#image_title

#image_title

State was first to ratify the 19th Amendment, but suffrage didn’t come without a long battle and many setbacks.

Bells will ring out across Wisconsin at noon on Aug. 26 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote nationwide with the adoption of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Wisconsin was the first state to ratify the amendment on the morning of June 10, 1919, but the Amendment needed approval from legislatures in 36 states, an achievement bestowed by Tennessee lawmakers on Aug. 18, 1920. U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby certified the results that made the Amendment official on Aug. 26.

Despite the honor of being first to ratify, Wisconsin was actually behind many other states in treating women as equal to men, experts on the women’s suffrage movement said.

First Lady Kathy Evers, head of the centennial committee, has asked people to wear white on Aug. 26, a color the suffragists wore in their marches a century ago.

“I’m really proud that Wisconsin was the first state to ratify,’’ said Rep. Shelia Stubbs, Dane County’s first Black legislator and a member of the 19th Amendment centennial committee. “But I also want to talk about this moment in history because it did not include Black women. It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act (of 1965) that truly guaranteed our right to vote.”

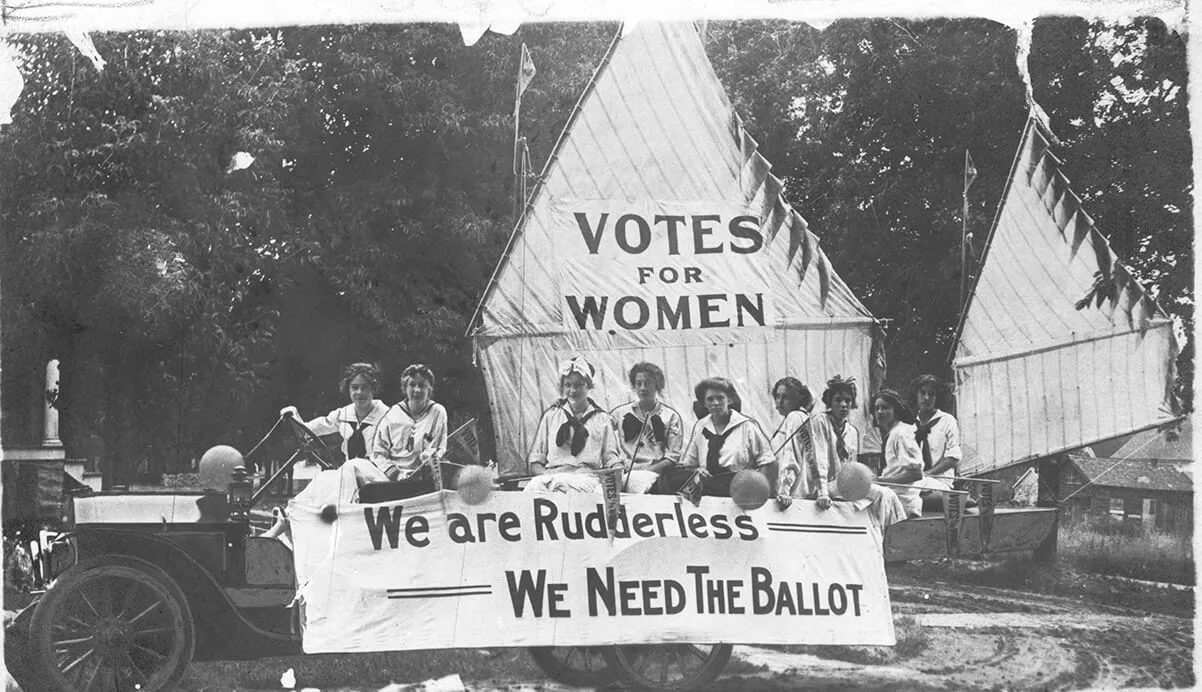

Before adoption, Wisconsin men had held women back from the ballot box for decades.

In fact, Wisconsin was only first for reasons beyond the core issue: a laggard 1919 Legislature that hadn’t finished its budget on time, politicians who changed their votes at the last minute to cover their rear ends in case the federal law passed, some shoddy bill writing by Illinois lawmakers who otherwise would have been first, and road and rails race to Washington with the formal documents of ratification.

“The fact that Wisconsin ratified first is not a coup for so-called ‘Progressive Wisconsin,’ “ said Genevieve McBride, an emerita history professor at UW-Milwaukee and author of “On Wisconsin Women: Working for their Rights from Settlement to Suffrage.”

McBride argues that the paradox of Wisconsin ratifying the 19th Amendment before other states is precisely because women here were still organized and lobbying hard for their rights to vote long after other states had let women into the voting booth. Between 1899 and 1915 there were 21 failed attempts in the Wisconsin Legislature to secure women’s suffrage. In 1912, Wisconsin women suffered another crushing defeat when men voted in a referendum 2 to 1 to deny them the right to vote.

“That vote made Wisconsin infamous among women nationwide,’’ McBride said, noting the liquor lobby, fearing that women would vote against alcohol, pushed for the 1912 defeat. Adding to the insult, the referendum vote was recorded on pink ballots.

The push for voting rights actually predated statehood, but when Wisconsin entered the union in 1848, only white men and Native American men who renounced their tribes could vote. Following the Civil War, Ezekiel Gillespie, a Black man from Milwaukee, sued for the right to vote and won in the Supreme Court in 1866.

Women’s suffrage groups formed around the state, from Richland Center to Kenosha in the 1850s, but women’s voting rights took a backseat to abolitionist activities. Following the Civil War, the first suffrage convention was held in Janesville in 1867.

Decades of struggle resulted in Wisconsin women briefly gaining the right to vote in 1886. The Rev. Olympia Brown of Racine, who was president of the Wisconsin Women’s Suffrage Association, sued when denied the right to vote, hoping the courts would uphold the law. Instead, the state Supreme Court threw out the law on a technicality.

Meanwhile, western states were entering the union and giving women the right to vote. Wyoming was the first in 1869. By 1916, Montana had sent the first woman, Rep. Jeanette Rankin, to Congress.

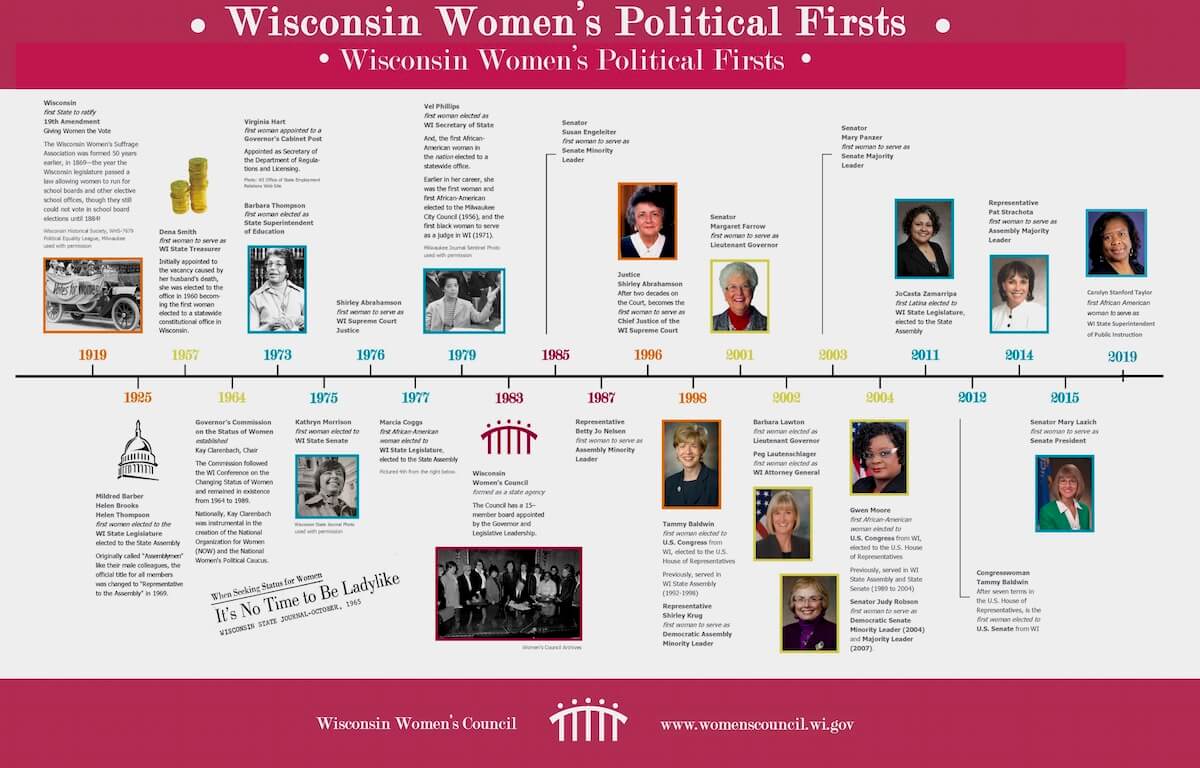

“Wisconsin was also extremely backward when it came to electing women to office,’’ McBride said, noting that it was not until 1999 that Wisconsin had its first female congressperson, Tammy Baldwin, now a U.S. Senator. Until Baldwin won an open seat in the 2nd Congressional District, Wisconsin was the last state to have neither elected a female governor nor a female federal representative nor a senator.

Finally in 1902, women won “partial suffrage,’’ which gave them the right to vote in school elections only.

So, what changed in 1919? For one thing, Wisconsin feminists had been waging a fierce battle, including a statewide public relations blitz by Waukesha Freeman journalist Theodora Winton Youmans with support from Wisconsin first lady Belle Case LaFollette.

For another, it was one of the only states with a Legislature still in session. (“Then, like now, they had trouble finishing their business,’’ McBride says.) It meant Wisconsin benefited from good timing as Congress had recently given final approval to the Amendment — the House of Representatives on May 21 followed by the Senate on June 4. Illinois lawmakers were also still in session and actually ratified the 19th Amendment about an hour before Wisconsin’s vote, but their resolution wasn’t worded correctly. Richland Center’s Ada James made sure the Wisconsin ratification was worded properly.

Once it passed, McBride said James “commandeered” her father, former state Sen. David James, who happened to be in Madison for a Civil War reunion, and had him take the precious paperwork by car and train to Washington, D.C.

And that is how Wisconsin was first of the 36 states needed to ratify. McBride said rather than being another piece of Progressive policy, it was the end of decades of exhausting struggle by generations of Wisconsin women. It was a struggle that still left other women behind.

Black suffragists, including the journalist Ida. B. Wells-Barnett, were famously told to march at the back of a voting rights march on Washington in 1913. And in 1920, when women could first vote all across the country, many Black women, especially in the South, were harassed by poll taxes and tests that made it difficult to vote.

Charmaine Lang, a doctoral candidate in African and African Diaspora Studies at UW-Milwaukee, studied the role that Black women’s clubs played during the suffragist era.

“The reason the Black women’s club movement existed was that the white women were not allowing Black women in their clubs,’’ Lang said. “They were active, voting rights was one pillar of their work, but they were also known for work uplifting the race, on human rights, and work to protect the virtue and rights of Black women. They were led by Black women who were educated, degreed, and spoke multiple languages.”

Rep. Stubbs knows that history, too. Her Delta Sigma Theta sorority, including national leaders like Dorothy Height, campaigned for Black women’s voting rights, a campaign that also took place in Black churches.

Her grandmother in Arkansas was the first in her family to be able to vote.

“Every time I go into a ballot box, I go for her,’’ Stubbs said. “And every time I vote, I tear up because women’s suffrage and the civil rights movement gave me that right. People died so that I could vote.”

Politics

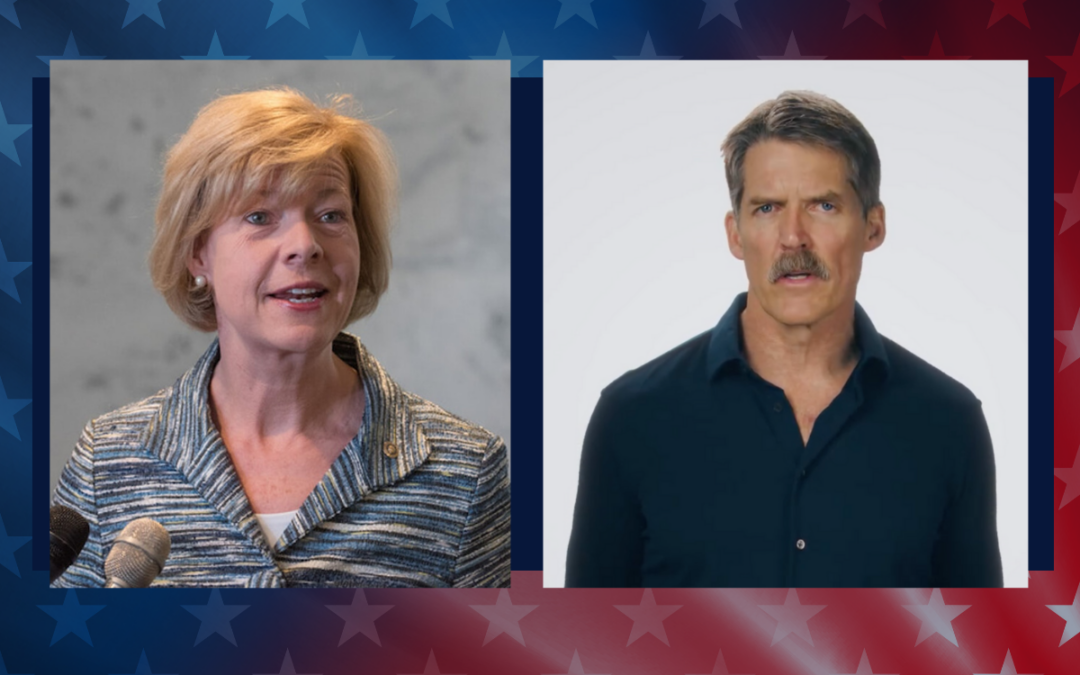

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Who Is Tammy Baldwin?

Getting to know the contenders for this November’s US Senate election. [Editor’s Note: Part of a series that profiles the candidates and issues in...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...