#image_title

Redistricting expert calls the proposed maps a “good-faith effort,” though they need some work to comply with the Voting Rights Act.

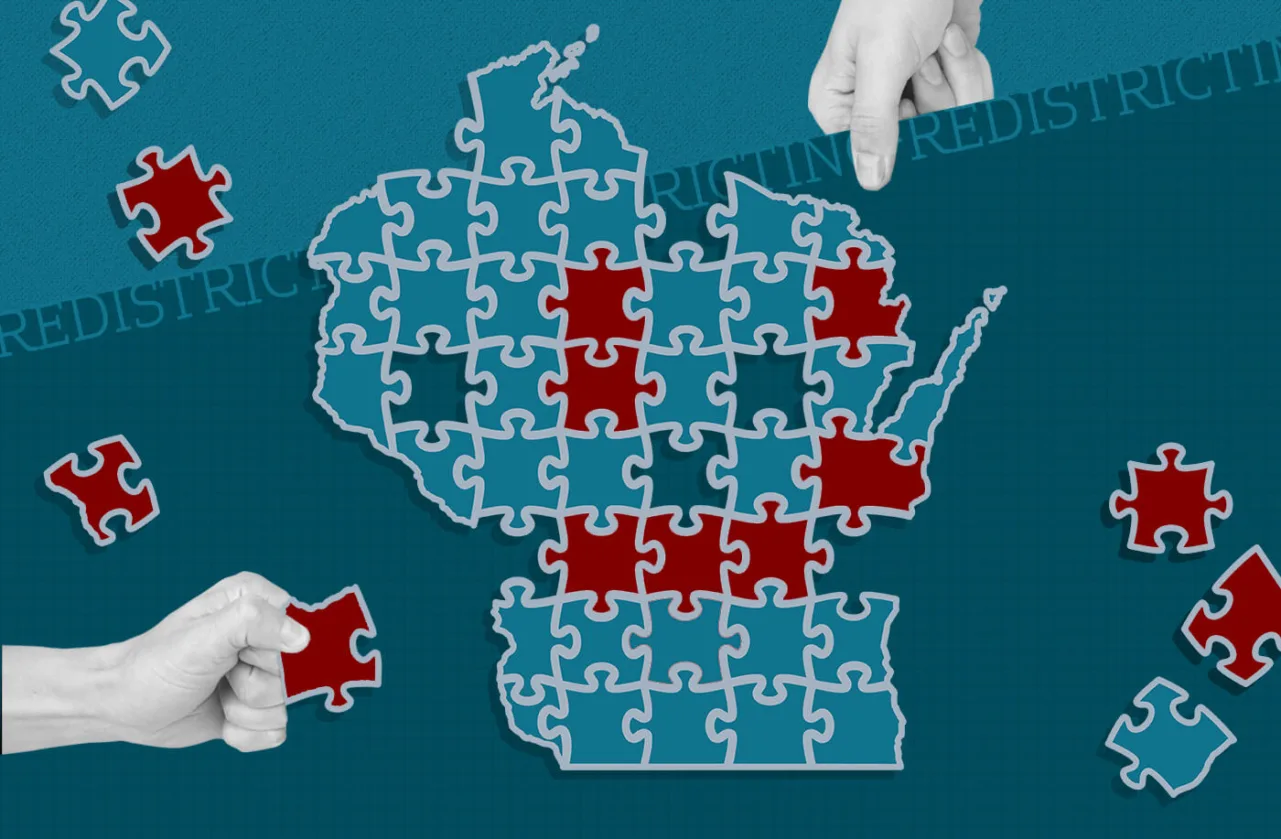

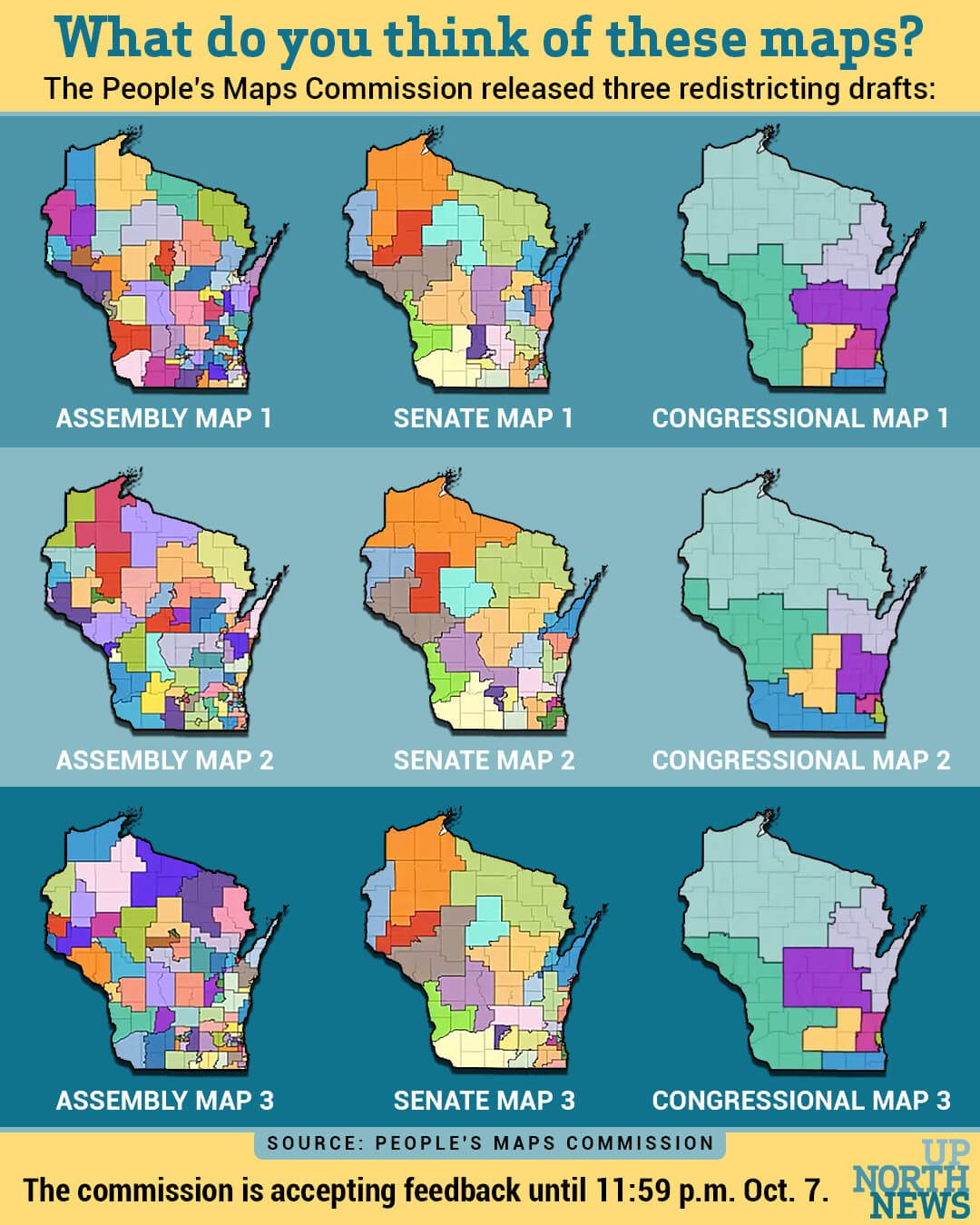

The People’s Maps Commission, which was created by Gov. Tony Evers to redraw Wisconsin’s electoral maps in a fair and impartial manner, released three proposed maps on Thursday evening.

The proposed maps were released as the state moves closer to implementing new district boundaries for the state Assembly and Senate and US House. Republicans in 2011 drew maps that included oddly shaped districts to give themselves a locked-in majority in the Assembly, Senate, and House, a process called gerrymandering.The public is invited to look at the nonpartisan commission’s draft maps at portal.wisconsin-mapping.org/plans and provide feedback at portal.wisconsin-mapping.org/ up until 11:59 p.m. on Oct. 7.

Commission Chair Chris Ford said the commission will revise the maps based on the feedback they receive and make a final decision in the next few weeks about which map they want to endorse.

Moon Duchin with the MGGG Redistricting Lab at Tufts University, who has been working with the commission, said Republicans still would retain an advantage in the Assembly, but it would not be as stark as the current maps.

Duchin’s analysis, which used data from the last 14 elections, found that the maps were “responsive” and more seats would fluctuate between the two parties. Duchin commended the commission for maps with competitive districts “that don’t always lock in an advantage for one party or the other.”

An analysis by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel found that with an evenly split ticket at the top, Republicans would still have a 55 to 58 seat advantage over Democrats under each of the three maps drawn by the People’s Maps Commission.

‘It’s Not Easy to Balance’

Robert Yablon, a law professor at UW-Madison and redistricting expert, called the commission’s maps a “good-faith effort” and said that, according to several metrics, they are more fair than the current 2011 map: They have less partisan bias and more competitive districts, resulting in more seats potentially changing hands between the two parties.

“There are still going to be a fair number of seats that are safe for one party or another. That’s just a function of geography,” Yablon said, referring to how Democrats tend to live in cities and Republicans live in rural areas. “But they may see if there are ways that those maps can be made even more equal politically without sacrificing some of the other criteria.”

But an analysis from WisPolitics Friday morning found that the commission’s maps may raise concerns about minority representation, particularly in the state Senate. Two of the state Senate maps only have one majority-Black district; the remaining map has none. None of the maps have a majority-Latino Senate district. The federal Voting Rights Act requires “minority opportunity districts” to ensure racial minority groups have a chance at fair representation.

State Sen. Lena Tayler (D-Milwaukee) said that she shared similar concerns with the proposed Milwaukee County redistricting map, which was also drafted by a nonpartisan group. Taylor and several others raised concerns that the new map could reduce the chances of Black candidates getting elected.

“My first response to the People’s Maps [Commission’s maps] are the same as my response to the county’s maps: that there are some other things that nonpartisan groups might not think about that have to be thought about when you go to draw maps in order to make sure that we are protecting voters’ rights and that we are adhering to the voting rights act,” Taylor said.

RELATED: GOP Approves Resolution That Tries to Lock in Gerrymandering for Another Decade

Taylor is one of three current Black state Senators, with Sen. LaTonya Johnson (D-Milwaukee) and Sen. Julian Bradley (R-Franklin). When she was first elected, she was only the fifth person of color elected to the state Senate and the second woman of color.

“I have always found it important to use my voice, to make sure that we understand the importance of having that kind of diversity in the room,” Taylor said.

Taylor is not the only critic of the commission’s maps. Common Sense Wisconsin, a conservative organization also undertaking redistricting using the state’s 2002 map as its baseline, also released its version of the maps on Thursday. On Twitter, Common Sense said the commission had “omitted the Voting Rights Act from its criteria” and “no plan that ignores the [Voting Rights Act] with only a vague promise to get to it later can be taken seriously.”

Taylor doesn’t want to discard the commission’s work, but the revisions need to incorporate voting patterns, socioeconomics, special interest groups, and where incumbents live to ensure voters of color will have a shot at electing representatives from their communities.

“It’s not easy to balance all of these things when someone is doing this job and so I commend the people who are part of the commission for the work that they’ve done,” Taylor said. “You have to take those other things into consideration because those are realities of what influences elections.”

She gave the example of a Milwaukee County supervisor race in a majority-Latino district where a candidate won all the Latino wards, but because turnout was higher in the wealthier, non-Latino wards, that candidate did not win the seat.

“Those wards literally outweighed the voice of the majority of individuals in the district,” Taylor said. “An individual who was not a Hispanic candidate ended up winning.”

Yablon said the Voting Rights Act does not require majority-minority districts; it does require “fair opportunities for politically cohesive minority groups to elect their preferred candidates.” What that actually looks like depends on the district.

“If you have a district that is 40% Black or 40% Latino, and it’s politically cohesive [those communities tend to vote for the same candidates], then they may elect their preferred candidates, even if they don’t have a majority, as long as there’s some crossover vote from white voters who also favor those candidates,” Yablon said. “It’s a functional analysis that you need to do to ensure that there are adequate opportunities and to ensure that minority votes aren’t diluted.”

Taylor pointed out that Wisconsin does not have a long history of electing candidates of color, and it’s even rarer for one to be elected in a majority-white district. In 2020, Bradley bucked the trend when he was elected by the 28th Senate District, which includes Franklin, Muskego, and Big Bend, as the first Black Republican state Senator in Wisconsin. But again, Bradley is the exception.

“I don’t find that to be acceptable, to not have people of color [in office] at a time where our state is growing both in the urban center with people of color and in rural Wisconsin,” Taylor said. “This is a time that we should not be diluting minority voices, but we should be making sure that those voices are able to be at the table.”

Sachin Chheda, director at the Fair Elections Project, who has been pushing for the Legislature to take up the commission’s maps, also does not believe in throwing out the baby with the bath water. Instead, the fact that the issue was caught before the maps were finalized and can still be changed is, in his opinion, testament to the process.

“This moment reinforces the importance of an open, transparent, and iterative process that includes substantial public comment,” Chheda said. “We will be sharing our specific concerns about these maps with the commission, and we encourage members of the public to do so as well, so these maps can be the best representation of the will of the voters.”

Opinion: Many to thank in fair maps victory for Wisconsinites

On February 19, 2024, Governor Tony Evers signed into law new and fair state legislative maps, bringing hope for an end to over a decade of...

Opinion: Empowering educators: A call for negotiation rights in Wisconsin

This week marks “Public Schools Week,” highlighting the dedication of teachers, paras, custodians, secretaries and others who collaborate with...

Op-ed: Trump’s journey from hosting The Apprentice to being the biggest loser

Leading up to the 2016 election, Donald Trump crafted an image of himself as a successful businessman and a winner. But in reality, Trump has a long...

Not just abortion: IVF ruling next phase in the right’s war on reproductive freedom

Nearly two years after the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, another court is using that ruling to go after one of the anti-abortion right’s...