#image_title

#image_title

Despite population loss, community organizers spur a boost in turnout.

An outsider might think Milwaukee’s election results were a disappointment for local left-leaning organizers.

After all, Milwaukee voters cast 141 fewer ballots in 2020 than 2016, President-elect Joe Biden received a modest-at-best 2% improvement over Hillary Clinton while many of the city’s suburbs saw massive shifts toward Biden, and many majority-Black or Latino voting wards saw small yet surprising shifts toward Trump. But a deeper look at key context reveals how remarkable the city’s turnout was as Wisconsin broke away from President Donald Trump and delivered its 10 electoral votes to Biden by a margin of about 20,500 votes.

“I’m still so incredibly proud of everyone that threw down in this election,” said Angela Lang, executive director of Black Leaders Organizing for Communities, an organization that mobilizes Black voters on Milwaukee’s north side.

Milwaukee had about 315,500 registered voters for the Nov. 3 election, a drop of roughly 13,000 from 2016, city records show.

That’s partially reflective of population loss, particularly on the predominantly Black north side, and partially attributable to fewer college students living on-campus, according to John Johnson, a research fellow at Marquette University’s Lubar Center for Public Policy Research and Civic Education. The US Census Bureau estimates Milwaukee’s population at about 590,000, a drop of about 5,000 from 2016.

So while the total number of votes cast barely budged—dropping from roughly 247,800 to about 247,700—turnout as a percentage of registered voters actually grew 3 points, jumping from 75.5% to 78.5%.

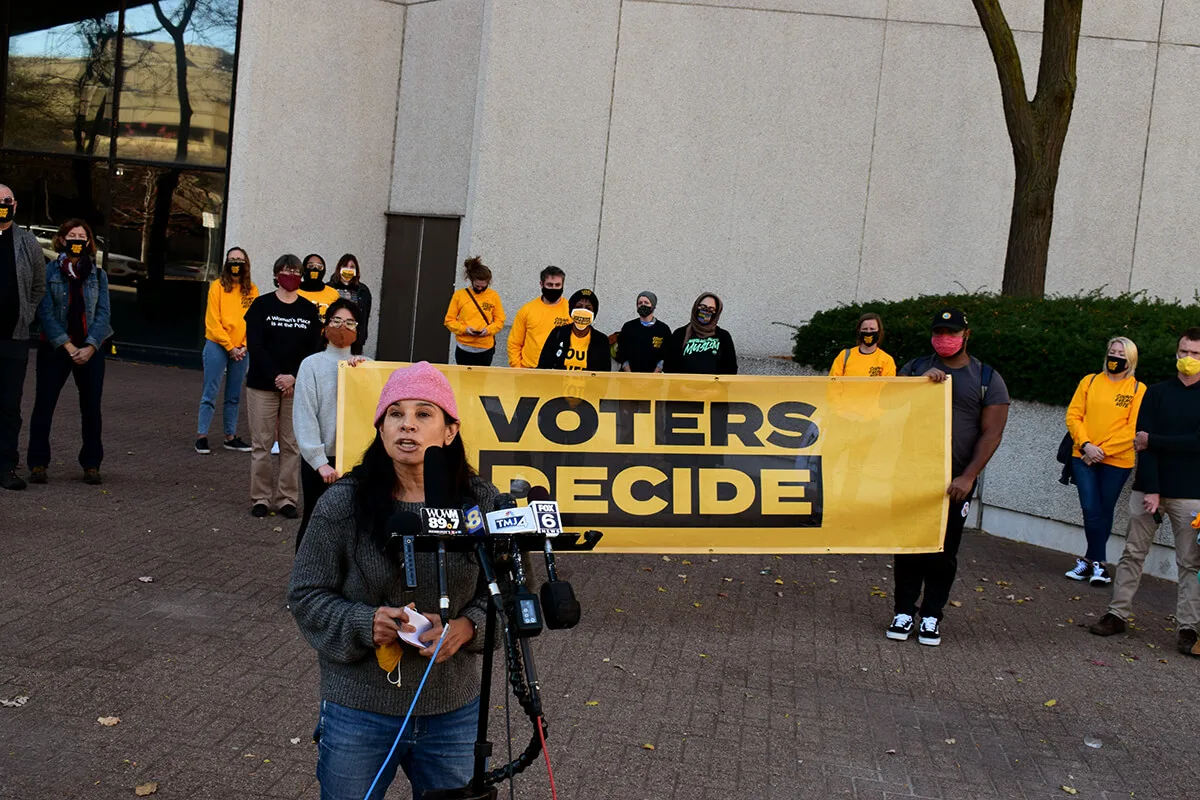

That solid improvement represents a more engaged and informed electorate helped along by groups like BLOC, Leaders Igniting Transformation (LIT), and Voces de la Frontera Action, which collectively made millions of voter contacts in Milwaukee’s communities of color for the 2020 presidential campaign.

Voces made about 820,000 contacts with Latino voters this year in some of the state’s most heavily Latino areas, such as Milwaukee’s south side; BLOC made over 822,000 voter contacts between calls, texts, and door-knocks; and LIT made about 3 million contacts by phone and text, and ran digital ads that received about 2.8 million impressions.

“We see it as a tremendous success,” said Christine Neumann-Ortiz, executive director of Voces de la Frontera.

Lang pointed out that Milwaukee’s voters of color had to overcome a huge amount of hardship in this election cycle. COVID-19 hit the city’s Black and Latino populations hard early on in the pandemic and never let up. Demonstrations for racial justice that began after George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police continue to this day.

An investigation revealed in late September how the 2016 Trump campaign used micro-targeted social media ads to deter people of color from voting, and there was no indication the president’s re-election campaign wasn’t reusing the tactic. Wisconsin’s strict, Republican-enacted voter ID law that disproportionately makes it harder for people of color to vote is still in place.

“We were dealing with just an incredibly tremendous amount of trauma and tragedy this year,” Lang said.

Some of those details may have contributed to shifts toward Trump in many majority-Black wards on the north side and majority-Latino wards on the south side.

Johnson published interactive maps showing some of these shifts. In many north side wards, population dropped significantly, but turnout was higher than 2016 among registered voters who remained. Trump gained just a handful of votes in many of these areas while Biden lost a significant amount.

For example, in Ward 152 in the city’s Metcalfe Park neighborhood, Biden received 332 votes, a decrease of 36 from Clinton; Trump’s vote share barely grew, from 12 votes to 19 votes, but the drop in Biden’s votes resulted in a 4-point swing to Trump. There were 136 fewer registered voters in the ward in 2020, yet 9% more registered voters cast a vote than in 2016.

“We’ll have a much better sense of [what caused] this after the 2020 Census data is released,” Johnson said. “But based on the estimate we do have right now, that seems like the most likely explanation. There’s actually just fewer people living there.”

However, the south side appears to be a different story, with little to no population loss, a slight drop in turnout, and a shift toward Trump. Biden still handily won all these wards, typically by margins of 50% or more, but his performance was poorer than Clinton’s.

Johnson overlaid the voting wards with the city’s aldermanic wards and found a significant red swing in aldermanic wards 8 and 12. In Ward 8, which is 70% Latino, Biden’s margin of victory was 56%, 7 points worse than Clinton. In Ward 12, which is 71% Latino, Biden’s margin of victory was 60%, an 8-point slide from Clinton. Clinton similarly underperformed in these wards compared with Barack Obama in 2012; she fell 5 and 6 points in wards 8 and 12 respectively.

Neumann-Ortiz said she thinks those sorts of shifts may be attributable to a stronger turnout from white voters in the wards.

“I wouldn’t necessarily conclude the shift to red is coming from Latino voters in that district,” Neumann-Ortiz said. “I think it’s premature to make that assumption, especially when we see a historic turnout [statewide] and we know that the vast majority of Latino voters voted for Biden.”

However, Johnson’s analysis found “modest improvements” for neighboring majority-white wards, a trend seen across the city in majority-white areas that he attributed to a lack of a strong third-party candidate.

But Johnson cautioned the raw voter data he examined has no way of determining the efficacy of groups like Voces, LIT, and BLOC.

“It’s not possible for me to judge anything about that,” he said.

Cree Myles, digital media manager for LIT, echoed Neumann-Ortiz’s sentiment that it’s too early to interpret much deeper meaning from the raw data. She said the 2020 results show “absolutely there’s room for improvement,” not just in cities, but everywhere in Wisconsin.

“Honestly, white people in the suburbs put us in this mess in the first place, so they should be the people who overcorrect,” Myles said.

And at the end of the day, Milwaukee still contributed a net 3,000 votes to Biden versus 2016, despite having fewer people living in the city. Lang said it’s a win, no matter what.

“If we weren’t here, maybe Wisconsin wouldn’t have went the way that it did, we weren’t able to flip it back,” Lang said. “And so I think everyone’s assessment initially is that every single tactic, every single text message, every single phone call worked in a sense.”

Politics

It’s official: Your boss has to give you time off to recover from childbirth or get an abortion

Originally published by The 19th In what could be a groundbreaking shift in American workplaces, most employees across the country will now have...

Trump says he’s pro-worker. His record says otherwise.

During his time on the campaign trail, Donald Trump has sought to refashion his record and image as being a pro-worker candidate—one that wants to...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...