#image_title

#image_title

How racism pervades Wisconsin’s criminal justice system.

Editor’s Note: This story is the first of a three-part series that looks at the disparities faced by African Americans who live in Wisconsin. In most cases, the disparities here are among the worst in the country. Since the killing of George Floyd, rallies that began solely to address systemic racism in policing are now broadening to call for reform in other areas.

Click HERE for Part 2 on health care disparities.

Click HERE for Part 3 on education disparities.

Maya Neal has only met her uncle once, when she was very young. It was years ago, and the now-24-year-old Neal has accepted that she may never see him again.

A repeat offender, Neal’s uncle was arrested and given a prison sentence under Wisconsin’s “three strikes” law from which he may never return.

To Neal, her uncle’s story — and that of so many other people of color throughout Wisconsin — only drives home the underlying racism of the criminal justice system in the state that, according to a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee study, incarcerates Black men at the highest rate in the nation.

“A lot of times people don’t come out of this healed,” said Neal, the political manager for the youth- and young adult-led advocacy group Leaders Igniting Transformation, alluding to calls to focus on rehabilitation over punishment in prisons. “They come out of this worse, or at the least the same as they were.”

Criminal justice disparities represent just one of the many reasons frustrations have boiled over in the country as thousands march each day to protest racism and police brutality following the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, in Minneapolis police custody.

The modern criminal justice system was largely founded on white desires to control African Americans, and inequities have been constant, whether it be the school-to-prison pipeline or racist, community-destabilizing effects of the War on Drugs.

But local African Americans and Black activists are hopeful that the current crop of demonstrations, which are receiving broad national support across racial lines, will have lasting effects similar to those of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Most demonstrations today are calling for reduced or redirected police funding, increased accountability, and training reforms. Redirecting funding for schools, community services, and health care could help reduce crime and violence.

“Those are some of the things that could help immediately, but do we have the political will to get it done?” said Fred Royal, president of the Milwaukee NAACP.

A well-known issue

The first form of policing in the United States dates back to the 1600s, when militia groups known as slave patrols laid a foundation of racism that the law enforcement community has never truly shaken.

For instance, in 1921, police aided a white mob in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that killed as many as 300 Black residents and destroyed over 1,000 homes and businesses.

The massacre took a prominent place recently in the public eye when President Donald Trump picked Tulsa for his first campaign rally in months. It was set for June 19, or Juneteenth, a date that commemorates the end of slavery. Trump bowed to intense criticism and rescheduled the rally.

The federal government admitted over 50 years ago that racism is an issue in policing when the Kerner Commission, which studied unrest in the summer of 1967, concluded that “police have come to symbolize white power, white racism and white oppression. And the fact is that many police do reflect and express those white attitudes.”

Among the commission’s recommendations: increased community program funding, more programs for impoverished areas, and revised police practices to use less force.

“It is a kind of Alice in Wonderland,” the commission’s report reads, “with the same moving picture re-shown over and over again, the same analysis, the same recommendations, and the same inaction.”

The racism identified in policing by the Kerner Commission remains deep-seated to this day, so much so that the FBI has investigated white supremacist infiltration into local police forces as recently as 2015.

The commission’s recommendations — and the overarching inaction — can still be applied today. Programs in Wisconsin have been stripped from communities that need them most, and even schools have been subject to budget cuts to the tune of $4 billion in the last decade alone.

Conversely, police and corrections budgets have risen steadily over the past 40 years as more and more community service responsibilities have been dumped on police departments.

That, coupled with a criminal justice system that stacks the deck against communities of color at every turn through unjust programs such as cash bail, has led to the United States having a quarter of the world’s entire prison population, despite making up just 5 percent of the world’s population.

Wisconsin is among the worst offenders, especially when it comes to racially disparate outcomes.

Keisha Robinson, program director for the Milwaukee Black voter mobilization group Black Leaders Organizing for Communities, or BLOC, is currently experiencing a fight with the bail system.

In October, two of her sons were arrested in connection with a hit-and-run that killed two young girls and injured a young boy in Milwaukee.

Robinson’s then-19-year-old son, Daetwan, was arrested and charged with killing the two girls. Her 16-year-old son, Daecorion, who has no prior record, was accused of spray-painting Daetwan’s car to cover up the hit-and-run.

Daecorion, now 17, was kept in juvenile jail for a few months, Robinson said, until he was formally charged as an adult in January. His bail is $20,000. His public defender requested a lower bail, while prosecutors requested a higher amount. Both motions were denied.

Daetwan’s bail is set at $500,000, and a motion to reduce it to $25,000 was denied.

Robinson acknowledged both sons are accused of serious crimes, but said it is unjust that Daecorion, a teenager with no record, has been held for eight months with a bail the family cannot possibly afford. If convicted, Daecorion could spend up to 10 years in prison due to being charged as an adult.

“We don’t even have a chance at bail,” Robinson said. “…With criminal justice, it’s like there’s no justice. The justice system is just (out) for us.”

Mass incarceration

One of the American Civil Liberties Union’s current flagship efforts is the Smart Justice campaign. It aims to reduce the effects of mass incarceration by reforming the criminal justice system and cutting the prison population in half. One of the top issues for Wisconsin is the state’s probation and parole programs, said Sean Wilson, Smart Justice director for the Wisconsin ACLU.

So-called crimeless revocations can send parolees and probationers to prison for minor technical errors such as borrowing money or missing an appointment. Such revocations of probation or parole terms accounted for more than 3,400, or 37 percent of, Wisconsin’s prison admissions in 2017, according to ACLU analysis.

More than 66,000 Wisconsinites were on parole or probation as of last year, all of them at risk of being incarcerated or reincarcerated on a technicality. More than 39 percent of Black people released from Wisconsin prisons are locked up again within three years, according to the Department of Corrections.

“It has an impact on individuals’ families, it has an impact on individuals’ communities, it has an impact on taxpayers, and it has an impact on our state — the morality of our state,” Wilson said.

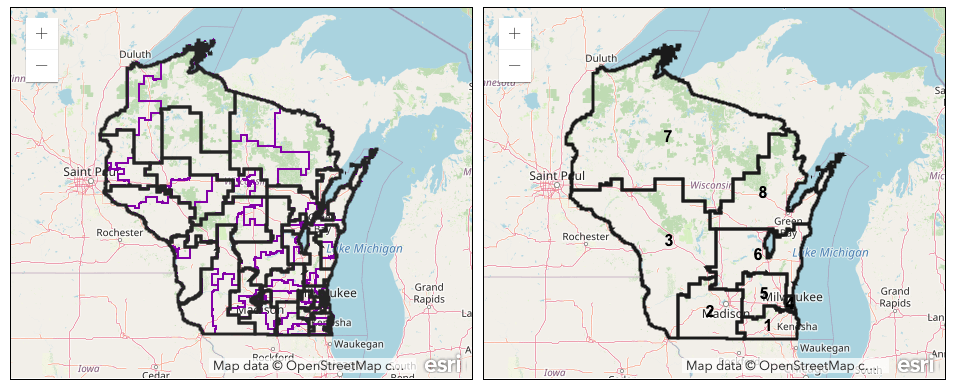

The state’s prison population has increased by over 581 percent from 1978 to 2016, according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics. In 2018, 44 percent of all men in Wisconsin prisons were Black and 23 percent of women were, according to the DOC. That’s despite African Americans only making up a little over 6 percent of the state’s total population.

At the time of the UW-Milwaukee study on mass incarceration, 12.8 percent of Wisconsin’s Black men were incarcerated, nearly double the national average of 6.7 percent. The next-highest rate was Oklahoma, which incarcerated 9.7 percent of its Black men, followed by Iowa and Pennsylvania with a 9.4 percent and 9.1 percent rate, respectively.

In fact, half of Wisconsin’s predominantly Black neighborhoods get their Black population from correctional facilities, a 2016 study found. Black men also receive an average of 19 percent longer prison sentences than white men in similar situations facing the same charges, the federal Sentencing Commission found in 2017.

“I think it’s the idea of us being inherently criminal that fuels the drive behind the treatment in the criminal justice system for Black folks in particular,” said Jamaal Smith, violence prevention manager with the City of Milwaukee Health Department.

He said rhetoric such as Hillary Clinton’s racist and discredited “superpredator” myth and former President Ronald Reagan’s dogwhistle speeches that fueled the War on Drugs did little to help that image.

That same mentality can be seen today, with Trump using racially charged language about “law and order” and advocating for 10-year prison sentences for demonstrators arrested at police brutality protests. Meanwhile, Trump praised white protesters who armed themselves with assault rifles and went to demonstrations aimed at reopening businesses during the coronavirus pandemic.

But socioeconomic factors play a huge role as well.

Poverty, not race, is the largest contributor to crime and violence. In Wisconsin, poverty is a widespread issue for Black residents. The median Black household income in the state in 2017 was about $29,000, less than half that of the median white household income. Nearly a third of Black Wisconsinites live in poverty, compared to about 10 percent of whites.

Mass incarceration is far from the only issue facing Black Wisconsinites. Prison is where a disproportionate amount of Wisconsinites of color end up, but the criminal justice system is made up of more than corrections facilities.

“Reducing the number of people who are in prison in Wisconsin is not going to significantly reduce racial disparities,” Wilson said. “That’s not going to end racial disparities within our criminal legal system. The reason I say that is because (people of color) are at a higher risk of becoming involved in the justice system as a result of them being under police invasion and being at a higher risk for arrest.”

Over-policed and underserved

In the face of rising crime in the 1990s, then-President Bill Clinton signed into law the now-controversial 1994 crime bill — which former Vice President Joe Biden, now the presumptive Democratic nominee, formerly touted as a cornerstone of his Congressional career.

The bill pumped billions into expanding police forces, instituted a federal “three strikes” policy, and expanded the death penalty. It is widely credited with accelerating mass incarceration.

A microcosm of the over-policing problem can be seen in Milwaukee’s Sherman Park neighborhood, where Neal lives. Some rioted in the neighborhood in 2016 after a Milwaukee police officer shot and killed Sylville Smith, a Black man. The officer was charged in the shooting but acquitted.

Since then, police presence has been a near-constant in the neighborhood. It’s ostensibly an effort to repair community trust in the police, but it can have the opposite effect.

“I sit on my porch and I see every day — in the 30-minute time span — five, six, seven police cars just driving by, just patrolling, looking for something to confront and police in my neighborhood,” Neal said. “That’s the impression. That’s what I feel.”

During last year’s budget process, BLOC unsuccessfully lobbied to reduce the Milwaukee Police Department’s budget by $25 million, a request made before the now-familiar calls to defund the police.

BLOC’s request was not without reason: Over 45 percent of Milwaukee’s $638 million general-fund budget for this year went toward the Police Department’s, while a paltry 2.9 percent went to neighborhood services and 2.2 percent went to health services.

That proportional spending is far out of line with other big cities, according to Forbes. New York only spends 8.2 percent of its general fund on its police force, Los Angeles just 25.7 percent, Chicago 39.6 percent. Minneapolis, a similarly sized city to Milwaukee, spends 35.8 percent of its general fund on cops.

Smith, the violence prevention manager, is one of many people beginning to view violence as an issue of public health rather than one of policing. His office developed the Milwaukee Blueprint for Peace, a comprehensive plan that aims to reduce crime in the city while putting resources into community programs instead of continuously pumping money into the Police Department.

“We want safety within our neighborhoods,” Smith said. “We want quality health care; we want quality food options in our neighborhoods. We want the same things that white folks have in their neighborhoods. But then, too, we also do not want to be continuously viewed as being criminals.”

All of the people interviewed for this story said the plethora of problems cannot be solved by one person alone. It will require hard work from every demographic, every department, every advocacy group. But all the ongoing protests feel tangibly different, especially now that a supermajority of the public thinks there is a broader problem in the police than “a few bad apples.”

“When people saw how callous the officer was as he choked the life out of Mr. Floyd, and doing so, so cavalierly, people could actually see the reason why Colin Kaepernick was kneeling in protest of police brutality across this nation,” Royal said. “I think that the message is resonating with a broader audience, which will lend voice in different spaces that haven’t been heard before. I’m hopeful.”

Politics

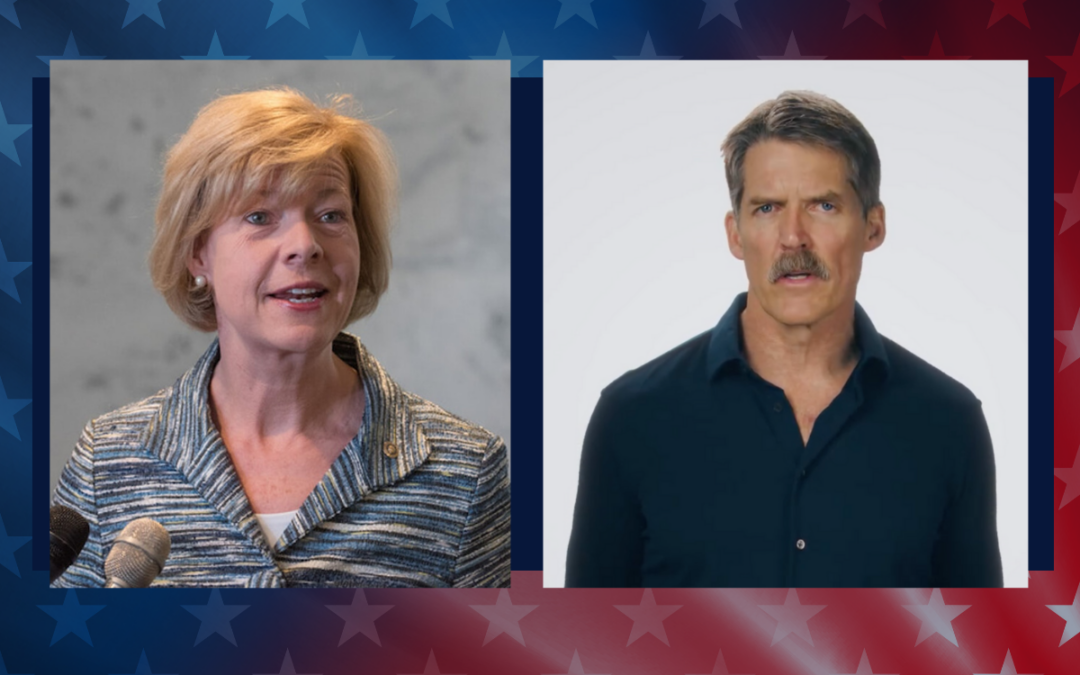

What’s the difference between Eric Hovde and Sen. Tammy Baldwin on the issues?

The Democratic incumbent will point to specific accomplishments while the Republican challenger will outline general concerns he would address....

Who Is Tammy Baldwin?

Getting to know the contenders for this November’s US Senate election. [Editor’s Note: Part of a series that profiles the candidates and issues in...

Local News

Stop and smell these native Wisconsin flowers this Earth Day

Spring has sprung — and here in Wisconsin, the signs are everywhere! From warmer weather and longer days to birds returning to your backyard trees....

Your guide to the 2024 Blue Ox Music Festival in Eau Claire

Eau Claire and art go hand in hand. The city is home to a multitude of sculptures, murals, and music events — including several annual showcases,...