#image_title

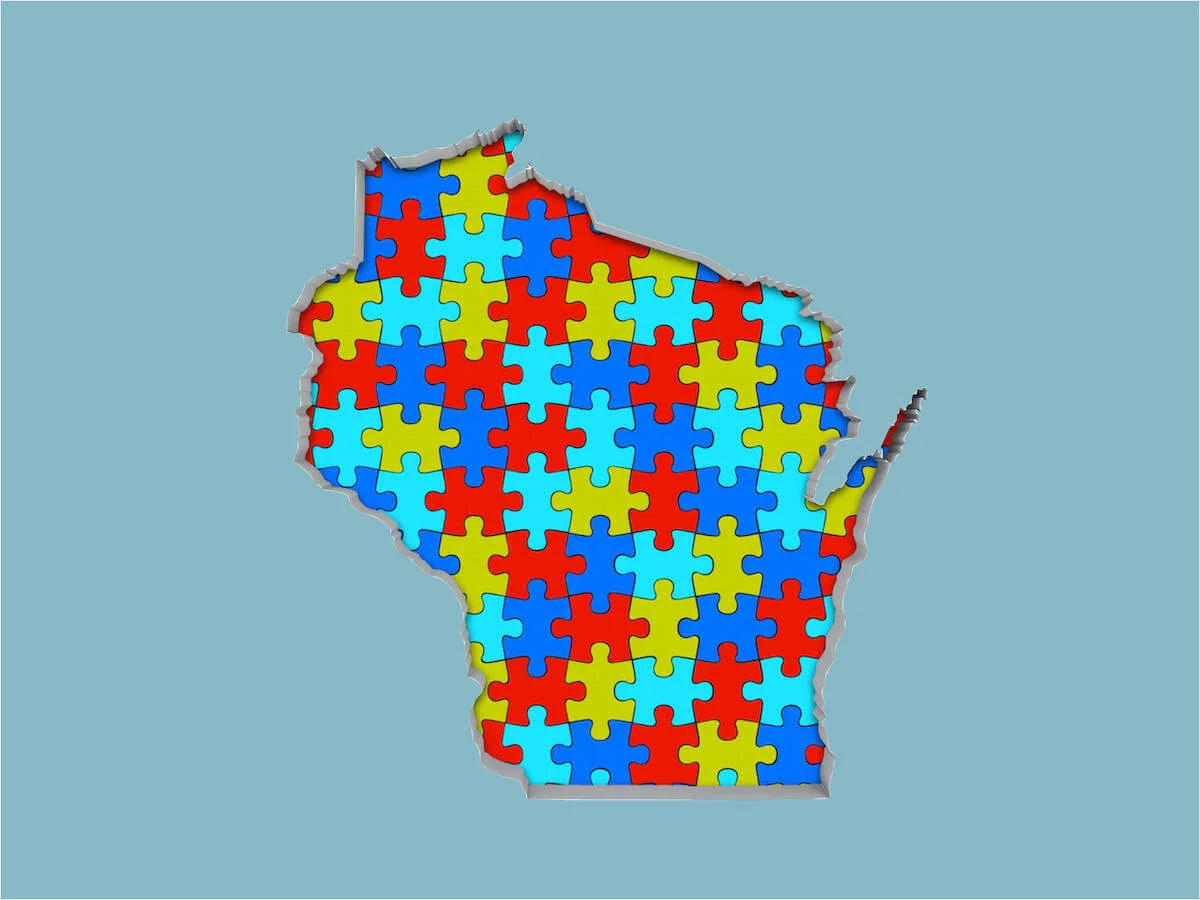

Rigged maps from 2011 lead to an Assembly and Senate out of whack with the people’s preferences nearly a decade later.

With all 99 of Wisconsin’s Assembly members and 16 of the state’s 33 Senators up for election on Nov. 3 in a state that had a slight Democratic advantage two years ago, voters typically could be expected to see a fair amount of turnover when vote totals for legislative seats are announced.

It’s possible, election analysts say, but not likely because those districts are among the most gerrymandered in the country.

After Republicans took over both houses of the Legislature in the 2010 elections, GOP lawmakers redrew their district lines—to benefit themselves and future Republican candidates, allowing their party to retain control of the Legislature by a relatively wide margin, even in years like 2018 when the Democratic vote statewide was more than that for Republicans.

In that election, incumbent Republican Gov. Scott Walker lost his re-election bid by 1% to Democrat Tony Evers. Yet Walker outpolled Evers in 63 of Wisconsin’s 99 Assembly districts, and 64 Assembly seats are currently held by Republicans.

In addition, Lieutenant Gov. Mandela Barnes, Attorney General Josh Kaul, and Treasurer Sarah Godlewski, all Democrats, were elected to state office in that election. Like Evers, their positions are determined by a statewide vote and not by districts drawn by politicians.

Those seemingly conflicting election results—Republicans maintaining a stranglehold on the state Legislature while Democrats win the popular vote—are evidence of the prevalence of gerrymandering in Wisconsin, political analysts said.

“Generally speaking, gerrymandering does exactly what it’s supposed to do,” said Geoff Peterson, chairman of the UW-Eau Claire political science department. “It divides up the votes and makes sure a certain political party wins a majority of the seats.”

Gerrymandering has been used throughout US history to establish district boundaries that made it more likely members of one party would be re-elected by grouping more people likely to vote for those candidates, often at odds with traditional or geographical divisions. The process of designing districts became especially insidious following the 2010 census, when new mapping technology was applied to statewide voters lists, making it easier for the party in power to stay in power.

Republicans in 2011 redrew the election maps without Democrats being able to oppose those changes. Republicans leaders and private advisors drew their maps behind closed doors and required their lawmakers to sign nondisclosure agreements in order to see maps of their districts before the public.

Since then the state’s political districts have been stacked toward Republicans, with some districts designed to benefit Democrats so that Republicans can be more easily elected in most of the others.

Republicans have defended the current election maps, saying Democrats have sought to gerrymander in the past. Attempts to change the maps–mostly notably a US Supreme Court decision on the matter–have been unsuccessful.

RELATED: Plaintiff in Landmark Wisconsin Gerrymandering Case Says ‘Vote to Create a Fair Map System’

Gerrymandering, especially when it’s done as thoroughly as happened in Wisconsin, is difficult to overcome, Peterson said. But it is possible, he said, when a candidate at the top of the election ticket wins by a significant margin and benefits candidates of the same party further down the ticket.

Modern gerrymandering is heavily data-based, Peterson said, with many districts drawn to roughly the same Republican-Democrat margins. That means if there is a statewide wave in favor of one party, it could have an outsized impact on election results, he said. Instead of a couple of districts being flipped, perhaps dozens could be.

“Is that likely? Who knows,” Peterson said, noting that depends in part on voter turnout. “Given what we are already seeing with high numbers with mail-in voting, that could be the case this year.”

Many Wisconsin residents are opposed to gerrymandering, saying it disempowers many people’s votes. The concept of a nonpartisan redistricting commission has widespread support among Wisconsin voters, according to a Marquette University Law School poll.

Gerrymandered districts make it more likely that incumbent candidates will be re-elected, Peterson said. In addition, some analysts said candidates with more extreme political stances tend to be elected in strongly gerrymandered districts, making it more difficult for the two political parties to find common ground when governing.

That has been evidenced in the state Legislature in recent years, when Republicans and Democrats have found little common ground. The political stalemate seems likely to continue regarding the redrawing of the next election map next year, after the 2020 census is finished.

Gov. Tony Evers last year announced the formation of the People’s Maps Commission, charged with redrawing the state’s election maps. Evers proposed such a commission as part of the 2019-21 state budget, but Republicans removed it, prompting the governor to subsequently establish it by executive order.

Assembly Speaker Ron Vos (R-Rochester) said the governor’s map effort is politically charged, and Republicans will draw their own map. If lawmakers follow the usual map-drawing process, Evers could veto their result.

If an anticipated stalemate regarding election maps takes place, the issue likely would head to court. Lawsuits could begin once census data is ready, scheduled for April 2021.

Opinion: Many to thank in fair maps victory for Wisconsinites

On February 19, 2024, Governor Tony Evers signed into law new and fair state legislative maps, bringing hope for an end to over a decade of...

Opinion: Empowering educators: A call for negotiation rights in Wisconsin

This week marks “Public Schools Week,” highlighting the dedication of teachers, paras, custodians, secretaries and others who collaborate with...

Op-ed: Trump’s journey from hosting The Apprentice to being the biggest loser

Leading up to the 2016 election, Donald Trump crafted an image of himself as a successful businessman and a winner. But in reality, Trump has a long...

Not just abortion: IVF ruling next phase in the right’s war on reproductive freedom

Nearly two years after the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, another court is using that ruling to go after one of the anti-abortion right’s...