#image_title

#image_title

Where the march for social justice confronts the hurdles of forming new policy.

While Republican legislative leaders in Wisconsin have let calls for police reform go unanswered this summer in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and the shooting of Jacob Blake by Kenosha police, several cities in the state have taken action or begun steps toward reforming their law enforcement agencies, with varying degrees of progress.

No Wisconsin city officials have taken as radical a step as Minneapolis’ City Council, which pledged but ultimately failed to dismantle its police force in 2020. In fact, officials in most cities and towns in Wisconsin have done nothing to address concerns. But during the summer and early fall, at least one Wisconsin police chief was demoted, several cities have banned chokeholds, and others are playing catchup as they scramble to meet the ever-growing demand for officers to wear and use body cameras.

“We wanted to view the summer as a chance to, while everyone’s attention was on these issues, to engage as many residents as possible,” said Vicky Selkowe, manager of strategic initiatives and community engagement for the city of Racine.

Racine, led by Democratic Mayor Cory Mason, was among the first Wisconsin cities to jump on the police reform trend. First, Mason enrolled the city in the Government Alliance on Race and Equity and held community conversations in which 225 people participated, Selkowe said.

Aldermen in Racine then hired a consulting firm to guide a process of reform and voted to create a new city website wholly dedicated to the city’s police-reform efforts. The website, RacinePoliceReform.org, includes links to PDFs of over 300 Racine Police Department policies, including use of force, and hosts an anonymous community survey that anyone can fill out.

Mason also led the Mayor’s Task Force on Police Reform, which held five meetings over the summer and included community leaders and activists. Racine Police also spent a week undergoing training with the RITE (Racial Intelligence Training & Engagement) Academy.

Mason said during the final task force meeting he will get reports and recommendations based on the community survey, community conversations, and task force conclusions in mid-October. From there, he said, he will pass the reports on to the city’s Affirmative Action and Human Rights Commission, which will make recommendations to the full Common Council.

“Some [reforms] will be things that we can just immediately implement, and if that’s the case, that’s what we’ll do,” Selkowe said. “Some will require ordinance change or policy change, and those might go to the council for approval.”

Milwaukee, already reeling from a local police officer, Michael Mattioli, being charged with murder in the killing of a Latino man, took action shortly after Floyd’s death. The Common Council in June directed the city’s Fire and Police Commission to develop a police department policy for what officers should do when a suspect says “I can’t breathe,” and followed that directive up with telling the city budget director to propose a 10% cut to the police department’s $300 million budget.

Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett presented a 2021 budget proposal late last month that would cut 120 police office positions, but not decrease funding to the department, a decision he chalked up to inflating salaries and benefits costs. In an interview with UpNorthNews, Common Council President Cavalier Johnson defended the proposal despite his previous support for the potential 10% cut.

“The council’s action in passing a resolution earlier this summer was for the budget office to present a model 2021 budget for the police department, about what it could look like to reduce 10% from the police department budget,” Johnson said. “It was never that for sure 10% of the budget was going to come out of the department in 2021.”

For other reforms, the Common Council can only make requests and act as a voice for them. Many reforms, including the “I can’t breathe” policy, can only be made by the Fire and Police Commission. Among other reforms the Common Council requested were a policy requiring a report every time an officer draws a weapon, including a Taser or pepper spray; a database of badge numbers of police officers and firefighters; and more diversity in hiring.

The Fire and Police Commission has taken no action on the Common Council-requested reforms. Johnson appeared frustrated with the lack of progress.

“It’s upon the Fire and Police Commission to respond and enact those,” Johnson said. “We’ve listened to the voice of people in our community, we’ve put forth policies, but we can only do so much.”

That’s not to say the commission did not act at all in recent months. Commissioners unanimously voted in August to demote now-former Police Chief Alfonso Morales over his department’s violent handling of Black Lives Matter protests and his refusal to fire Mattioli, the officer charged with murder. Morales retired soon after and said he might sue the city.

Johnson added the state Legislature is one of the biggest inhibitors to substantive change. Assembly Speaker Robin Vos (R-Rochester) and Senate Majority Leader Scott Fitzgerald (R-Juneau) have not convened their chamber in almost six months, even as calls for police reform grow and the coronavirus pandemic rages.

Wauwatosa has also taken some steps toward police reform, even as it sought to clamp down on protests against police brutality in August. The western Milwaukee suburb has faced intense scrutiny over one of its police officers who killed three people in the last five years; the Common Council wants the officer, Joseph Mensah, fired. The Police and Fire Commission suspended him with pay pending further hearings.

Police in Wauwatosa are on track to get body cameras by the end of the year, a key tool for accountability. The Common Council also voted in August to ban chokeholds, a tactic that resulted in the death of Eric Garner, an unarmed Black man, in New York.

Still, progress in Wauwatosa has been met with resistance beyond the attempt to restrict protests. The local police union last month called for the city’s commission on police reform to be disbanded because the commission’s chairman is a member of The People’s Revolution protest group. The police chief also wanted the head of the city’s Equity and Diversity Commission to be removed because he demanded Mensah’s firing.

In the wake of Floyd’s death, rather than circle the wagons and defend policing tactics, Eau Claire police Chief Matt Rokus decided to listen to what community members had to say about his department.

“We really focused on listening to the community’s concerns,” Rokus said. “We realized that to have the trust of the community, we need to go out and interact with community members, to hear what they have to say, even if it is critical, and to be transparent.”

Eau Claire police already were practicing some of the measures police reform advocates are calling for, but discussions between Rokus’ department and citizens have resulted in more than 20 reforms that emphasize training, de-escalation strategies and improved communication. Among them are banning chokeholds, strictly limiting no-knock search warrants and moving up funding to purchase body cameras for officers.

Rokus praised his officers for their willingness to adopt new policing approaches and said community partnerships are necessary for those efforts to occur. He acknowledged some people still have negative perceptions of police and are afraid to interact with officers. He hopes continued efforts by his department to develop dialogue with more city residents will transform that apprehension to trust.

“We have a choice. We can say everything is fine, and we don’t need to change anything,” Rokus said. “Or we can do the right thing and continue our commitment to continual improvement and respond to the concerns we heard. We’re choosing to take the latter approach.”

Police reform efforts also are being discussed in Wausau, where a mayor’s task force on the topic met for the first time last week. Mayor Katie Rosenberg said she was prompted to form that group after a June 6 Black Lives Matter march in her city attracted nearly 2,000 participants.

“I was being asked to act on this topic,” Rosenberg said, “and I realized that while our police department was already doing a lot of what was being recommended, we needed to discuss this issue further, to see what more we could be doing and to build trust in police in our community.”

Wausau police Chief Benjamin Bliven said his department has implemented multiple changes in the past couple of years intended to build more partnerships and de-escalate potentially dangerous situations. Chief among them, he said, is assigning and training one city and one Marathon County police officer to a mental health team that responds to crisis calls.

Many police calls involve an aspect of mental health, and the mental health crisis team has significantly reduced dangerous situations, Bliven said, while also providing improved care for people undergoing mental health struggles.

“We are trying to better understand the mental health needs in our community and provide better care for those people who need it,” he said.

His department will discuss adopting further changes to its operational policy in upcoming months as the task force continues to meet, Bliven said. Chief among the department’s tasks is community outreach to dispel adverse feelings toward police by some citizens.

“We’re not perfect,” Bliven said. “We sometimes make mistakes and sometimes don’t see things as well as we maybe could see them. We have to be willing to listen, willing to have difficult conversations if we want to be worthy of people’s trust.”

In liberal stronghold Madison, a recent community survey found residents were divided on how to reform the police over the next two to three years. That two- to three-year timeframe was chosen because the city is hiring a new police chief, so the survey was used as a way to gauge what residents feel the new chief should do when they take over.

Fewer than half of the respondents, about 45%, said the department should be demilitarized, while less than a third, about 32%, said the department’s culture should be changed, according to the Wisconsin State Journal. Just over 59% said the department needs to build more trust with the community.

Madison’s Common Council also voted last month to establish a Civilian Oversight Board, which will have broad access to police records but lack the power to hire or fire officers. The board will, however, be able to hire someone to fill the newly established independent police monitor position for the city.

Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway announced the first round of nine appointees to the oversight board on Friday, with each of them sponsored by a different community organization. Rhodes-Conway came under fire and apologized in June after someone leaked a private video she made to praise police officers’ actions during Black Lives Matter protests.

While it has not yet taken action, leaders in Kenosha have pledged to enact reforms following the Aug. 23 shooting of Blake. Kenosha County Executive Jim Kreuser and Mayor John Antaramian have promised to include money for police body cameras in the next county and city budgets.

Kenosha County Sheriff David Beth, a Republican who recently endorsed President Donald Trump for re-election, said in August he was “open to making whatever changes we can.”

Antaramian is holding a series of community listening sessions on systemic racism in Kenosha, and said last month “it’s gonna be my responsibility to make sure we’ve changed.”

Politics

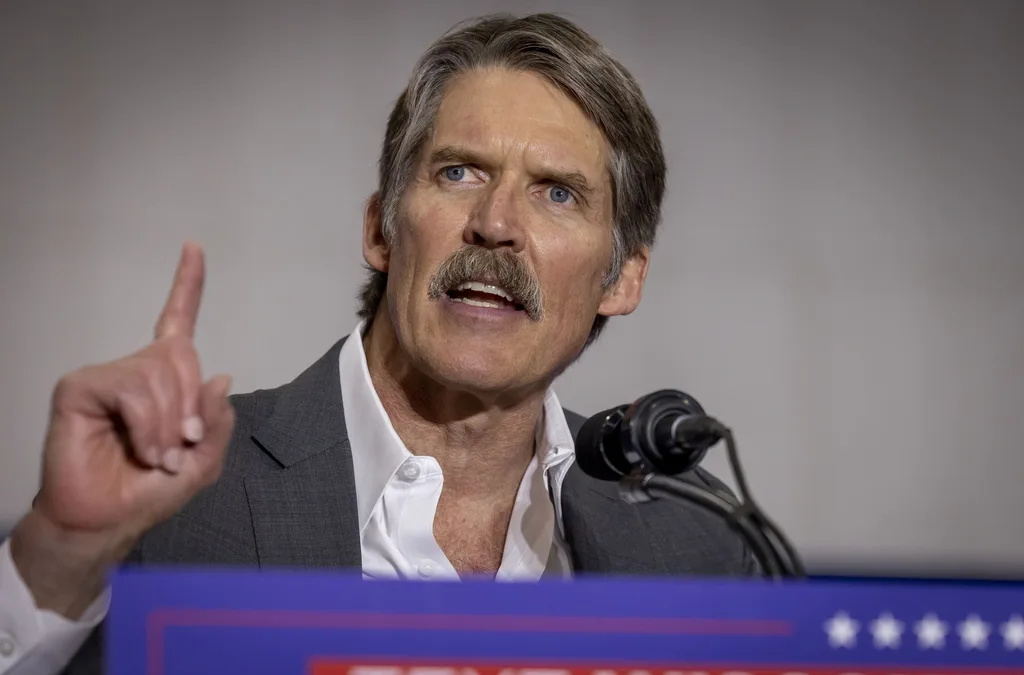

Eric Hovde’s company exposed workers to dangerous chemicals, OSHA reports say

A Madison-based real estate company run by Wisconsin US Senate candidate Eric Hovde settled with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration...

Plugged in: How one Wisconsin school bus driver likes his new electric bus

Electric school buses are gradually being rolled out across the state. They’re still big and yellow, but they’re not loud and don’t smell like...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...