#image_title

#image_title

Efforts to adopt measures endorsing inclusion spark opposition in Marathon County, other Wisconsin communities.

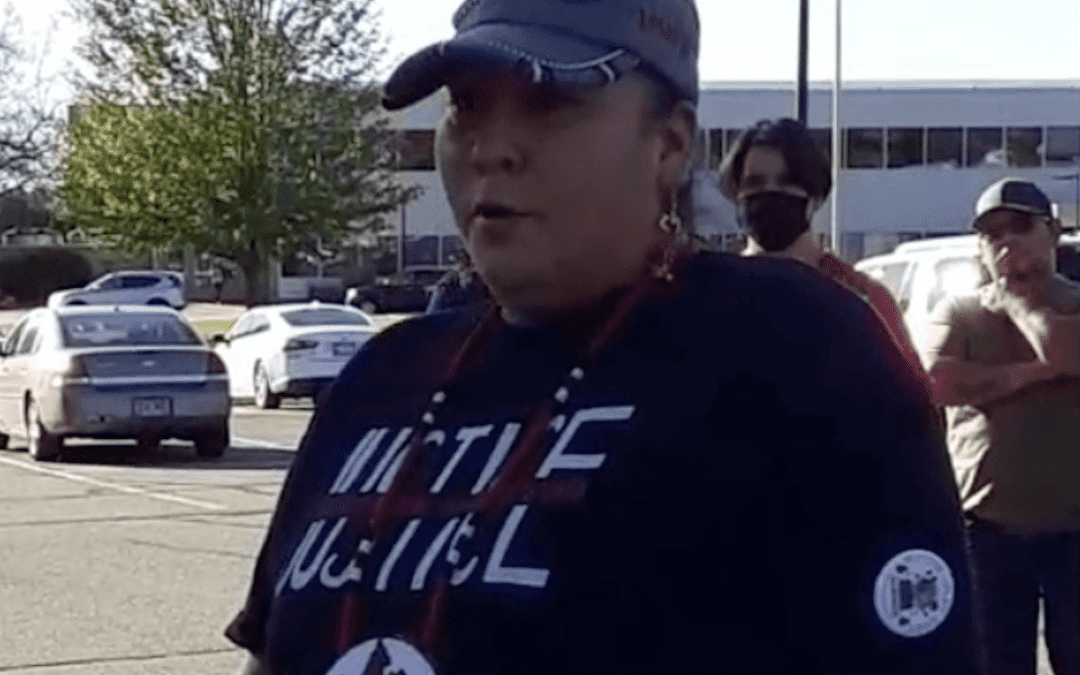

When Yee Leng Xiong proposed a resolution last June declaring Marathon County as “no place for hate,” he intended it as a way to unite the Wausau-area community in the wake of the May 25 killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and the societal schisms that followed.

“At that time there was a lot of anger and hate,” said Xiong, a Marathon County Board supervisor and director of the Hmong American Center in Wausau. “So we decided to be proactive, to get ahead of the curve and release a resolution to try to bring the community together.”

Eleven months and countless meetings and discussions later, the seemingly simple resolution which was amended to declare the county “a community for all” has not been adopted and has instead revealed bitter racial divisions in the central Wisconsin county of 135,000 that is 91% white. Many who live there said the long-standing divide falls largely along political lines and was stoked by former President Donald Trump.

“I never thought this was going to happen, to see all of the opposition to this. It’s very disheartening,” Xiong told UpNorthNews. “The intention was for it to not be controversial in any way, to not be political in any way. But it certainly turned into that.”

On May 13 the county’s Executive Committee voted 6-2 against the resolution, recommending it not go before the County Board. However, on Tuesday, following the publication of a New York Times story describing the inability of the County Board to endorse inclusivity, Xiong joined Wausau Mayor Katie Rosenberg and others in a press conference in which the mayor declared the city “a community for all.”

Wausau “will continue to promote an environment that accepts, celebrates, and appreciates diversity within the community while condemning any hate-based activity, treatment, or discrimination due to a person’s protected class,” the proclamation signed by Rosenberg reads.

Xiong praised the mayor’s action, saying that sentiment is necessary to ensure people of all races and beliefs that they are safe from any racist or hate-related activity. The resolution’s spirit extends beyond race, he said, to differences related to socioeconomic status, sexual preference, and other distinctions between people.

Opponents of the resolution said simply acknowledging racial disparities is a form of racism, and they contend their community is not inherently racist.

“When we choose to isolate and elevate one group of people over another, that’s discrimination,” county Supervisor Craig McEwen told The Times.

Marathon County Supervisor John Robinson said the refusal of some to acknowledge systemic racism makes addressing the issue difficult. Some speakers at last week’s executive committee meeting who opposed the resolution referred to it as socialist or communist and said racism isn’t an issue in the county.

“Some people already feel we’re a welcoming community,” he said. “But there are others who obviously don’t feel that way.”

Following Floyd’s death, community leaders across Wisconsin and the US were forced to confront such topics as social justice, inclusion and diversity. Some communities have adopted new policies intended to address such issues, but others have not yet taken up such measures, and attempts to do so have prompted pushback in some communities. For instance, in Pepin County, a proposal that the County Board consider proposals to address police practices was not even discussed.

“That proposal hit a dead end,” said Bruce Johnson, co-chair of the Pepin County Democratic Party. “There really wasn’t a willingness, even on the part of progressives, to spend political capital on that topic. They just said ‘it isn’t going anywhere.’ ”

Similarly, efforts to designate Martin Luther King Day a holiday for city workers in Superior and an effort to rename a local road in northern Wisconsin to honor the history of indigenous people of that region elicited opposition from residents, said Shawnu Ksicinski, executive director of the progressive voter education organization Progress North, which covers five counties in the northern part of the state.

“When we have county and city governments proclaiming they’re inclusive and welcoming of people of color, but refusing to pass resolutions and policy that reflect that, there is a clear disconnect from what inclusivity and equity actually mean,” she said.

Supporters of efforts to make people of all sorts feel more welcome in communities said doing so is especially challenging in many rural areas populated nearly entirely by white people. Pepin County, a small county in western Wisconsin that borders the Mississippi River, is 98.9% white, and many who live there don’t believe racism exists where they live, Johnson said.

Last summer Johnson and others attended three Black Lives Matter protests in Pepin County, including one in support of a Black girl who was the target of a racist act while working at a restaurant. Those events were signs of support for inclusion, he said, but also evidence that work remains.

RELATED: Racists May Feel Emboldened, But This Wisconsin Town Showed the Power of Love

“Most people don’t want to be racist. They just don’t understand that systemic racism exists even where they live,” Johnson said. “Overcoming that is our challenge.”

During debate of the inclusivity measure in Marathon County, some county supervisors said such topics “are a Wausau issue, not a rural issue,” Xiong said. “But diversity doesn’t die at the borders of Wausau. Those beliefs and attitudes matter everywhere,” he said.

The Marathon County diversity affairs commission is scheduled to review an amended version of the resolution on May 26, Xiong said, and the County Board could vote on it next month. He is hopeful it can muster more support between now and then, but he acknowledges challenges.

“Racism is certainly a problem here,” Xiong said. “Yet we can’t address those issues if we can’t even acknowledge there is a problem. I’m hoping we can get to that point.”

Politics

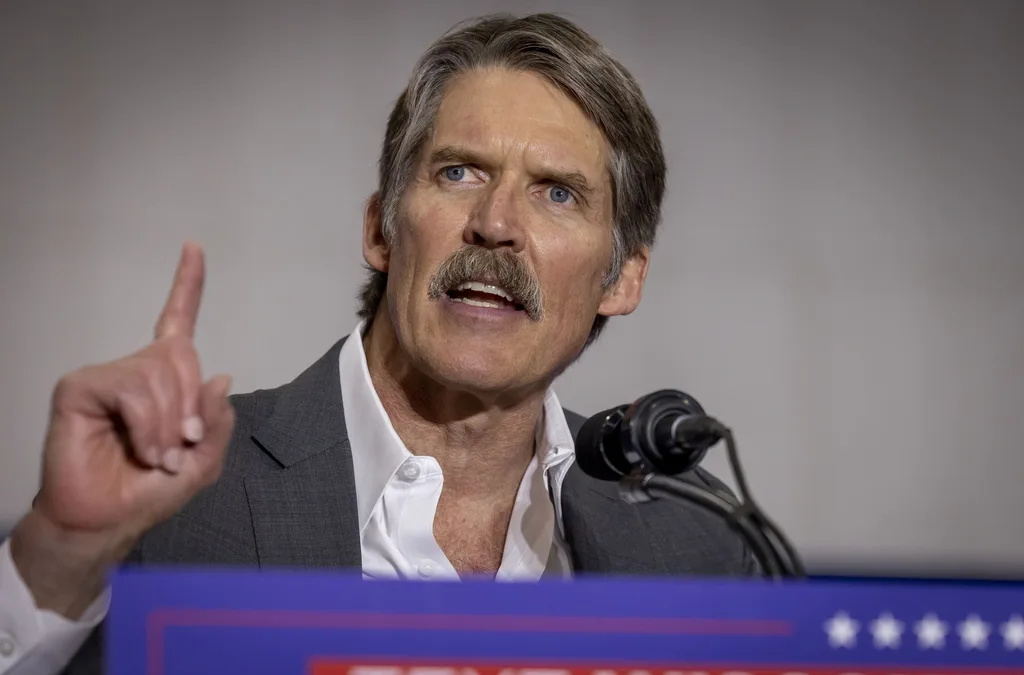

Eric Hovde’s company exposed workers to dangerous chemicals, OSHA reports say

A Madison-based real estate company run by Wisconsin US Senate candidate Eric Hovde settled with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration...

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...