Image via Shutterstock

Early legal challenges upheld the taxpayer-funded program back when it was small and experimental, not the expensive statewide behemoth it is today.

Earlier this spring only 60 percent of the funding referendums by Wisconsin Public School districts were approved. Every year more districts apply for additional financial aid to help struggling education budgets but the approval rate remains low, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum. Meanwhile, taxpayer-funded voucher institutions continue to expand and siphon more money away from public schools that are experiencing declining enrollment and educator and staff shortages.

Private school critics have questioned the constitutionality of the program several times in an attempt to shut it down and divert resources back to public schools—most recently in a request last year to have the Wisconsin Supreme Court take up a challenge directly. Recent lawsuits in Arkansas, South Carolina, and Utah have also questioned the legality of vouchers. Public education advocates are concerned private institutions cannibalize taxpayer funding.

The complaint filed last October by lead plaintiff Julie Underwood, Dean Emeritus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and six others (a case funded initially by the Minocqua Brewing Company SuperPAC) claimed the funding legislation for private schools is unconstitutional because it places voucher institutions in an unfair financially advantageous position in comparison to public schools. When a student leaves the public education system for a voucher school, district funding decreases by a disproportionate amount. As the voucher program grows, more students leave the public program, taking funding away from already struggling districts.

Public school advocates also argued that public money should only be used for public purposes and not for private schooling. The petition for direct action was denied by the justices, meaning the case must first be heard by lower and appeals courts.

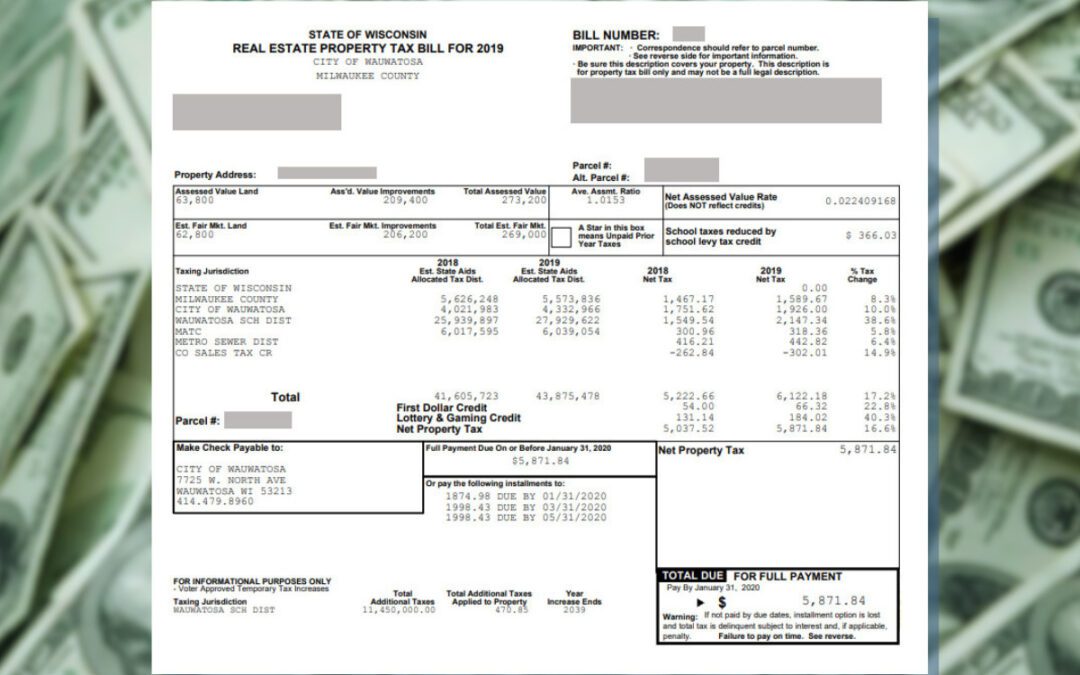

Public school finances are also hamstrung by caps on taxpayer funding that were arbitrarily placed by the Republican-controlled Legislature in 1994. School boards, already elected by local voters, must go back to voters with a referendum any time they seek to raise taxpayer funding beyond the caps. . The McFarland School District, for example, asked voters in April to exceed the caps by $10.6 million over five years, but it did not pass.

“Our neighbors have successfully passed referendums,” said McFarland superintendent Aaron Tarnutzer. “In our geographic area we are one of the few that have not passed. And the challenge for us is, how do you stay competitive with attracting and retaining employees, when you aren’t compensating your staff at the level of those districts that are able to compensate more, because they passed an operational referendum?”

The McFarland district is expecting a $2.5 million deficit for the 2024-2025 school year. If the budget target isn’t met, the district will have to cut staff. Its schools are experiencing teacher shortages, difficulty attracting new staff, and trouble covering rising operational expenses. In McFarland the teacher pay is below average when compared to nearby school districts. Compensation, workload, and work-life balance were the top reasons why teachers left, according to the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

“Lastly, another financial concern is growing student needs. So even before the pandemic we saw increasing student needs primarily related to mental health. That was exacerbated during and following the pandemic. It was impacting our ability to instruct students. So, at a time where you’re under financial constraints and don’t have the funds to hire new staff, it’s somewhat of a perfect storm of challenges,” said Tarnutzer.

This year’s state aid increase of $325 per pupil spending is criticized by many educators as insufficient and far from covering inflation, much less ongoing costs. They say the amount would have to be more than doubled to fully cover essential expenses. For the past few years it has relied on federal pandemic relief. The funding is no longer available and will not be backfilled by the state.

“The state gave much greater increases to voucher schools and independent charter schools in the last legislative session than they did to the public schools,” said Underwood. Public schools haven’t had an inflationary increase in funding since 2010.”

Early court challenges determined that school vouchers could continue to be funded with taxpayer money as long as the public system was adequately funded in 1992. Back then the program cost less than public schools to educate students. Today the taxpayer money required to keep the choice programs running has risen 22,500%. By 2026 the student enrollment cap for the private system will be gone. The programs will be able to grow without limit and will drastically defund public schools.

“The Legislature says that they’ve provided historic investments in public education. Well, that’s just not true. Because we have spending caps for the public school funding formula and unless the government increases it, what happens is you can’t spend the leftover money. It just gets funneled back out in the form of property tax relief and they have provided a lot of property tax relief,” said Underwood.

Voucher schools have been legally challenged several times. The first lawsuits that questioned the constitutionality of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP) were in the 1990s. The program was ruled unconstitutional in 1992 because it violated the mandate that schools have to provide free education. Five years later a state constitution amendment allowed students to use vouchers for private religious schools. Then in the 1998 case Jackson v. Benson opponents claimed the institutions violated a state requirement that banned the use of public money to benefit religious seminaries.

As in Wisconsin, voucher programs in Arkansas, South Carolina, and Utah have faced similar criticism. Last month, Arkansas filed a lawsuit asking the state to block the voucher program’s enforcement. The complaint contended that choice schools violated the state’s constitution by using public funding for private institutions. In South Carolina and Utah, plaintiffs filed complaints with similar arguments in 2023 and 2024. The latter document states taxpayer money should not be used for “exclusive, admissions-based private schools.” The state constitution emphasizes that education should be free and open to all and not controlled by sectarian rule.

Administrators and educators in all four states are concerned vouchers will drastically drain public school resources. The growing number of students joining private institutions requires choice schools to request more taxpayer money, which takes away from public education resources.

Additionally, the institutions are not overseen by the state or federal government and are not required to protect the legal rights of students, according to the complaint documents. They have been accused of excluding students based on disability status, religion, or gender identity.

“The whole point of the Republican Legislature is that these private schools should be completely unregulated,” said Underwood. “All of the rules for public education don’t apply to the private schools. And the reason that private is better is because it is unregulated by the government. They have protected the independence of the private schools.”

Here’s the real reason your property tax bill is likely much higher — and it’s not ‘the 400-year veto’

It’s not about greedy school boards, it’s about a Legislature literally passing the buck. Everyone would like a big year-end bonus—the kind Clark...

Virtual learning growing in Wisconsin, school leaders say

After eight hours of training at the Milwaukee Ballet Academy, Cecilia Smucker logs onto her laptop for four hours of online learning through...

WI teacher: Federal special-ed cuts another blow to struggling state

By Judith Ruiz-Branch A Wisconsin teacher is voicing significant concerns about the recent federal special education cuts and says it’s an...

Wisconsin public school enrollment declines continue as vouchers grow, new data show

Enrollment in Wisconsin's public school districts has continued to fall, while other types of schools are gaining students, according to the state's...