Dozens of protesters gather in the Wisconsin state Capitol rotunda in Madison on June 22, 2022 as Republican lawmakers prepare to reject Gov. Tony Evers' call to repeal the state's 1849 ban on abortions. (AP Photo/Todd Richmond)

Wisconsin is getting national attention as the state’s pre-Civil War abortion ban forces women with life-threatening conditions to wait for doctors who have to wait for lawyers.

The tragic story of a 10-year-old Ohio girl—raped, impregnated, forced to travel to another state for abortion care, and lied about by Republicans trying to marginalize her case—has helped Americans realize something shocking in the wake of the US Supreme Court’s repeal of Roe v. Wade: Her story is not nearly as rare.

Stories about girls and women facing life-altering and life-threatening situations during pregnancy—whether planned or unplanned—have moved from quiet corners to the most public stages in American dialogue, as a nation comes to grips with the once-unthinkable consequence of conservative justices ripping away what had been a Constitutional right for nearly a half-century.

The results so far show a growing level of uncertainty, fear, and frustration for everyone involved: patients, physicians, lawyers, family, and more. The only people feeling sure of themselves are politicians who see binary choices and none of the shades of gray that can lead to complications, heartache, and death.

In Wisconsin, for example, a Washington Post story focuses on the delays in care as physicians try to understand the limits of a ban that was written by lawmakers in 1849, in a time of frontier medicine decades before women had the right to vote. The ban has no exceptions for pregnancies resulting from rape or incest—and its exception to save the life of the mother is worded in a way that could be interpreted as requiring two other physicians to sign off on the need to save the woman’s life.

Dr. Carley Zeal, an obstetrician/gynecologist (ob/gyn) shared how she hadto wait more than a week to give abortion medication to a patient at a risk of infection after a miscarriage. It wasn’t clear if the 1849 ban allowed for the removal of fetal tissue from the uterus of the woman whose bleeding was at risk of becoming severe—but perhaps didn’t necessarily rise to being life-threatening at first.

Also interviewed by the New York Times, Zeal said, “Even in these straightforward cases of basic ob/gyn practice, the laws leave providers questioning and afraid. These laws are already hurting my patients.”

Who decides when it’s safe—legally—for a doctor to ensure that a patient stays safe—literally? One of Zeal’s colleagues, Elana Wistrom, recently had to force a patient to wait more than an hour for treatment of a rupture so that a second and third physician could confirm her diagnosis.

“It turned my attention away from the bedside of the critical-care patient toward documentation,” Wistrom told the Post.

Dr. Kristin Lyerly, a Green Bay-based ob/gyn who has been an abortion provider, said waiting on second or third opinions is not a luxury afforded to women in distress in Wisconsin’s small, isolated communities.

“How do you find three physicians to come together and make a decision about this life-threatening condition during a time when, if it’s truly life-threatening, the patient could die in the process?” Lyerly told Canada’s CBC Radio. “I took an oath to take care of my patients, to listen to them, and to help them determine what the best course of action is within the context of their lives. And sometimes we just don’t have a lot of time to bring in other people just because politicians require it. Abortion is health care. Abortion is not political.”

Lyerly has been interviewed by several national media outlets and written a column in the Financial Times to make the point that pregnancy and abortion care cannot be covered in a single court decision that oversimplifies the risks to women and results in substandard care.

“The only way we can take care of these women, these families, these communities in a thoughtful, necessary way is to individualize their care. And that is exactly the opposite of what will happen with repeal,” she told UpNorthNews.

NBC Nightly News recently featured Heather Martell, a Chippewa Falls woman who faced the agonizing decision of terminating a pregnancy last year when she learned the child would be born with severe spinal, head, and heart abnormalities.

“I couldn’t allow him to come into this world to live hours or weeks in excruciating pain,” Martell said. “What I was doing saved my son.”

Adding insult to injury, she said, were the protesters at a facility in Minnesota who wrongly told her that there were better alternatives to the choice she and her husband made.

But that false sense of confidence has only grown in those who oppose freedom of choice for women in perilous situations.

“I’m fully supportive of what the Supreme Court did,” Republican Sen. Ron Johnson told a right-wing radio host. “I obviously confirmed the justices that handed down that correct decision.”

Johnson has previously said women wouldn’t have a problem traveling to another state if politicians in their home state ban abortion care. “It might be a little messy for some people,” he acknowledged.

Several regional and national newsrooms, including ABC News, have covered how clinics in Illinois have prepared for a large increase in the number of Wisconsin clients.

“Devastating,” is how Tanya Atkinson, president of Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, described the consequences for patients in the state where four clinics that provided abortion services had to cease operations and force women to travel hundreds of miles or potentially not receive any care.

“This all is a very new and very frightening territory for patients,” Atkinson said.

It’s similarly uneasy territory for providers, who now have to worry that their every move could be subject to legal scrutiny from extreme anti-abortion radicals.

Gov. Tony Evers has said he would grant clemency to any doctor prosecuted under the 1849 law. While it could provide relief for doctors thrust into life-or-death decisions, legal experts say the offer is overshadowed by fear of the initial prosecution that would require a request for clemency.

“The chilling effect of these laws is probably going to overshadow any kind of pledge by a governor that says ‘Look I’ll help you out if this comes to pass,’” said Rachel Barkow, a New York University School of Law professor.Additionally, that potential for clemency disappears whenever pro-choice governors are unseated. Evers is up for reelection this November. If he loses and a Republican takes charge, it’s all but certain that things will get even worse for women and providers in Wisconsin

Politics

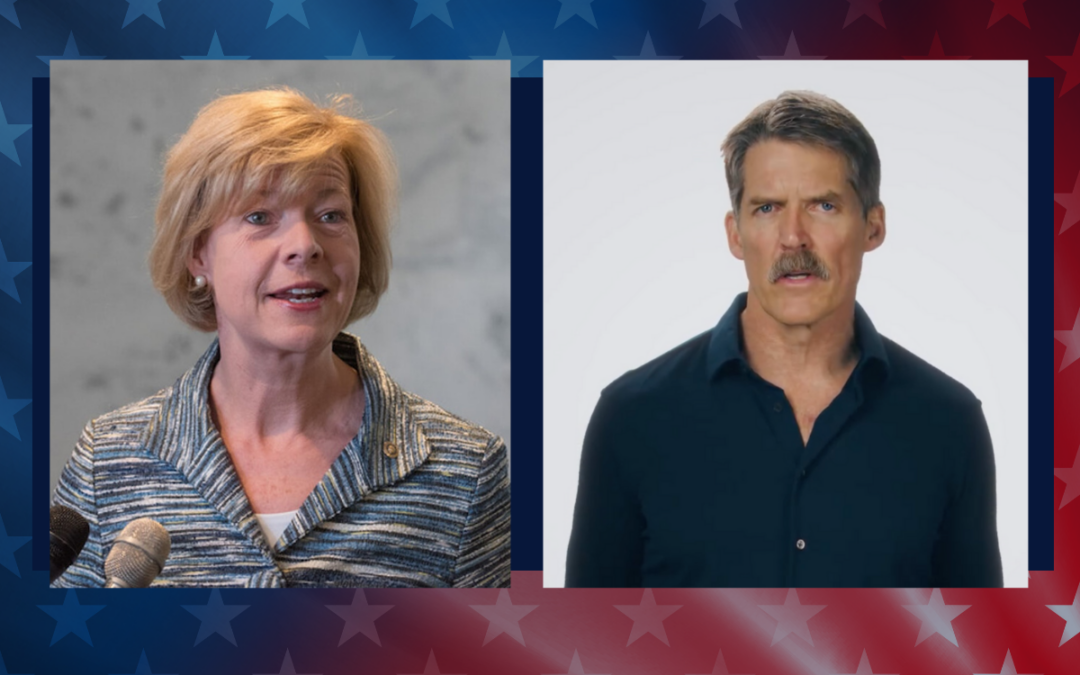

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Who Is Tammy Baldwin?

Getting to know the contenders for this November’s US Senate election. [Editor’s Note: Part of a series that profiles the candidates and issues in...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...