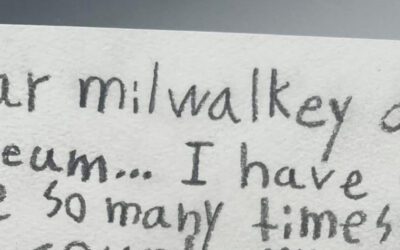

An ofrenda honoring Miranda Alvarez’s deceased loved ones displayed in her home on Oct. 14, 2025, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. (USA Today via Reuters Connect)

It was completely dark outside, and in the house, the night Cinthia Borunda-Valadez put an image of her father-in-law on her ofrenda, nearly a year after his death. The next time she looked at his picture, it was surrounded by a bright light resembling gentle flames.

Borunda-Valadez, 39, and her husband searched for every possible light source, but could not find where the light emanated from, she said.

“There was no light, no sun, no sun glare,” Borunda-Valadez said. “It was crazy, eerie.”

This was the first Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, Borunda-Valadez celebrated with her family since her father-in-law passed, and the first time she felt his presence in her home in months.

Day of the Dead takes place on Nov. 1 and 2 and celebrates the lives of loved ones who have died by sharing their stories with others to keep their memory alive, according to Sergio González, associate professor of history at Marquette University.

The Mexican holiday is said to mark the short period where the spirits of those who have died can cross over for a brief reunion with the living.

In the weeks leading up to the holiday, families set up ofrendas, or altars, dedicated to loved ones who have passed away. The altars usually contain photos and physical objects dedicated to the deceased or items that previously brought comfort to them, González said.

It’s typical to see offerings of food, the late-person’s favorite items and other traditional symbols tied to the holiday and Mexican culture, González said.

Many altars include traditional items like marigold flowers, which are used to create trails from a person’s grave to their family home to guide the spirit back to their loved ones.

“What makes ofrendas particular and wonderful is that they are unique,” González said. “It offers a space for representation and for memory making. No ofrenda is the same as any other because each speaks to the memories that one has with those who have passed.”

Families across Milwaukee’s south side celebrate Day of the Dead in many ways. Here are just a few:

Honoring her family tree through new traditions

Borunda-Valadez said she never celebrated Day of the Dead when she was a child; neither did any of her family members.

But for the last ten years, on the Day of the Dead, Borunda-Valadez’s family members gather in her living room around her ofrenda, which takes up nearly an entire wall in her Bay View home.

The ofrenda features photos of family members and pets who have passed away over the years. The photos are joined by the favorite foods and the belongings of those who have passed on, and decorations collected from travels to Mexico, Borunda-Valadez said.

“This is basically our family tree,” Borunda-Valadez said.

After suffering two miscarriages, Borunda-Valadez created a painting of two angels, which she adds to her ofrenda each year to remember the children she lost. Using her art to honor and remember them has helped her heal and move forward, she said.

“The ofrenda is not just for family or one person, it’s for everybody you have lost,” Borunda-Valadez said. “It’s very important, to in one way or another, honor them.”

Surrounded by photos of their loved ones, and the items they cherished most in life, Borunda-Valadez and her family members spend the holiday lighting the altar’s candles and burning incense. They sit together eating pozole soup, Pan de Muerto and hot chocolate while sharing stories of family members who have passed on.

Borunda-Valadez was born in Mexico and immigrated with her parents when she was two months old. In Mexico, her family’s church did not celebrate Day of the Dead, so the tradition never took hold among her relatives.

Growing up on Milwaukee’s south side, Borunda-Valadez said she started volunteering at Day of the Dead events as an artist and performing at events with the Aztec dance group, Ballet Folklorico Mexico de los Hermanos Avila, she said.

The more she participated in holiday events across the city, the more she longed to start the tradition of putting up an ofrenda for the holiday, Borunda-Valadez said.

Borunda-Valadez began building her own ofrendas after the death of her grandmother in 2015 to help cope with the loss, she said.

“I told my husband, I need to do this, and we started adding our family members,” she said. “We realized we have a lot of family members that have passed, and each year, unfortunately, we keep adding.”

Each year, the ofrenda reminds Borunda-Valadez to share the stories of those close to her with her children, she said. The holiday has also helped her introduce and explain the idea of death to her two daughters in a way that reframes it into a celebration of life.

Borunda-Valadez said she hopes her daughters will continue the tradition of setting up altars when they start their own families and continue to pass down the stories of their relatives for generations.

Remembering loved ones across generations

Micaela Ortega, 76, is the last member of her family from her generation left, and each year she spends hours putting together her ofrenda to help share the stories of those who have passed.

She loved putting together her ofrenda with her great granddaughter, who is often captivated by the items set out for each deceased relative, Ortega said. She hopes one day, the youngest in her family will be inspired to set up their own — passing down the stories of those she loves.

Ortega, who immigrated from Mexico to Wisconsin when she was 10, began putting up her ofrenda around five years ago with her daughter, Leticia Solano. She dedicated her ofrenda to several family members who have passed away over the years, including her own mother and grandmother.

Multiple generations of her family are displayed proudly next to food offerings, paper marigold flowers and sugar skull figurines. Each year, her home is the gathering place for the holiday, and she feels grateful to be able to share her ofrenda and the stories it carries with her family members, Ortega said.

Ortega’s granddaughter, Miranda Alvarez, 33, started putting up her own ofrenda around five years ago as well. She said she was first inspired by her grandmother.

Alvarez’s ofrenda honors her late father, her father-in-law, her godmother and her two nephews who died in their teens. She said she starts putting up her ofrenda at the start of Hispanic Heritage Month on Sept. 15 and keeps the altar up until after the holiday.

“I feel like the longer my ofrenda is up, it’s just a good way to pass by and honor them,” Alvarez said.

Along with photos for each of the family members inside the painted frames on her altar, Alvarez includes items that represent what they valued in life or the memories they shared.

Her father, Jose de Jesus Jimenez Gutierrez, and her father-in-law, Felipe Alvarez, are featured proudly at the top of her ofrenda. Alvarez said she included two small liquor bottles and a small sombrero in the middle of their photos so they can enjoy their favorite drinks on the holiday.

To honor her godmother, Celina Gonzalez, who collected Barbies throughout her life, Alvarez said she includes a collection of Dia de los Muertos-themed Barbie and Ken dolls. Each doll has its face painted like La Catrina, a figure that symbolizes life as a part of death in Mexican culture.

“I remember her babysitting me when I was younger and just admiring her Barbie collection,” Alvarez said.

Alvarez’s close friend Michael Williams loved watching sports in his life. To honor him, Miranda sets out a sugar skull bobblehead dressed like a baseball player that she collected at a Brewers’ fundraising event.

The youngest family members on Alvarez’s ofrenda are Sebastian Florentino, her 14-year-old nephew who died of gunshot wounds in 2023, and his 16-year-old brother, Giovanni Florentino, who passed a year before in a car accident, she said.

Several photos of the two of them are displayed proudly on her altar, and the night before the holiday, Alvarez always sets out their favorite snacks, she said.

“It’s helped me cope with the loss and finding comfort in celebrating their lives, keeping their memories alive,” said Alvarez.

Sharing these memories with her three daughters motivates Alvarez to continue putting up her ofrenda each year, to connect with their roots and family history, she said.

“It’s important to me to have my children know who their family is,” Alvarez said. “It’s important for them to know who’s important in my life and kind of made me into the person I am today.”

Introducing traditions and connecting with cultural roots

During October, weeks before Day of the Dead, Bianca Velasco, 31, and the teachers at her daycare center, Like Home Learning Center, gather photos from families and craft materials to make ofrendas in their classrooms.

Most of Velasco’s students are Mexican immigrants or Mexican Americans. The center’s lessons are taught in English and Spanish..

Since Velasco opened the learning center in November 2023, she’s made a point to celebrate the holiday with her students each fall.

Velasco said teaching about the holiday encourages her Mexican students to connect with their culture and invites students who are not Mexican to learn about new traditions different from their own, she said.

“I feel like sometimes Dia de los Muertos is put on the side, especially here, with some families. They leave their country, and they don’t really know how to bring that up to their kids,” Velasco said. “We believe that building those ofrendas for them is bringing that culture and their roots back.”

The holiday’s traditions are close to Velasco and her family as she sets up an ofrenda in her Milwaukee home with her two daughters each year. Several of her family members in León, Guanajuato, Mexico, also put up their own ofrendas for the holiday, she said.

“It brings a new life to the kids, and it lets them see the world differently,” Velasco said.

Velasco and her teachers ask parents to send in photos of their loved ones who have passed on to include on the ofrendas students build in their classrooms, she said.

Students spend several weeks making Papel Picado, drawings and food offerings made of playdough to leave out on the ofrenda for their loved ones, Velasco said.

“Remembering their family members through colors, flowers, through putting food on the ofrenda — it’s teaching them that they can remember their loved ones with love,” Velasco said.

“It doesn’t have to be sad. It’s all about celebration, the celebration of life.”

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: How Milwaukee families keep memories alive through Día de los Muertos ofrendas

Reporting by Alyssa N. Salcedo, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

USA TODAY Network via Reuters Connect

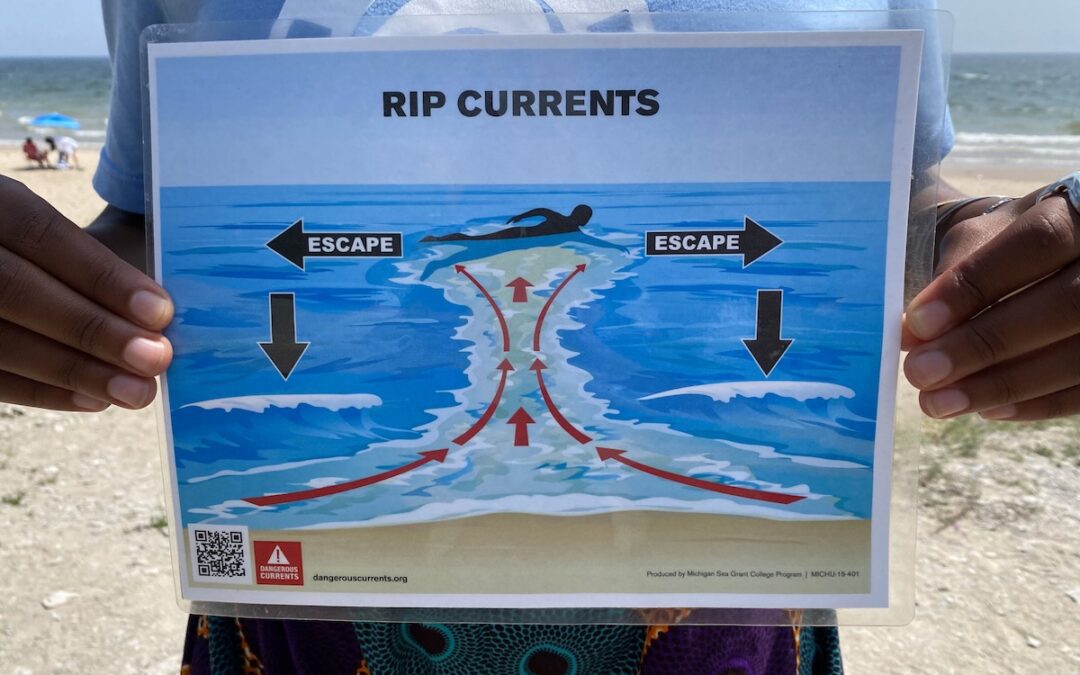

‘A shared responsibility’: Milwaukee Beach Ambassadors work to make Lake Michigan safer

If you frequent Milwaukee's McKinley or Bradford beaches, you likely have seen — or even spoken to — a Beach Ambassador. Dressed in baby blue...

Jim Lovell, Milwaukee’s hometown astronaut and hero, dies at 97

Commander of Apollo 13 and astronaut aboard Apollo 8, Lovell uttered the famous line, “Houston, we have a problem.” Milwaukee’s own Jim Lovell,...

9 WI businesses staffed by people living with disabilities

Learn about how you can support these Wisconsin businesses staffed by people living with disabilities. Running a successful business isn’t just...

No ‘Front Row’? Bob Uecker’s Famous Beer Commercials Almost Didn’t Happen

Bob Uecker’s now-iconic “I Must Be in the Front Row” Miller Lite commercial almost never happened! Here’s the story ⤵️ It was 1984. Miller wanted...