#image_title

#image_title

The redistricting process will almost certainly end up in court. A Republican-backed proposal would automatically send all cases to the state’s conservative-controlled high court.

After Republicans argued Thursday morning at the state Supreme Court in favor of a court rule change that could lead to continued partisan gerrymandering in Wisconsin, the nonpartisan People’s Maps Commission continued its quest to create fair maps.

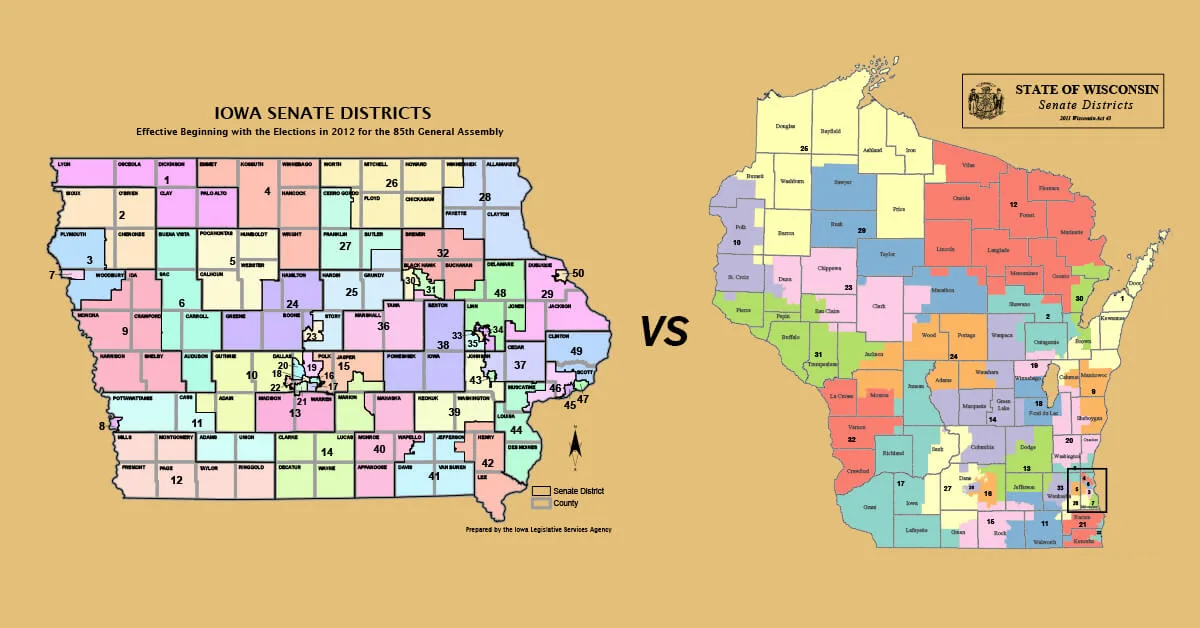

The clashing events, separated by about six hours, served as further foreshadowing of the looming legal battle over the state’s political redistricting. The statewide map-drawing process, done once every 10 years to coincide with the United States Census, sets boundaries for state Assembly and Senate districts, as well as Congressional districts.

With Democratic Gov. Tony Evers in office, legislative Republicans will be forced to either work with him to draw maps he is willing to sign, or go to court. But at the state Supreme Court, a who’s-who of Wisconsin conservatives is trying to get the justices to agree to a proposed rule change that would make the state’s conservatiuve-controlled high court automatically take on any lawsuits centered on redistricting.

The proposed new rule would mean cases challenging new district maps would leapfrog lower courts, theoretically giving the conservative-controlled Supreme Court the ultimate power to set political boundaries. The cases could be filed even before any maps are drawn.

Justices heard arguments in favor of the rule change from the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty and former Republican Assembly Speaker Scott Jensen, and attorneys representing Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, new Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu, and Wisconsin’s Congressional Republicans.

But justices who questioned supporters of the change were highly skeptical. Even conservative Chief Justice Pat Roggensack, who voted to overturn the presidential election, was dismissive of the idea, saying the change would make the court a proactive body, rather than reactive.

“We don’t look out about Wisconsin and say, ‘Oh, something’s going wrong. Oh, we better step in there and fix it,’” Roggensack said. “We determine cases and controversies that are brought to us.”

Roggensack further criticized the idea, saying, “I don’t know how in the world you think the court could ever draw the maps.”

Misha Tseytlin, the state’s former solicitor general under Republican Gov. Scott Walker, argued in favor of the rule change on behalf of Republican US Reps. Tom Tiffany, Bryan Steil, Mike Gallagher, Scott Fitzgerald, and Glenn Grothman.

Tseytlin said if a case reaches the Supreme Court, it would be in the state’s best interest for the court to draw new maps while making the least amount of changes possible, a move that would lock in Republicans’ nation-worst gerrymander for another decade.

Tseytlin said current maps are more “democratically accountable” than theoretical court-drawn maps because they were previously drawn by elected representatives.

“You read a lot of these words like ‘fair maps’ [or] ‘fairness’ but that kind of buries the lead,” he said.

But Tseytlin did not address the fact that Wisconsin’s current electoral districts are anything but “democratically accountable,” according to findings by the Harvard Electoral Integrity Project. The project scores the democratic integrity of Wisconsin’s maps as just 3/100.

Kevin St. John, an attorney for Vos and LeMahieu, made a similar argument on behalf of his clients, who hold a 60-38 and 20-12 seat advantage in their respective chambers.

Supporters of fair maps turned out to testify against the rule change. They painted the request as a partisan power grab intended to keep Republicans in power.

“We supporters of the fair maps movement view this petition as a thinly veiled effort to derail the commission and its mission of nonpartisan maps,” said Christopher Ford, chairman of the People’s Maps Commission, a nonpartisan board Evers formed last year to draw fair maps that will contrast with the Legislature’s presumed hyperpartisan proposal.

Republicans controlled the Assembly, Senate, and governorship when the current maps were passed in 2011, giving themselves a tightly engineered, practically unbreakable majority in both legislative chambers. Look no further than the 2018 midterm elections, in which Democratic Assembly candidates received 53% of the vote but only came away with 36% of the Assembly seats.

The People’s Map Commission has no legal power, and legislative Republicans are almost certain to ignore its proposals, but the nonpartisan maps will give Democrats and fair maps organizers a powerful image to hold up against the Legislature’s assumed gerrymandering.

Hours after the Supreme Court hearing ended, the People’s Maps Commission met for a hearing on the 4th Congressional District, which encompasses Milwaukee and some of its suburbs. The district is the most diverse in the state and is currently represented in Congress by Rep. Gwen Moore (D-Milwaukee).

Much of the discussion centered on how the People’s Maps Commission can assure people of color can have adequate representation in the Assembly and Senate, and how gerrymandering has hurt underrepresented groups in the past.

Wisconsin is one of 24 states that require “communities of interest” to be taken into account during redistricting. Communities of interest are defined by the National Conference of State Legislatures as “geographical areas, such as neighborhoods of a city or regions of a station, where residents have common political interests that do not necessarily coincide with the boundaries of a political subdivision, such as a city or county.”

In highly segregated metropolitan areas such as Milwaukee, racial and ethnic groups are frequently in their separate neighborhoods, which each could be considered their own community of interest. But respecting communities of interest during redistricting is also pertinent in other areas of the state with high Native American or Latino populations.

“Representative democracy is not just a matter of making sure you have the same number of people in each district,” said Rebecca Lopez, a labor and immigration attorney who gave a presentation on Wisconsin’s Latino population.

Tehassi Hill, chairman of the Oneida Nation, said it has historically been a challenge getting adequate Native American political representation. Hill said reservations are often ignored as communities of interest. He also pointed out that many Native Americans live near—but not within—reservations, so their voting power is further diluted.

“I guess my main ask for this commission would be that our reservations not be divided, and potentially that Native American people leaving near reservations also be able to be included as a part of that district,” Hill said.

The redistricting fight will go into full swing later this year once the 2020 US Census data is released.

Politics

Biden makes 4 million more workers eligible for overtime pay

The Biden administration announced a new rule Tuesday to expand overtime pay for around 4 million lower-paid salaried employees nationwide. The...

Biden administration bans noncompete clauses for workers

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) voted on Tuesday to ban noncompete agreements—those pesky clauses that employers often force their workers to...

Local News

Readers Poll: Top Bowling Alleys in Wisconsin

Looking for the best bowling in Wisconsin? Look no further! Our readers have spoken in our recent poll, and we have the inside scoop on the top...

8 Wisconsin restaurants Top Chef judges are raving about

Top Chef’s 21st season is all about Wisconsin, and on-screen, it’s already apparent that the judges feel right at home here. But, while filming in...