#image_title

No move to cap may lead to environmental dangers

A Chippewa County sand mine that has been inoperable since last year serves as a warning in Wisconsin that reclamation of such sites may not be fully funded, according to a prominent state environmental organization.

Tony Wilkin Gibart, executive director of Madison-based Midwest Environmental Advocates, said the failure of the operator of Superior Silica Sands to provide enough money for the reclamation of that mine, near the Chippewa County village of New Auburn, and how the issue is resolved could have statewide ramifications as other sand mines experience continued economic struggles.

Chippewa County officials suspended the mining permit for Superior Silica Sands last July after failed attempts to secure an additional $1.7 million in reclamation funding from the company. The county has about $3 million from the company to pay for reclamation of the mine, less than the $4.7 million projected cost.

Just 10 days later Emerge Energy Services, which owns the Superior Silica Sands mine and seven other sand mines and processing facilities in Wisconsin, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in federal court, further evidence of the company’s fiscal troubles. Chippewa County subsequently filed a lawsuit in federal court against the company for its failure to fully finance reclamation work and its incomplete water monitoring at the site.

“The bankruptcy of Superior Silica Sands, which owns eight facilities in Wisconsin, is not occurring in a vacuum, and we should expect these types of issues to emerge more frequently,” Wilkin Gibart said.

Sand mining companies in Wisconsin typically are required to post at least a portion of reclamation funding — money to pay to restore mine sites to their pre-mining condition as much as possible — prior to mining, and those dollars are used by local governments to pay for reclaiming mine sites.

However, as the Superior Silica Sands mine and others across the state continue to struggle financially, whether they will have funding to pay to recover sites as required is a growing concern, Wilkin Gibart said. Because reclamation in Wisconsin depends on permitting decisions at the county level, there are significant variations as to what degree local communities and governments will be able to hold frac sand companies responsible for cleanup, he said.

Requirements that mining companies borrow money up front to pay for reclamation or other environmental harms were intended to ensure sites were reclaimed properly, Wilkin Gibart said. But those agreements varied from county to county, he said, and in some cases may not be sufficient.

“Counties didn’t necessarily have the expertise or knowledge to set these standards,” he said.

Pat Popple, a Chippewa Falls resident who has been speaking for the past decade about concerns related to sand mines, said she worries not only about environmental impacts of mines but about the potential lack of money for reclaiming those sites.

“Now we’ve seen how Superior Silica Sands doesn’t have the money to pay for reclamation, and you have to think that will be an issue for other mine operators too,” she said.

Roberta Walls, nonmetallic mining coordinator with the state Department of Natural Resources, said Superior Silica Sands is one of just two industrial sand mine sites in Wisconsin that have declared bankruptcy. Other non-industrial mines have gone bankrupt previously, she said, and the outcomes in those cases will help inform officials about the process involving the Superior mine.

Chippewa County Land Conservation and Forest Management Director Dan Masterpole declined comment on specific questions related to the Superior Silica Sands site, saying the ongoing lawsuit prevents him from doing so. However, he said county officials are working with the DNR to plan an upcoming public meeting to discuss issues related to that mine.

Wilkin Gibart, Popple and others also expressed environmental concerns, from groundwater issues to particulates in the air, related to sand mines. DNR records show tests revealed levels of arsenic and other heavy metals at the Superior Silica Sands mine at significantly higher levels than state guidelines, and Walls said heavy metals have been detected at other mine sites. Arsenic is a naturally occurring metal in the ground that is listed as a carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency if present in high amounts.

Popple said she worries about excess arsenic and other heavy metals at the Superior mine and is afraid about possible groundwater contamination there too. “You look at the impact of these mines, and it’s like we’re dealing with a ticking time bomb,” she said.

Wisconsin’s sand mines are located in the state’s western region where sand that is especially durable and has a spherical shape is desired for hydraulic fracturing, a process in which sand is mixed with water and chemicals and then pumped underground under high pressure to extract gas and oil. Demand for that sand prompted a sand mining and processing boom in western Wisconsin for most of the past decade.

However, the market for Wisconsin sand softened significantly after a big drop in oil prices and the discovery of sand in Texas that, while not as high-quality as that found in the Badger State, also works in the hydraulic fracturing process. Much of the frac sand mined in Wisconsin was transported to oil fields in Texas and Oklahoma, but with available sand much closer, owners of those operations no longer are willing to pay to import sand from Wisconsin.

According to DNR figures, the state was home to 128 industrial sand mines in 2016, including many seeking permits. That figure is about 90 currently, Walls said, and of those, the majority are idle.

Analysts said the state’s sand market is expected to remain depressed in 2020 and perhaps beyond. Those conditions mean more sand mine owners could declare bankruptcy, following in the footsteps of Superior Silica Sands, Wilkin Gibart said.

“(Mine site reclamation) is a major concern as frac sand companies pull out of Wisconsin,” he said.

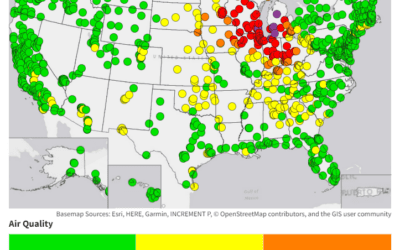

Popple shares that concern. The 80-year-old former educator began publicly advocated against the adverse impacts of sand mines in 2008. Three years later she began publishing the Frac Sand Sentinel, an online newsletter she said has several thousand readers. Several years ago she began working with UW-Eau Claire environmental public health program associate professor Crispin Pierce on a project that monitors air quality near sand mines.

A decade after attending her first meeting about those mines, Popple remains committed to working on that topic.

“I have such a hard time seeing what is happening to our climate today,” she said. “Environmental harm is happening with sand mines right here in my community and elsewhere across this state, and I want to keep fighting it.”

From the top: What is this Inflation Reduction Act that’s so important to the presidential election?

It’s part of President Biden’s legislative agenda—the most productive in generations, yet few Americans know all the details of how it improves...

Here’s how to lower your home’s energy bill under the Inflation Reduction Act

It begins with assessing your home’s current energy use, planning improvements, then getting connected to the credits and rebates that can create...

Biden’s EPA announces rules to slash coal pollution, speed up clean energy projects

The Biden administration last month announced a set of four final rules designed to reduce harmful pollution from power plants fired by fossil...

How to apply for a job in the American Climate Corps

The Biden administration announced its plans to expand its New Deal-style American Climate Corps (ACC) green jobs training program last week. ...