#image_title

This community has been hit hard by the virus. It is also much less likely to trust medical research and the vaccines produced by research.

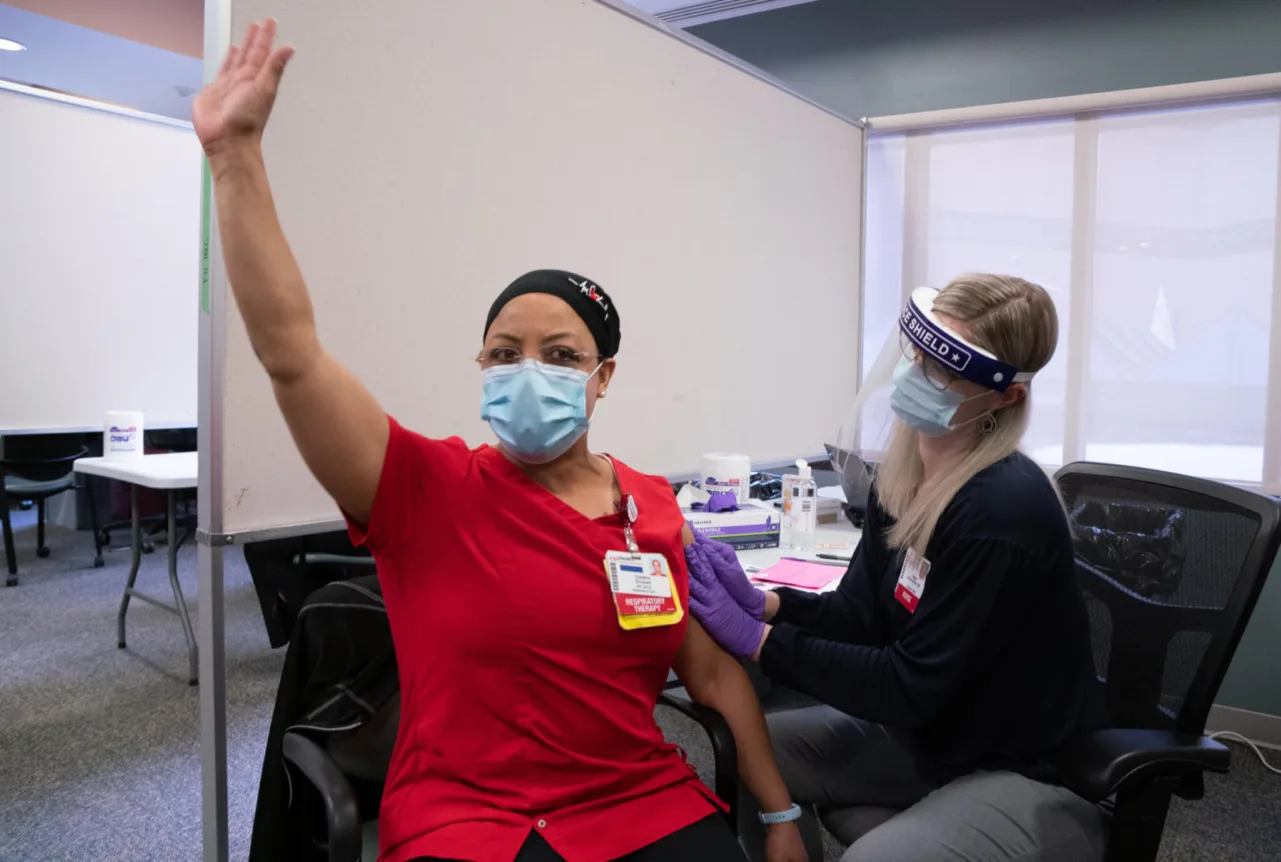

When UW Health registered respiratory therapist Chestina Schubert became the first person at University Hospital and in the state of Wisconsin to receive the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine Monday, she was taking the shot for her community as well.

“I want people to know and see for themselves that it is safe,’’ said Schubert, a Black woman. “Vaccines do work. For my community, now they have a name and a face of someone who got the vaccine.”

Schubert, who is certified for adult critical care, has spent the past nine months caring for COVID-19 patients, who now occupy seven to ten units at the 505-bed hospital.

“It’s exhausting, it’s sad, it’s heartbreaking,’’ she said, of the numbers of patients with severe COVID infections. “I want to inspire people, especially the patients that look like me that I take care of everyday.’’

As the vaccines begin arriving, public health officials have already begun working on the issue of vaccine equity, said Shiva Bidar-Sielaff, UW Health vice president for equity and inclusion.

Although communities of color have been hit hard by the virus, they’re also much less likely to trust medical research and the vaccines produced by research. This is due to a long history of studies like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which the US Public Health Service prevented Black men suffering the ravages of syphilis from being treated with penicillin.

That study occurred in Macon County, Alabama, from 1932 to 1972, making it a memorable incident for the older generation of Black men and women. In May of 1997, former President Bill Clinton issued a presidential apology for the study.

“Medical people are supposed to help when we need care, but even once a cure was discovered, they were denied help, and they were lied to by their government,” Clinton said during his apology speech. “Our government is supposed to protect the rights of its citizens; their rights were trampled upon.”

UW Health began working this past summer on the issue of vaccine trust, Bidar-Sielaff said, because it is a site for a trial of the AstraZeneca vaccine and health professionals wanted to recruit more people of color to test the vaccine.

“Because this trust gap exists, it’s important that they hear the message from people in their own community, in a way that is racially and linguistically concordant,’’ Bidar-Sielaff said.

To begin answering community questions about the COVID-19 vaccines, UW Health is doing community outreach with its faculty of color. Dr. Patricia Tellez-Giron, a family medicine physician, took questions about vaccines during her monthly show on the Spanish language radio station, La Movida.

And two Black women who are pediatricians, Dr. Sheryl Henderson and Dr. Jasmine Zapata, had a breakfast meeting with the Foundation for Black Women’s Wellness on the topic of vaccines.

It’s no coincidence that Schubert, a frontline healthcare provider, received the first dose of vaccine. With vaccine supplies limited, Bidar-Sielaff, said a UW Health equity group created a prioritization algorithm for which employees will be vaccinated first.

Frontline workers in COVID units, such as Schubert, have priority. But the formula also takes into consideration age and the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) to prioritize people from communities of color, because they have suffered a disproportionate impact of COVID-19.

“We certainly did want to make sure that staff of color from the COVID units have access to the vaccine,’’ Bidar-Sielaff said. The priority also extends to non-medical and nursing staff, such as the cleaning and culinary staffs who support the COVID units.

Schubert said she was happy to publicize her vaccination because having a personal connection to someone involved with the vaccine can help overcome the historic mistrust.

Knowing a Black woman, Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, a viral immunologist with the National Institutes of Health, was involved in developing the vaccine “gives me added trust” in the vaccine, Schubert said.

Now she’s talking to her patients about getting the vaccine and is happy to talk to church and community groups via Zoom or other online platforms to answer any questions they would like to put to her. She says the most common question she gets is, “How are you feeling?”

“I’m doing well,’’ she said, two days after her historic vaccination. “The only thing I had was some pain at the injection site. I feel great. I want to do more to inspire my community to get vaccinated.”

New Biden rules deliver automatic cash refunds for canceled flights, ban surprise fees

In the aftermath of a canceled or delayed flight, there’s nothing less appealing than spending hours on the phone waiting to speak with an airline...

One year on the Wienermobile: The life of a Wisconsin hotdogger

20,000+ miles. 16 states. 40+ cities. 12 months. Hotdogger Samantha Benish has been hard at work since graduating from the University of...

Biden makes 4 million more workers eligible for overtime pay

The Biden administration announced a new rule Tuesday to expand overtime pay for around 4 million lower-paid salaried employees nationwide. The...

‘Radical’ Republican proposals threaten bipartisan farm bill, USDA Secretary says

In an appearance before the North American Agricultural Journalists last week, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Secretary Tom Vilsack...