#image_title

Eau Claire becomes 4th Wisconsin city to condemn Trump plan after hearing stories of fleeing war, building new lives

As a young boy John Lor remembers his father leading a group of Hmong soldiers, men and boys recruited by the CIA to fight the so-called “secret war” against Communist North Vietnamese forces who waged a life-and-death struggle in southeast Asia.

He remembers the fall of Saigon at the end of April 1975, the withdrawal of United States troops the Hmong had sided with, and how he and his family fled into the jungle, then the mountain country, to escape imprisonment and almost certain death from North Vietnamese soldiers seeking to punish and eradicate those who had helped Americans during the Vietnam War.

He remembers fearing death at any moment, how his family moved frequently from place to place, hoping to stay one step ahead of the foes searching for them. He remembers struggles to find enough food to stay alive, huddling with family members to escape the elements.

He remembers one day in October 1987, when Lor — the oldest of nine siblings — his wife, Yer, and a brother left the rest of their family, and, after a harrowing month-long journey, how they made the dangerous crossing of the Mekong River to a refugee camp in Thailand.

He remembers the day, May 25, 1989 when he arrived in Eau Claire, when he felt overwhelmed by a sense of both relief at having escaped his homeland and fear about what awaited him in his new home.

And Lor, now 52, remembers the mix of anger and fear he felt when he learned last month that President Donald Trump’s administration was negotiating with government officials in Laos seeking an agreement that would allow the U.S. government to deport an estimated 4,500 Hmong and Lao refugees.

The proposal is directed at refugees who have been unable to become citizens because of criminal records, even if they have served time for their infractions and have led crime-free lives for years afterward.

“This makes me really frustrated and angry,” said Lor, an Eau Claire City Council member, on Monday several hours before speaking at a rally at the Unitarian Universalist Congregation Church in Eau Claire.

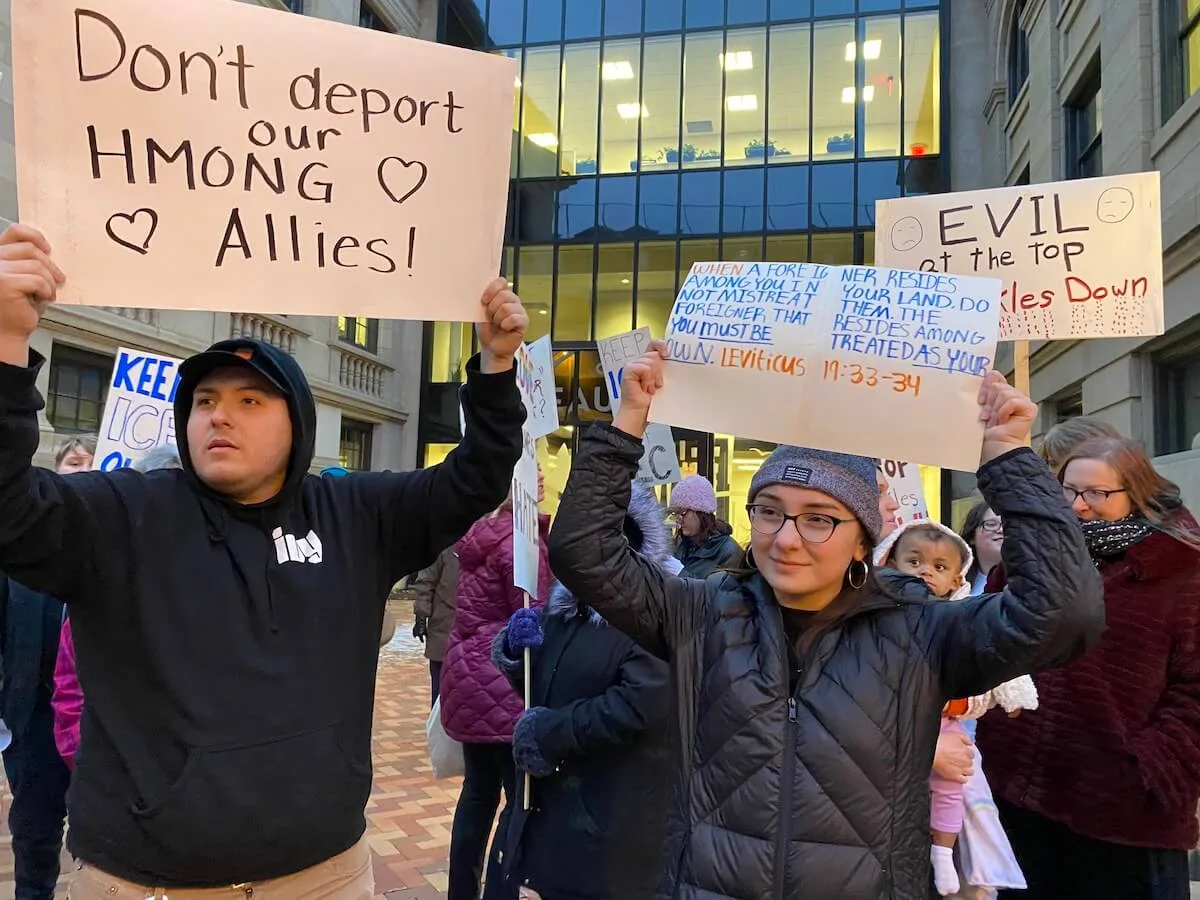

The rally was attended by more than 100 people opposing the deportation measure. About an hour later Lor spoke during a City Council meeting on behalf of an ordinance he authored condemning the deportations.

“We came to this country as refugees who had helped the CIA, who had fought on the side of the United States,” Lor said. “For the president to single out this minority group … I don’t think he knows how much the Hmong helped in that war and how many of us died to help this country. We gave up everything and lost so much.”

On Tuesday the council in Eau Claire unanimously approved the ordinance, joining Madison, Appleton and Wausau in condemning the deportation effort. Those actions have no regulatory power but are instead intended to convince federal legislators to disallow Hmong deportations.

Taking such action is necessary to show public support of the Hmong people and convince Congress to allow the roughly 300 in Wisconsin facing deportation to be allowed to remain here, said Yee Leng Xiong, director of the Hmong American Center in Wausau.

“We have to do what we can to show there is support for Hmong people in this country,” Xiong said. “We need to make our voices heard.”

Hmong and Lao people facing deportation already have served time for their crimes, Hmong leaders and other advocates said. Many who could be sent to Laos were at-risk teens and became involved in gangs or other illicit behavior as a means of protection, Xiong said.

“These are people who have paid their debt to society,” Xiong said, “and many are now productive members of our society.”

‘Living in fear’

Most of the Hmong facing possible deportation have lived in this country for a decade or longer, advocates said. Sending them to a country where most have no history, little to no family and to a place where they don’t speak the language or know the customs isn’t responsible, said U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wisconsin.

Forcing Hmong residents to Laos is not only poor policy but could prove life-threatening, she said, noting the Lao government has a history of repression of Hmong citizens that could endanger those sent there.

“There is a long and dark history of human rights violations by the Communist government of Laos against the Hmong, and I am deeply concerned that the Trump administration would tear families apart in Wisconsin and target Hmong and Lao refugees residing in our state,” Baldwin said during a recent interview.

The issue of Hmong and Lao immigrants being deported garnered headlines after U.S. Rep. Betty McCollum, D-Minnesota, wrote a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo opposing the plan, saying it would be “unconscionable to deport individuals to any country in which the U.S. knowingly puts them at risk.”

Such actions are heartening to Lor and others. The support shown by people who marched from the church to City Hall and filled the City Council chamber and another room, and the 19 speakers who addressed council members in support of Hmong citizens, are needed to help dissuade the federal government from harming Hmong families, Lor said.

Many Hmong across Wisconsin and the U.S. “are living in fear” of deportations, he said. That was evident by the reactions of Hmong speakers who addressed the City Council. Several broke down in tears as they described the difficulties Hmong people have faced already and their concerns about further harm to families if deportations occur.

True Vue grew up in Eau Claire after her birth in a Hmong refugee camp in Thailand. She described how challenges her family faced after the Vietnam War continue to adversely impact them and many in the Hmong community.

“I was lucky. I had many positive influences here in Eau Claire,” said Vue, who went on to graduate from UW-Eau Claire. “But not everyone had a positive life like mine.”

Without a place to fit in, some of her friends turned to gangs and committed crimes, Vue said. Many of those people are now responsible adults, she said, and are good parents who earn money for their families.

“Now, if these people are deported, we are going to split up those families,” she said. “We can’t do that to them.”

Lor knows firsthand about lost time with family. Three years after his escape from the jungle to Thailand, his parents and remaining siblings did the same. But his parents and five siblings were sent back to Laos as they no longer qualified for refugee status. They and Lor’s mother made it to Eau Claire a dozen years later, in 2002, after Lor’s father died.

“Our families were already split up and torn apart after the war in Vietnam,” Lor said. “Now we’re talking about tearing apart these families again. It’s just not right.”

Wisconsin court commissioner resigns after dispute over immigration warrant

A Wisconsin court commissioner has resigned from his job after he asked to see an immigration arrest warrant, the latest conflict between judges and...

WI Farm Bureau: Immigration reform could address labor shortage

By Judith Ruiz-Branch The state’s largest farm organization wants what it calls "meaningful" immigration reform rather than aggressive...

Trump administration hands over Medicaid recipients’ personal data, including addresses, to ICE

WASHINGTON (AP) — Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials will be given access to the personal data of the nation’s 79 million Medicaid...

Would You Pass the US Citizenship Test?

As born & bred Wisconsinites, we should be able to answer even the hardest questions... right? Let's find out. More than 50,000 immigrants...