#image_title

#image_title

Jill Underly published two editorials this week addressing the need to face our real history—and to recognize the racial “achievement gap” is really an opportunity gap.

Wisconsin Superintendent of Public Instruction Jill Underly is going on offense—writing a series of editorials calling out critics who intentionally misuse the term “critical race theory” as a way to demand a weakening or ending of lessons about America’s history of slavery, overt racism, and the systemic racism that continues to affect the lives of Black Americans today.

“And that’s a problem,” Underly wrote in the first essay, published Monday

Underly acknowledged that deep conversations about racism will make people uncomfortable, herself included, but that it’s a good thing, “because it means I’m learning and building my understanding of race and racism, and that makes me a better state superintendent. And I want our children, mine included, to know what systemic racism is because they will be more equipped to make our state and our nation not systemically racist.”

Underly said the honest answer is no when asked if critical race theory is being taught in Wisconsin’s K-12 classrooms, because the term applies to an academic field of study at the graduate school level. But if the question is really about whether students should be learning about racial issues and racism, the answer should be yes.

“To do anything else would be a blatant disregard for the truth of our country’s history and an erasure of the lived experience of our students,” she said. “Teaching about race and racism is the only way to teach the complete story of the United States.”

“Teaching about race and racism is essential, it is culturally relevant, it is good teaching, and saying otherwise is not only problematic, it’s racist,” she said.

In her second editorial, Underly tackles Wisconsin’s well-documented history for having some of the broadest racial disparities in the country—something she said cannot be explained away by poverty.

“In fact,” she said, “on average, Black students who are not economically disadvantaged score lower than white students who are. This is the reality of the achievement gap in Wisconsin. It cannot continue this way; we are failing our students of color.”

Underly wants the language about the problem to change because the issue is not an “achievement gap” so much as it is an “opportunity gap.”

“Let’s talk about the gaps in literacy among and between the students who have access to high quality childcare and early childhood programming, versus those who do not. Or … the gap between students with strong mental health care in their schools or communities, compared to those who struggle with challenges and do so without support.”

From the teachers they interact with to the curriculum they learn, students from non-white populations rarely see people like them or hear stories about their contributions to society, Underly said. She called for more culturally relevant teaching (“the original CRT,” she wrote) that nurtures and supports everyone’s cultural identity, embraces and learns from their history, and helps every student feel like they are welcomed and belong in their communities.

Politics

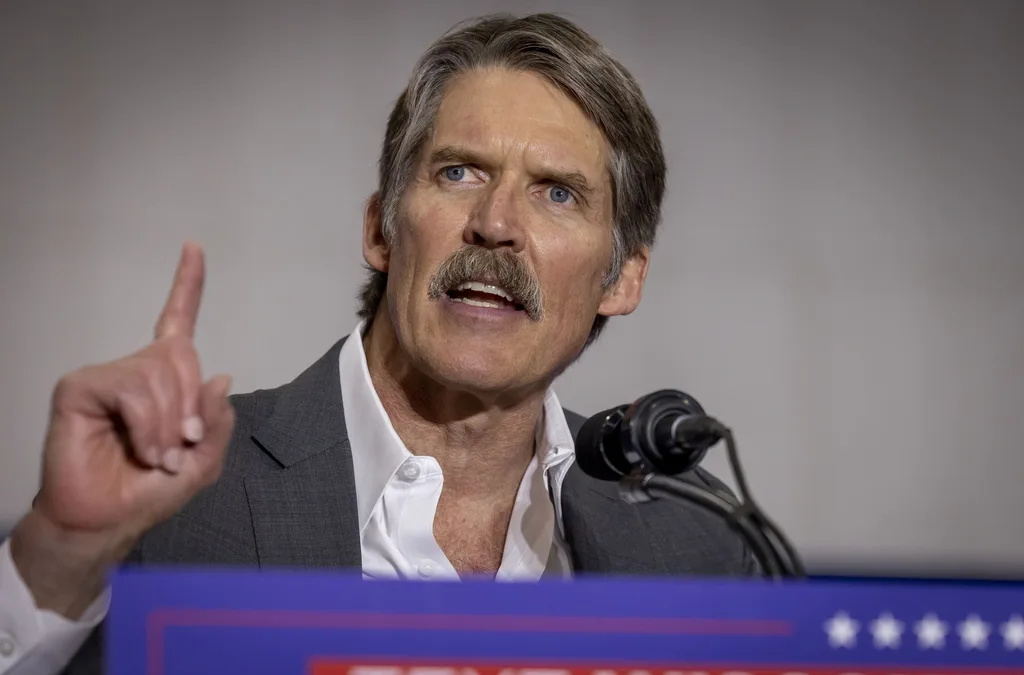

Eric Hovde’s company exposed workers to dangerous chemicals, OSHA reports say

A Madison-based real estate company run by Wisconsin US Senate candidate Eric Hovde settled with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration...

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...