s a temp worker working my cousin’s job right now — not even a permanent worker.”

The fight has seemed hopeless at times. Agoro and Zombor said the only way they could see meaningful change is if workers stop depending on lawyers and politicians and band together instead.

“They can keep replacing people,” Agoro said. “We are the new expendable product.”

Editor’s Note: Since publication, this story adds further details about Ed Jackson’s daily contact with his brother and his brother’s widow, details about how the company responded to questions posed by UpNorthNews about quarantine compensation, sick leave, and a pandemic handbook, and clarification about Mr. Agoro’s comparison to enslaved workers.

With Afghan Refugees, Wausau Gets Chance to Show Welcoming Side After ‘Community for All’ Controversy

Wausau will take in as many as 85 Afghan refugees who fled the Taliban takeover of their home country. Wednesday’s announcement that as many as 85...

Native American Leaders Seeking Improvements to Curriculum After Teacher Wears Racist Outfit

Insensitive depictions of Native Americans are demeaning and further negative views that help lead to violence against indigenous people, advocates...

Commentary: Little Has Changed Since the Blake Shooting. It Doesn’t Have to Be That Way.

Despite immense pressure for change, political leaders have done little. Activists have stepped up. One year ago today, in the throes of a...

Commentary: Cedarburg’s School Mural Fiasco Shows Why We Need to Get Out of Our Bubbles

The district said the mural didn't represent "all members of our school community." But who was really left out? Earlier this month, the Cedarburg...