#image_title

#image_title

Farm groups want changes in how markets encourage gluts and low prices, but the Trump administration is unlikely to go along.

Darin Von Ruden doesn’t have to look far to see the myriad challenges Wisconsin farmers face as they struggle to remain in business amid low prices, economic uncertainties, and the coronavirus pandemic that is making already dire agricultural prospects even worse.

As Von Ruden looks out at the rolling hills that make up his organic dairy farm in rural Cashton in western Wisconsin that his family has farmed since the late 1800s, the Wisconsin Farmers Union president can’t help but wonder how much longer he and his family will be able to continue to earn a living there.

Low milk prices for the last five years have driven a record number of dairy farmers — more than 800 last year alone — from the dairy industry. The cost of growing and harvesting grain in recent years has at times been more than the revenue from those crops. While the price of beef, pork and other prices has skyrocketed in grocery stores, farmers increasingly don’t see much of the money for raising those animals.

With each WFU member farmer Von Ruden talks to, he hears new, personalized stories of struggle, more fears about staying viable and not having to leave their property. Without having switched his farm to an organic operation in 2007, Von Ruden questions whether he would have already gone out of business.

“If we wouldn’t have converted, I doubt we would be a dairy right now,” Von Ruden said.

Von Ruden’s son will be the fifth generation of his family to farm the land his ancestors settled more than 120 years ago. But for that operation — and others across the state known as “America’s Dairyland” for the abundance of dairy operations that once dotted its farmscape — to stay in business, major policy and structural changes should occur, Von Ruden said during a recent interview with UpNorthNews.

Federal ag policy under President Donald Trump’s administration has in most cases favored big agribusiness at the expense of small- and mid-size farmers. Trump’s Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue repeatedly has said farmers must get bigger or face the prospect of going out of business.

The administration has enacted other changes, such as loosening grazing restrictions for organic farmers, that have put some smaller organic farmers out of business.

To change that, the leaders of two Wisconsin farm organizations that don’t always agree on policy said the Trump administration’s push for ever-larger farms isn’t a sustainable strategy for the state’s family farmers. Von Ruden and Wisconsin Farm Bureau Federation President Joe Bragger said ag rules must be reworked to create conditions allowing more smaller producers to remain in business.

Chief among changes Von Ruden backs is devising a supply management system that would better protect against a glut of farm products that drive down prices and push many farmers out of business. As farms continue to grow in size and look for ever-greater efficiencies, they produce more and more milk, meat and other products, saturating the market and depressing prices.

To continue to compete in that marketplace, farms grow even more, expanding in an effort to operate more efficiently. That, in turn, drops prices even further. Farmers who can’t afford to borrow enough money to keep growing eventually leave farming.

“We’ve seen it with hogs, chickens, and now dairy,” Von Ruden said. “The idea that you get as big as possible to be as efficient as you can be, and don’t worry about the production end of it, that just doesn’t work for many.”

Farmers have been working for years to maximize efficiencies, Bragger said during a recent interview, but they’re struggling more today than ever before.

“This system of bigger, bigger, bigger all the time, it’s not working for everybody,” said Bragger, who produces milk, chickens and grain on his 800-acre farm in Buffalo County. “Some efficiencies are good, but if we just keep producing more and more, we’ll just keep driving the price down.”

But a supply management system is likely a non-starter with the Trump administration which took direct aim at Canada’s version during trade talks that consistently seek ways to bolster exporting companies rather than the U.S.-based workers or farmers who create the products being exported.

The distribution and processing of farm products also must be changed, the duo said. Currently farmers have too few processors to choose from, a shortcoming made evident when the normal product supply chain was disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic.

Dairy farmers in some cases were dumping milk because they had nowhere to haul it when existing dairies were already full because of decreased demand when schools and businesses shut down to prevent the spread of the virus. Other farmers killed animals because they had nowhere to sell and process them when meatpacking plants were shuttered because of the virus.

“We simply could not get our products into consumers’ hands because we didn’t have enough (processing) plants to do that,” Von Ruden said. “The plants have become too specialized, and there aren’t enough of them.”

Another key to ensuring the survival of farms in Wisconsin’s future, he said, is changing federal agriculture policy to benefit all farmers, not just the largest producers, who receive the biggest share of federal ag subsidies.

Those rules, he said, are aimed at providing food as cheaply as possible. While that idea sounds good on its surface, Von Ruden said, it creates an ever-growing ag industry that benefits agribusiness corporations at the expense of small- and medium-sized farms.

Such policies also tend to promote greater use of chemicals to grow more crops, he said, causing increasing instances of environmental damage in Wisconsin and elsewhere. Much-publicized water-quality issues in Kewaunee County tied to agriculture are among many such concerns that have surfaced across Wisconsin.

Water-quality contamination related to agriculture in Wisconsin threatens drinking water in many communities across the state and often is tied to large farms, otherwise known as concentrated animal food operations, or CAFOs, said Jennifer Giegerich, government affairs director with Wisconsin Conservation Voters.

“If we don’t act to address the water quality concerns in our state, we are endangering our future,” she said.

Among the many challenges related to COVID-19 is at least one bright spot, Von Ruden said. More people seem to have become aware of the fragility of the current food system, composed mainly of a few large providers, he said. In turn, he said, he hears of more people buying food from small butchers, dairies or directly from farmers.

“People are seeing the ties between their food and where it comes from,” Von Ruden said. “If we could get consumers to push the market, we could move toward a system of more providers, making it more possible for more people to make a living growing and processing our food. I think that is something that could help more of us stay in business.”

Politics

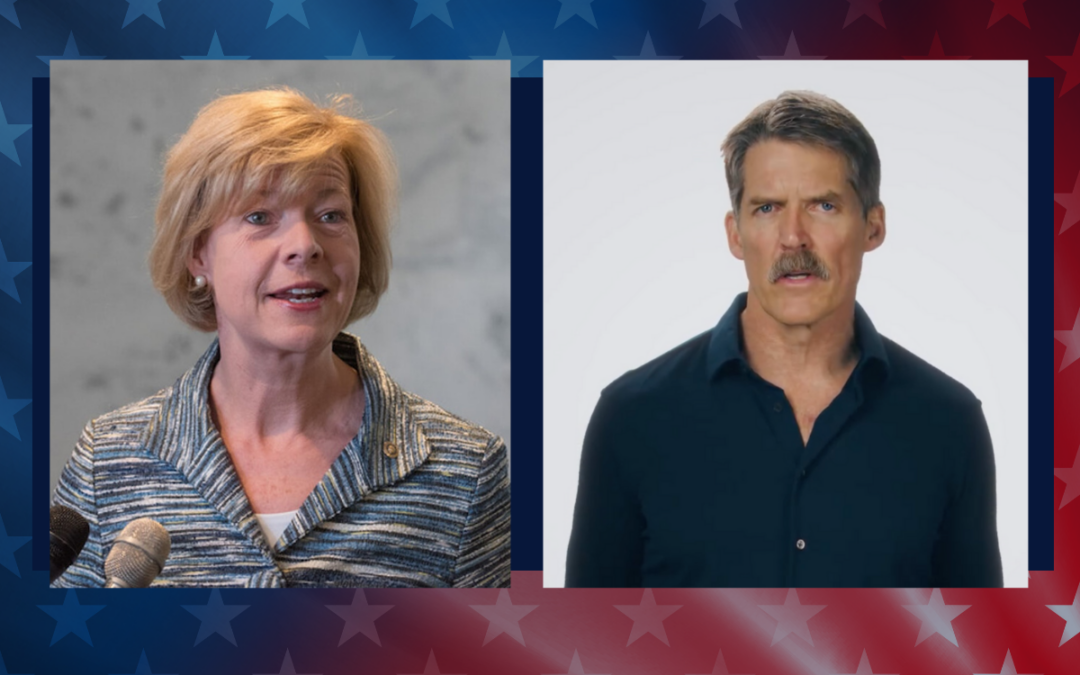

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Who Is Tammy Baldwin?

Getting to know the contenders for this November’s US Senate election. [Editor’s Note: Part of a series that profiles the candidates and issues in...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...