#image_title

#image_title

With high costs and low profits, families, providers, and the economy as a whole need the system to change.

If there’s been one silver lining to the pandemic for Anne Alexander of DeForest and other childcare providers, it’s that after so many years of being underfunded and underappreciated, politicians and the public are finally talking about how important their industry is.

“It’s certainly helping that, I think for the first time ever, the word is getting out how essential child care [is],” Alexander said. “Because of the pandemic, I think people are finally taking notice.”

Earlier this month, Vice President Kamala Harris visited a childcare center in Annandale, Virginia and announced that $39 billion in American Rescue Plan funds will go to states, tribes, and territories to help childcare centers reopen or stay open.

“The strength of our country, the resilience of our economy depends on the affordability and availability of child care,” Harris said. “Even before the pandemic, childcare cost too much, and it was too hard to find, and for too many families, outside of their reach. The pandemic has accelerated the flaws and the fissures in our systems.”

Alexander, owner of Wee Care Family Child Care in DeForest, has been a licensed child care provider for 28 years, which meant she had a little bit of savings to help when she closed from March to July in 2020 because she was concerned about contracting COVID-19. But not many other child care providers could do the same.

“As a childcare provider, some of us (I think a lot of us) don’t have a lot of cash reserves,” Alexander said. “It’s hard to do that on the amount of money we make.”

A pre-pandemic study from the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment found that while most Wisconsin families are paying an average of $12,268 per year for infant care (which is $3,793 more than the average in-state college tuition) and $9,954 for toddlers and four-year-olds, the poverty rate for early childhood educators is 19.7%, twice the poverty rate of Wisconsin workers in general.

Alexander said the high cost and low profit is caused by a number of factors, including ten-hour days, educational materials and equipment, snacks and meals, required training, licensing fees, and joining professional organizations. Her administrative tasks—like interviewing parents, advertising, and making sure her business is in compliance—contribute as well, she said.

“And you have to do that when kids aren’t with you so that makes our days even longer,” Alexander said. “So when you add up how many hours we’re working to do all those things, it ends up being that much per hour. And if you just do the bare minimum, just become licensed and just provide a safe environment that is less expensive, right? But that’s not quality.”

And as studies have shown for decades, quality in early childhood education has an outsized impact on student achievement. Children who have some preschool experience will later have higher standardized test scores, are 11% more likely to graduate high school, and are less likely to be held back or placed in special education programs, and reached higher levels of tertiary education, even when they came from families with lower educational attainment. A longitudinal study of children given preschool education in Chicago in the 1980s found they were 48% more likely to complete an associate’s degree, and 74% more likely to complete a bachelor’s degree or higher by the time they were 35 years old.

And despite the global pandemic, childcare providers have continued to invest in providing quality child care for their children. Alexander said she’d been looking into doing nature-based programming for some time and while she was closed, she decided it was time to go all-in. She bought equipment made of natural materials for climbing, exploring, and play. Her fiance built an outdoor hand washing station; and when she reopened in July, the kids spent most of the day outdoors, even during their naps.

“I thought they’d be distracted or want to play, but they rested so well outside in the shade and the birds were chirping,” she said. “And I would read my book while they were napping and it was, it was wonderful.”

Corrine Hendrickson in New Glarus made a similar change. She closed down in March when the Safer at Home order was issued and invested in moving her operation outdoors with things like a portable hand washing station, rain suits and rain boots, and outdoor play equipment. Kids only come inside to use the restroom or to take their naps if the bugs are bothering them too much.

Pre-pandemic, Hendrickson’s home-based childcare center, Corrine’s Little Explorers, was doing pretty well. Through creative scheduling, she’d managed to finagle 15 children (some only half-days) at her care center, which is licensed for children ages six weeks to 11 years. But after all of the expenses, she calculated her hourly wage was $11 an hour, without benefits.

RELATED: Biden’s COVID-19 Relief Puts Money Into the Pockets of Wisconsinites Who Need It

Even with her new programming and precautions, she now only cares for eight children. In part this is because she’s hesitant to take on new clients if she’s unsure they’ll take precautions at home to prevent spreading the virus to her and the other children. Hendrickson said that if it weren’t for the assistance she received from the federal and state government, through the Paycheck Protection Program, and childcare grants the Evers administration created with state CARES Act funds, she estimates she would have earned $10,000 last year.

A National Association for the Education of Young Children survey of 6,000 child care providers nationwide found: 81% have fewer children enrolled; 56% said they lose money every day that they open; 51% said they could only survive three more months under the status quo; and one in four said that if enrollment stays where it is, they will have to close permanently within three months.

For those that remain open, particularly large child care centers, employee retention has become an issue. While it’s hard to know how many centers have closed permanently, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found 166,900 fewer people worked in child care in December 2020 than the previous year.

Kyra Swenson of Fitchburg is one of them, even though she was relatively lucky. She worked for 11 years at a child care center that was sponsored by area employers and paid her $16.50 an hour and offered benefits, such as health insurance and a 401K, “which is almost unheard of in our field.” Even with that high pay, employee retention was an issue.

“I could’ve gotten paid $15 an hour down the street at Kwik Trip and have had a much lower stress, a much easier job, and one that didn’t require a college education,” she said.

Because many of the staff at her center had attained some degree of higher education, the biggest pull was the public school system, where they could earn double what they were earning at the center. But Swenson stayed for so long because she loved her job.

“I loved my coworkers, I love my kids and families. I was really in the place that I wanted to be as far as my career was concerned,” she said. “I would still be working there if it hadn’t been for the pandemic.”

In the early days of the pandemic, she felt that the child care industry wasn’t being prioritized for personal protective equipment. Swenson has had pneumonia three times. Her husband was working for a health system handling COVID-19 data and saw how many people were being hospitalized, put on respirators, and dying.

“He became very concerned that I was going to end up as one of those statistics,” Swenson said. “And so it became this question of, am I going to prioritize my health and my family or my career?”

When her children’s school started discussing going virtual or hybrid, she decided she would quit her job and stay home with them.

She’s not alone; multiple studies have found that women have dropped out of the workforce at higher rates during the pandemic. The National Women’s Law Center found that between August and September 865,000 women dropped out of the workforce, compared to 216,000 men. A disproportionate number of those women were Black or Latina. An analysis from the progressive Center for American Progress estimated that 700,000 women left the workforce during the pandemic.

The next chapter in this series will look at how child care access affects women’s careers, finances, and the economy as a whole.

Politics

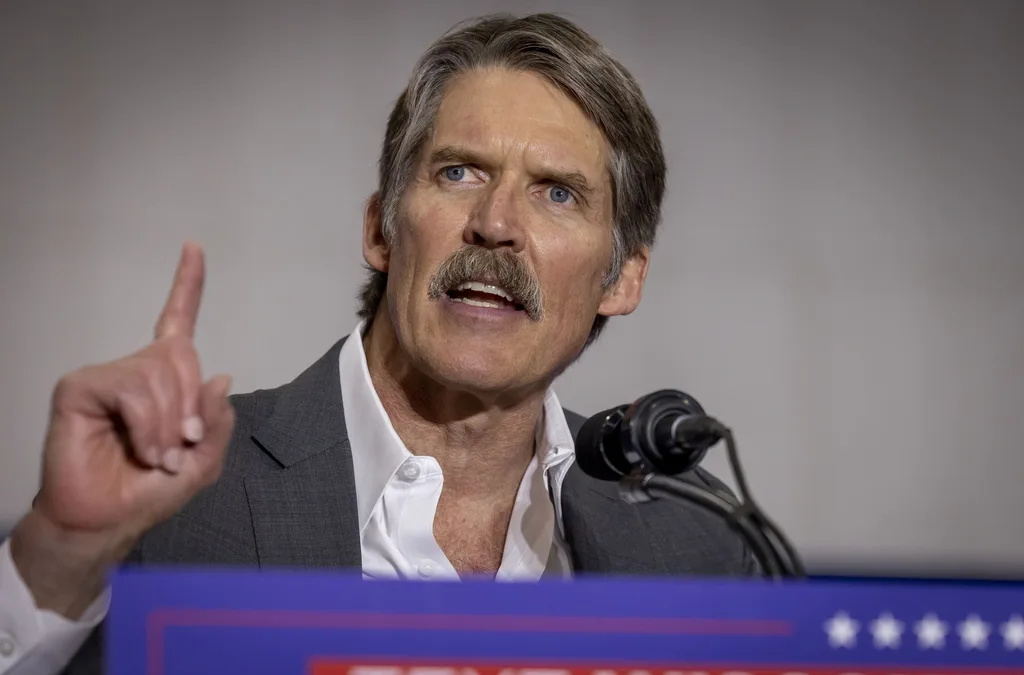

Eric Hovde’s company exposed workers to dangerous chemicals, OSHA reports say

A Madison-based real estate company run by Wisconsin US Senate candidate Eric Hovde settled with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration...

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...