#image_title

“I think that we should ask Wisconsinites: Think about why very few people know this history when this is not hard to find.”

When Dr. Carter G. Woodson founded Negro History Week in 1926, which later evolved to today’s Black History Month, white historians argued that Black Americans had no history worthy of scholarship. In light of that erasure, Woodson devoted his life to studying and teaching Black history.

Now, as Black History Month moves into the 21st century, historians are noticing a different type of erasure. In Wisconsin, the state’s Black history mainly focuses on its progressive history: abolition, the underground railroad, and, more recently, the Great Migration of Black people from the South to southeastern Wisconsin.

“I think Wisconsinites, like most Midwesterners, think that there’s no history of racism to overcome in the Midwest or in Wisconsin. Or, if there is, it’s really recent,” said Christy Clark-Pujara, associate professor of history and Afro-American studies at UW-Madison. “And it just simply isn’t true.”

Wisconsin’s relationship with its Black communities is long, layered, and, in a word, complicated.

Slavery in Wisconsin

Black people have been in modern-day Wisconsin since 1725 when they were enslaved and brought to the state with French fur traders. And despite the Northwest Ordinance, which banned slavery north of the Ohio River from 1787 to 1875, enslaved Black people were brought by some of the state’s founding fathers.

“The ban on slavery in the Northwest Territory wasn’t worth the paper it was written on in practice,” said Clark-Pujara. “People were violating the law and as long as the people in their community didn’t object to it, they did it.”

Eugene Tesdahl, an associate history professor at UW-Platteville, pointed out that race-based slavery goes back even further than 1725 to the French fur traders who enslaved Indigenous people before bringing enslaved Black people to the territory.

Many lead prospectors, who came from slave states like Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee, assumed that, like in other northern territories, white people in Wisconsin would look the other way instead of enforcing the territory’s anti-slavery law. So they brought their enslaved Black people up North and built their fortunes off of the free, forced labor.

Among those prospectors was Wisconsin’s first territorial governor, Henry Dodge, who had promised his slaves that if they would go with him he would set them free in five years. He finally did it after 12.

“Henry Dodge had enslaved people bringing up 2,000 pounds of lead a day and making tens of thousands of dollars every month exploiting their labor, and it was basically ignored by the authorities,” Clark-Pujara said.

From the 1820s until the mid-1840s over 100 Black people were enslaved in Wisconsin.

“I think that the way that we were taught, and I include myself in this because I received the same colonialist history that everyone else did, is that the Northwest Territories were free of slavery,” Clark-Pujara said. “That’s where people enter their understanding of midwestern history, and that in and of itself has posed a problem.”

What many Wisconsinites learn about in the state’s public schools is the state’s refusal to enforce the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act (on the grounds of state’s rights) and the underground railroad. Clark-Pujara points out that while those stories are true, they’re “not singularly true.”

“It makes white people feel good,” she said. “If you go to small towns throughout the Midwest, everybody claims that their grandma or their neighbor was a stop on the underground railroad. If there were that many stops, there wouldn’t have been an enslaved person left in the South. It’s a story people want to believe.”

The historical erasure of Wisconsin slavery also diminishes knowledge of Wisconsin’s freed Black people who helped build the state. Many of them also made their living, and in some cases their fortunes, at lead mining.

William Maxwell, a freed Black man, owned a lead mine in Platteville where he employed both white and free Black miners until he died of smallpox in his 40s. James D. Williams, another freed Black man, found his fortune first as a miner then bought his own mine in the 1870s where he employed mostly free white laborers.

Tesdahl said that both stories need to be told: the enslavers who ignored territory law and enriched themselves with slave labor and the free Black entrepreneurs who lived, worked and made a life for themselves.

“Both of those stories are really vital pieces of history for all of us to remember,” Tesdahl said.

Black suffrage

While there were opportunities for Black Wisconsinites to make a living, state lawmakers denied them full citizenship by blocking Black suffrage.

The 1846 draft of the state’s constitution would have given Black people the right to vote through a state-wide referendum. But, the version that was ultimately adopted in 1848 only granted the right to vote to white men, native-born men, immigrant men who’d declared their intention to become citizens, and Indigenous people who were US citizens.

Which, Clark-Pujara pointed out, was a high bar in 1848, “as most Native Amerians were considered outside of the nation and couldn’t qualify for citizenship.”

The citizenship requirement of course did not apply to white men.

“You could be a foreign-born white man who resided in the state for a year and vote, but if you were a Black man who was third generation, you couldn’t vote,” Clark-Pujara said.

What’s especially galling to Clark-Pujara is that these documents are all publicly available, and yet many Wisconsinites are unaware of this history.

“They’re not in a shoe box in somebody’s grandma’s attic and nobody knew about this secret diary. They’re accessible,” she said. “I think that we should ask Wisconsinites: Think about why very few people know this history when this is not hard to find.”

Black men finally won the right to vote after Ezekial Gillespie, an abolitionist and community leader, sued the state’s board of elections for the right to vote. The case went all the way to the state Supreme Court. Gillespie won, though Clark-Pujara pointed out that was because there was a technical issue with the referendum against Black suffrage.

“He doesn’t win because there’s a change of heart in Wisconsin about Black men voting,” she said.

Open questions

Clark-Pujara said the history of Black Americans and other communities of color in the American Midwest is a growing area of research because there are so many missing pieces.

“I was looking for the book on the history of Black people in early Wisconsin, and I didn’t see it,” Clark-Pujara said. “As a historian and as a scholar, that became my next project—and that’s what I’ve been working on for a number of years.”

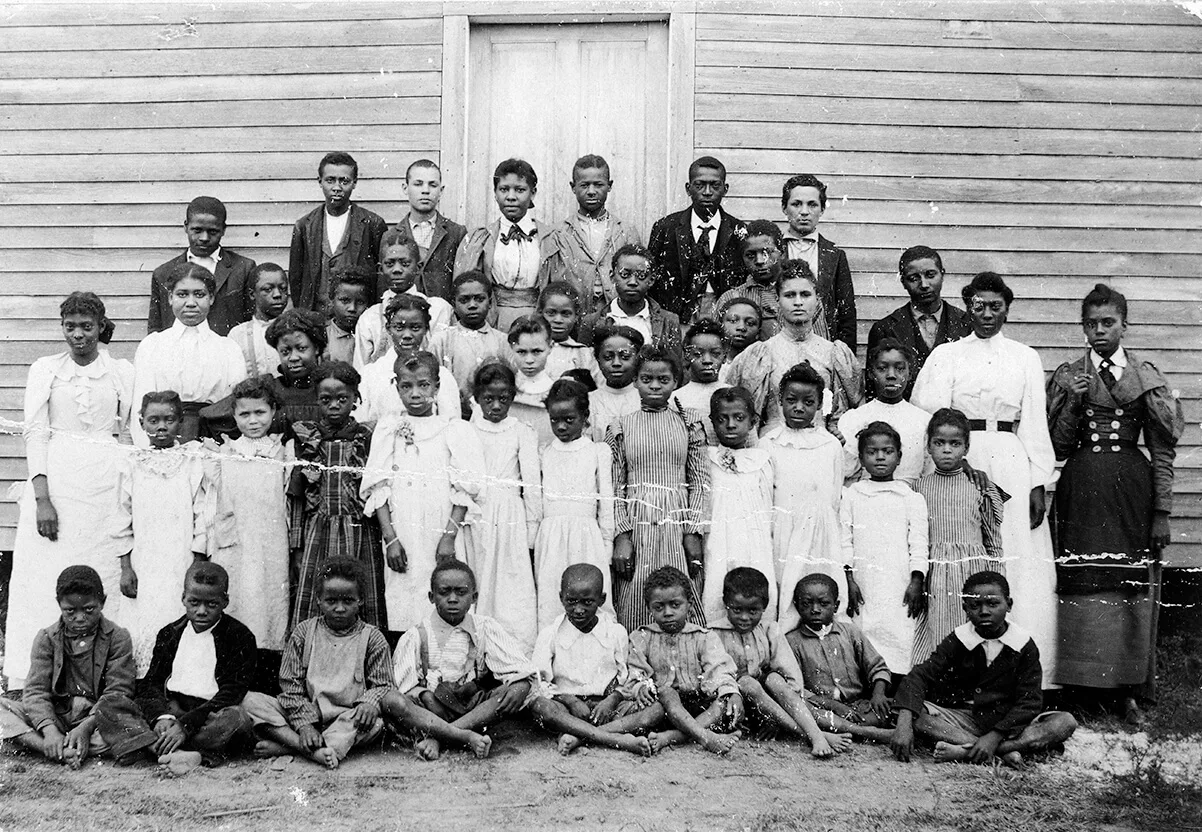

Tesdahl pointed to the incomplete history of rural communities with sizable Black populations, including Freedom; Cheyenne Valley, near Hillsboro; and Pleasant Ridge, near present-day Beetown. Tesdahl said there’s more research to be done on these communities and why Wisconsin’s Black population has migrated away from rural, agricultural settings.

“There was a lot more ethnic diversity than one might assume in the 1840s in rural Wisconsin than by the 1940s,” Tesdahl said.

Researchers have revisited many aspects of the United State’ racist past that have caused communities to question their own local history.

In 2017, sociologist James Loewen published his book, “Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism,” which told the stories of neighborhoods where Black people could be arrested or killed if they were there after dark.

Loewen’s website lists several possible but unconfirmed sundown towns across the country, including in Wisconsin, and instructions on how to confirm any suspicions. The author has prompted communities—including La Crosse, Manitowoc, and Janesville—to explore whether they had been a sundown town.

Clark-Pujara said when she started working on her book four years ago, there were about nine books on Wisconsin Black history, but the field of study has exploded in recent years.

“I’ll barely scratch the surface because there is so much to do,” Clark-Pujara said. “There’s so much that hasn’t been told.”

New Biden rules deliver automatic cash refunds for canceled flights, ban surprise fees

In the aftermath of a canceled or delayed flight, there’s nothing less appealing than spending hours on the phone waiting to speak with an airline...

One year on the Wienermobile: The life of a Wisconsin hotdogger

20,000+ miles. 16 states. 40+ cities. 12 months. Hotdogger Samantha Benish has been hard at work since graduating from the University of...

Biden makes 4 million more workers eligible for overtime pay

The Biden administration announced a new rule Tuesday to expand overtime pay for around 4 million lower-paid salaried employees nationwide. The...

‘Radical’ Republican proposals threaten bipartisan farm bill, USDA Secretary says

In an appearance before the North American Agricultural Journalists last week, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Secretary Tom Vilsack...